25 August 2005 Edition

Remembering the Past - The Lockout

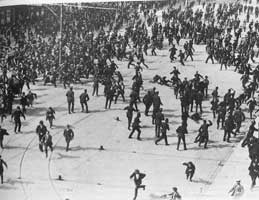

Workers attacked by police during the 1913 Lockout

BY

SHANE Mac THOMÁIS

In 1913, the conditions of Dublin workers were appalling. Nearly 40% of the population lived in tenement slums. The slums were the worst of any city in Europe and 20,108 families were recorded as living in a single room. Infant mortality was the highest in Europe and thousands worked a 70-hour week, for as little as 70p. Women's wages could be as low as 25p.

The Irish Transport and General Workers' Union under 'Big' Jim Larkin rose to 10,000 members by 1913. The bosses too, catching wind of the workers' mood had begun to prepare. They banded together in the Dublin Employers' Federation. Their leader was William Martin Murphy, owner of the Irish Independent Press Group and the Dublin Tramways Company. Murphy decided to use the weapon of starvation to break the spirit of the workers. On 21 August 1913, 200 workers in the parcels office of the Tramway Company received the following notice: "As the directors understand that you are a member of the Irish Transport Union, whose methods are disorganising the trade and business of the city, they do not further require your services.

The parcels traffic will be temporarily suspended. If you are not a member of the union when traffic is resumed, your application for re-employment will be favourably considered."

In response to an affective banning of the Union, a strike was called and on the 26 August, trams around the city stopped and drivers and conductors walked away from them. That evening Larkin addressed the ITGWU tram workers at Liberty Hall: "This is not a strike; it is a lockout of the men who have been tyrannically treated by a most unscrupulous scoundrel. We will demonstrate in O'Connell Street. It is our street as well as William Martin Murphy's. We are fighting for bread and butter. By the living God, if they want war, they can have it."

Larkin had announced that he would speak to a meeting in O'Connell Street on Sunday, 28 August and the meeting was promptly banned but Larkin promised to appear anyway.

Disguised in a heavy beard, he spoke from a balcony window in the Imperial Hotel. owned by William Martin Murphy, before being arrested. The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) then fell on the workers in a vicious baton charge. Men, women and children were felled and beaten as they lay in the street. Hundreds were admitted to hospitals. The brutality was repeated all over the city. James Nolan, a young union member, was beaten so badly that his skull was smashed in. John Byrne also lost his life at the hands of the DMP and Michael Byrne, secretary of the ITGWU in Dún Laoghaire was tortured in a police cell and died shortly after release.

The Catholic Church opposed the workers. Walsh, the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, attacked a plan to send starving children to trade unionists in England, saying; "They can no longer be worthy of the name of Catholic mothers if they so far forget their duty as to send away their little children to be cared for in a strange land."

He also said that it was unacceptable because sending children to comfortable homes with three meals a day would make them discontented with their slum homes when they returned. When strikers' children were taken to the boats and trains, gangs of Christian thugs led by priests attacked them.

As the strike continued pickets were attacked by police and meetings were broken up. Strikers responded with the stoning of trams driven by scabs. Larkin said the workers should arm and defend themselves. This cry was translated into the formation of the Irish Citizen Army which was trained by Captain Jack White DSO, an ex-British Army officer who now fully supported the workers' cause. He later joined the ranks of the anarchist movement during the Spanish Civil War. The ICA was a workers' militia armed with sticks and hurleys, for protection against police and blacklegs.

Some republicans like Tom Clarke, Seán Connolly and the Constance Markievicz, took the side of the workers. But many nationalists refused. Arthur Griffith refused to help because his movement was "national not sectional". He went on the describe the food ships sent by British trade unionists as an "insult". Even the more radical Irish Republican Brotherhood refused to involve itself in a "sectional" dispute.

The camaraderie of trade unionists in Britain was far better, 13,000 went on strike in Birmingham, Sheffield, Crewe and Derby. British workers paid for ships to bring thousands of boxes of food to Dublin and £150,000 was collected.

By the end of the year there had been two meetings between the union and the employers but negotiations were broken off when the employers refused to give any guarantee against victimisation in the re-employment of workers. There were still almost daily picket-line battles between strikers and armed scabs and RIC. Many union members were still being injured and arrested. When 16-year-old Alice Brady was murdered in December angry strikers caught a revolver-carrying scab and beat him to death. Another was thrown into the Liffey. But it was now plain that the union was fighting a losing battle.

By mid-January 1914 a drift back to work had started. A month later there were still 5,000 brave men and women sticking it out in circumstances of the direst poverty. The last group to accept defeat and return to work were the valiant women of Jacobs who held out until mid-March.

Although the ITGWU was not destroyed, it was severely disrupted and financially crippled. But the Lockout had given birth to the Irish Citizen Army and the belief in James Connolly's mind that freedom for the worker could only be won through armed revolution.