2 April 2012 Edition

Éamonn Ceannt

Remembering the Past

The British were shocked that Éamonn Ceannt’s tiny Irish Volunteers force, including the gravely wounded Cathal Brugha, had held hundreds of British troops at bay

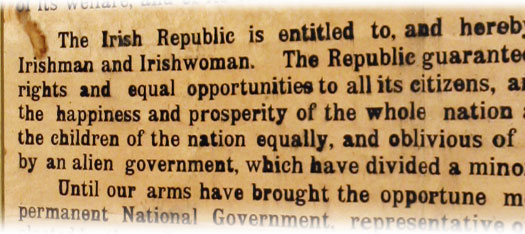

OF THE SEVEN SIGNATORIES of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic at Easter 1916, Éamonn Ceannt is probably the least widely known. Yet he was a pivotal figure in the making of the Rising and a commandant in one of the sectors where some of the fiercest fighting took place.

Ceannt was in command in the South Dublin Union where there were intense fire-fights and hand-to-hand combat between the Volunteers and the British Army. He was more suited to a military role than any of the other members of the Provisional Government of the Republic and the Rising was the culmination of a life of activism dedicated to the achievement of Irish freedom.

That life began in the RIC barracks in Ballymoe, County Galway, on 21 September 1881. Éamonn Ceannt’s father was an RIC officer and was appointed a head constable in 1883. He was transferred to Ardee, County Louth, where Éamonn began his schooling, and later to Dublin, where the family finally settled. Ceannt attended the Christian Brothers School in North Richmond Street. On leaving school he began work as a clerical officer in Dublin Corporation.

The young man’s awareness of Irish nationalism was heightened by the 1798 centenary commemorations in Dublin and by the Boer War, which saw many nationalists using the opportunity to protest against the British Empire. But it was his passion for the Irish language and Irish music which really deepened Ceannt’s political commitment.

Ceannt joined the Central Branch of Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) in 1899. He quickly became fluent in the language and was teaching classes around the country and serving on the national executive. Here he first met Pádraig Pearse and others who would be comrades in arms in the years to come.

While the revival of the Irish language by the Gaelic League is properly recognised as one of the key forces that helped to make the Irish revolution, the revival of Irish music is less often mentioned. Yet it contributed significantly to the national resurgence and Éamonn Ceannt was at the centre of the music revival. He was a founder member of Cumann na bPíobairí (the Pipers’ Club), dedicated to the music of the uilleann pipes and which still thrives today. Ceannt was an accomplished uilleann piper himself and also played the bagpipes, flute and violin.

The first St Patrick’s Day parade was held in Dublin in 1902 on Ceannt’s proposal - it was to promote the Irish language and the second Language Procession in 1903 was even more successful. In that year, Ceannt married Frances Mary O’Brennan. In 1908, he travelled with a group of Irish athletes to Rome where he played the pipes for Pope Pius X.

In 1911, Ceannt was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood by Seán Mac Diarmada. The following year he was writing for Pearse’s short-lived paper, An Barr Bua, and during the 1913 Lock-Out he expressed support for the Dublin workers. With the founding of the Irish Volunteers, Óglaigh na hÉireann, in November 1913, Ceannt really came into his own. He was a natural military leader and contributed greatly to the growth of the movement. He was in command of a section of Volunteers at the Howth gun-running in July 1914. On 9 September, he convened a crucial meeting involving leaders of the IRB, the Volunteers, Citizen Army and Sinn Féin at 25 Parnell Square which agreed to use the opportunity of England’s war with Germany to strike a blow for Irish freedom.

Ceannt was on the IRB’s Military Council, formed in May 1915, to plan an insurrection. He was a signatory of the Proclamation on 17 April 1916 and was placed in command of the South Dublin Union and its outposts. The Volunteers of the Fourth Battallion, Dublin Brigade, assembled at Emerald Square, Dolphin’s Barn, on Easter Monday. Only just over 100 mobilised and Ceannt’s second in command was Cathal Brugha.

The South Dublin Union (now St James’s Hospital) covered a large site and was hugely difficult to defend with such a small number of Volunteers. The British Army soon entered the grounds and fierce fighting ensued. But the Volunteers held out and after the surrender the British were shocked that the tiny force, including the gravely wounded Brugha, had kept hundreds of British troops at bay.

Éamonn Ceannt was court-martialled on the night of 3/4May and executed in Kilmainham on 8 May. In his last statement he wrote:

“Ireland has shown she is a nation. This generation can claim to have raised sons as brave as any that went before. And in the years to come, Ireland will honour those who risked all for her honour at Easter in 1916.”

* Further reading: ‘Supreme Sacrifice - The Story of Éamonn Ceannt’ by William Henry (Mercier, 2005).