10 February 2005 Edition

Fifteen stolen years

BY JOANNE CORCORAN

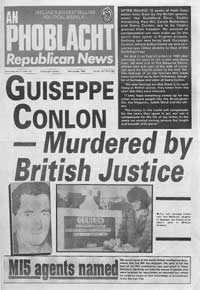

Republicans who remember the story of the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven, as well as the Birmingham Six and countless other British miscarriages of justice, will have seen this week's apology from Tony Blair to the family of Guiseppe Conlon for what it is — too little, too late.

The case of Guiseppe and his son Gerry drove home the corruptness of the British 'justice' system. Guiseppe was arrested as part of a group of unfortunate Irish people who became known as the Maguire Seven, after his son had been picked up as part of the Guildford Four. Guiseppe languished in a British jail for five years before dying in 1980. He, like all those arrested for the 1974 bombings, was innocent. After the massive suffering inflicted on the Conlon family, an apology from the establishment that put them through it must seem hollow indeed.

It's probably amazing for republicans who witnessed the case to think that a whole new generation's only knowledge of the Guildford Four stems from Jim Sheridan's movie, In the Name of the Father. While a worthy film, like all cinematic escapades into Irish history, it falls victim to dramatisation, liberal interpretations of the truth, and of course doesn't come close to telling the whole story of what was happening during that period.

Here, An Phoblacht recalls the cases of the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven.

By any means necessary

During the latter half of 1974, the IRA organised an intensive bombing campaign in London and southeast England.

On 5 October, bombs were placed in two pubs in Guildford, the Horse & Groom and the Seven Stars. Both were popular with local Guards recruits. The Horse & Groom bomb exploded at 8.30pm, killing five people. The Seven Stars landlord immediately cleared his pub and there were no casualties there.

One month later, on 7 November, a bomb was hurled into the King's Arms in Woolwich, opposite the Royal Artillery depot. Two people were killed.

Later that month, two bombs were placed in Birmingham city centre pubs, killing 21 in total.

The reactions to the bombings unleashed a latent anti-Irish feeling across Britain.

Irish community centres were an inevitable target for petrol-bombing. Less inevitable a target, perhaps, was a Roman Catholic junior school in Birmingham, also attacked.

The anti-Irish hysteria turned up in parliament. The Home Secretary introduced the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Bill (PTA), within a week of the Birmingham bombings. The Bill made membership of and support for the IRA an offence and empowered the police to arrest without warrant anyone they suspected of being concerned in 'terrorism', but against whom they had not assembled sufficient evidence in regard to a specific offence.

The British establishment wanted to get the perpetrators of the bombing campaign by whatever means necessary. This contrasted with the reaction of the Dublin Government to the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of 1972 and 1974, in which the British state was involved. The Dublin Government had swept those bombings under the carpet, though it still managed to use them to introduce the Offences Against the State Act in '72 and endorse it in '74, a law primarily aimed at curtailing the IRA.

Arrests

The first person arrested under the PTA was Belfast man Paul Hill, who lived in a squat in Kilburn in North London. On 30 November his friend from Belfast, Gerard Conlon, who had spent some time in England in October 1974, was arrested at the family home in Cyprus Street, Belfast, and taken to Springfield Road RUC Barracks. From there he was flown to England and taken to Guildford police station.

Both men were accused of the Guilford bombings and within a day the Surrey police had obtained confessions from them. These confessions were the basis of the men's prosecution, but it was later revealed in court that the men had been tortured and beaten into signing them.

In them, they listed friends and relatives and the police had their excuse to round up a large number of other 'suspects'. Among these were Patrick Armstrong, another lad from Belfast, and his English girlfriend, Carole Richardson.

Hill and Conlon were also forced to provide addresses of what were supposed to be two bomb factories. One of these was that of Conlon's aunt, Annie Maguire.

Trial

The trial of Hill, Conlon, Armstrong and Richardson opened at the Old Bailey on 16 September 1975.

In court, police didn't reveal what had prompted their interest in Hill, saying simply that they were acting on 'information received'. Subsequently, it was revealed that a known Belfast grass had been paid for his name.

The lack of evidence against him and the others was astounding.

Artist's sketches of the people suspected of planting the bombs looked nothing like any of the four.

Eight witnesses failed to pick out Carole Richardson in an identity parade. None of the others was ever put in one.

Consequently, there was no material witness evidence against the four accused; nor was there any forensic evidence. The prosecution case rested squarely on the four confessions. However, all four defendants entirely repudiated these statements and maintained that they were made under duress.

Hill had actually been driven past the Horse & Groom and told by one policeman:

"That's the pub you blew up." At the police station, as a result, both of the violence he suffered — he mentioned a gun being held to his head — and of threats against his girlfriend, who was pregnant with their child at the time, he signed statements put in front of him, which were full confessions to both bombings.

Armstrong and Richardson were both beaten. Conlon had been slapped in the kidneys and testicles, and threats had been made against his family.

The interrogation of Richardson, only 17 at the time, breached judge's rules in that no parent, guardian or legal representative was present.

In addition, Richardson, Hill and Armstrong all had alibis.

On 20 December 1974, Richardson's friend, Frank Johnson, walked into a police station and told them he had been with her the night of the bombing. He, Carole and another girl had gone to a concert and he even had photographs of the three with the band that played, 'Jack the Lad'.

The police challenged Johnson's memory, but his favourite football team, Carlisle United, had beaten Chelsea that day, and he could remember it very clearly. Johnson was then taken into police custody and told that if he insisted he was with Richardson, then he must have been involved in the bombings, because she had signed a confession saying she did it.

Statements from the second girl and the band were dismissed. A few weeks later, Johnson was taken back into custody and subjected to brutal treatment for three days until he amended his statement. His new statement only just gave Richardson time to be involved in the bombings.

At the trial, Johnson reverted to his original statement and told how he had been treated, however the jury disregarded his evidence and that of the other alibi witnesses.

Guilty

When reaching their verdicts, the jurors rejected the unexplained aspects of the trial. The judge made it perfectly clear to the four young people that, had capital punishment been in force, they "would have been executed".

The trial ended on 22 October. All four were found guilty of their individual charges.

The sentences were noteworthy for being the longest ever handed down in an English court of law, and were entered in the Guinness Book of Records. The quartet all got life, but Justice Donaldson used his judicial discretion to make recommendations of minimum terms. He said Richardson should serve at least 20 years, Conlon not less than 30, and Armstrong not less than 35.

He was at his most draconian, however, when addressing 21-year-old Paul Hill: "In my view your crime is such that life imprisonment must mean life. If as an act of mercy you are ever to be released it could only be on account of great age or infirmity."

Appeal

After the Balcombe Street trial, when four IRA men revealed that they had actually been responsible for the Guildford and Woolwich bombings, the Guildford Four launched an appeal.

This opened on 10 October 1977 before Lord Justice Roskill, Lord Justice Lawton and Mr Justice Boreham.

IRA men Joseph O'Connell, Harry Duggan and Eddie Butler, three of the prisoners known as the Balcombe Street Four, and Brendan Dowd, arrested a year previously, all gave evidence in person.

The thinness of the prosecution case could scarcely be concealed, but, on 28 October, the appeals were dismissed.

"We are all of the clear opinion that there are no possible grounds for doubting the justice of any of these four convictions or for ordering new trials," stated Roskill.

The crucial factor enabling the judges to reach their decision was Brendan Dowd's evidence. By pinpointing tiny disparities between his testimony, such as his failure to remember whether a car he had stolen was a Ford Escort, Cortina or Corsair, and that of the other three, who claimed responsibility for the bombings, the judges argued that the appeals were without merit.

Roskill noted that O'Connell, having already been convicted of six killings, "had nothing to lose by accepting responsibility for a further seven".

Wasted years

It was to be 12 more years before the Guildford Four wound up in court again. In the interim, their families and solicitors, and various human rights groups, had been lobbying intensively for their release. An appeal had been due in January 1990, however the British Government itself decided to re-open the case on 19 October 1989, an exercise in damage limitation. It had become increasingly obvious to the public, through the work of the four's supporters, that the conspiracy that led to them being framed involved various leading figures in the legal profession and the police. No doubt it was hoped that a 'small scandal' in 1989 would prevent a bigger scandal later on.

The new investigation into the case was carried out by Avon and Somerset Police. Roy Amlott QC, speaking in court, said that the new evidence "has thrown such doubt on the honesty and integrity of a number of Surrey police officers investigating this case... the Crown is now unable to say that the convictions of any of the four were safe or satisfactory". Lord Lane, the Lord Chief Justice, concurred with the QC's assessment and overturned the convictions against the four.

Three of the police officers who conducted the original interviews were subsequently suspended by Surrey police. Two others left the force.

The release of the four didn't signify any change of heart by the British state. Despite having quashed the convictions, the establishment still wouldn't admit their innocence.

And of course, there was an ulterior motive for their release. Freeing the Guildford Four had the immediate political impact of strengthening the Anglo-Irish Agreement, making it easier for Britain to have people extradited from the 26 Counties. The Dublin Government went along with this, and also hopped on the bandwagon of the Guildford Four's release, despite having done nothing to help their case.

Attention immediately shifted to the case of the Birmingham Six, jailed in similar circumstances in the same period.

The Maguire Seven

Annie Maguire lived with her husband Paddy and their three sons — Vincent, John and Patrick, her daughter, Anne-Marie and her brother, Seán Smyth in North London.

Shortly after her nephew Gerry was arrested, they were visited by his father, Guiseppe Conlon.

During the 1970s, Guiseppe suffered a range of illnesses, including pulmonary tuberculosis. He rarely left his home, but when Gerry was arrested he went to England to help.

Unable to visit Gerry that day, Guiseppe went for a drink with some of the family and a friend, Pat O'Neill. Annie was minding his three children while his wife was in hospital awaiting their fourth child.

At 8.45pm, the police rang her doorbell. Not knowing what was going on, Annie and her children were taken to Harrow Road police station. Down at the local pub, Paddy, Guiseppe, Pat and Séan were picked up. The Maguire youngsters were released, but the others were taken to Guildford and held on remand.

The four men were charged with possession of explosives. Annie Maguire was charged with murder in connection with the Guildford and Woolwich bombing offences. She had a watertight alibi for the evening when the Guildford bombs had exploded and because she refused to be bullied into a forced confession, there wasn't a scrap of admissable evidence against her. The murder charge was later dropped, but she was still remanded on a charge of possessing explosives. Her children, Vincent (16) and Patrick (13), were taken back into custody and similarly charged. They were both sent to a juvenile remand home.

The trial of the seven started the day after the Guildford Four's.

Despite no obvious evidence, the prosecution capitalised on the hysteria of the time and managed to convict Annie Maguire (she served ten years), Paddy Maguire (served ten years), Patrick Maguire (served four years), Vincent Maguire (served five years), Seán Smyth (served ten years), Guiseppe Conlon (sentenced to 12 years, died in 1980), and Patrick O'Neill (served eight years). While Conlon had long been ill, nobody doubted the impact five years in jail had had on an innocent man.

It wasn't until 1991 that all seven convictions were overturned.

The Balcombe Street Four

On 12 December 1975, Joseph O'Connell, Harry Duggan, Hugh Doherty and Eddie Butler were arrested in London at the conclusion of what has become known as the Balcombe Street siege. After a dramatic car chase through the West End the previous Saturday, the four had taken refuge in 22b Balcombe Street, London.

After the siege ended, the four gave their names to the police and added that they were all IRA Volunteers.

It soon became apparent that the police had captured the Active Service Unit (ASU) responsible for the intensive bombing campaign conducted since August 1974. The problem was that they had already jailed people for the Guildford and Woolwich bombs.

In May 1976, O'Connell, Butler and Duggan got in touch with the Guildford Four's solicitor, Alexander Logan, and agreed to make statements about Guildford and Woolwich, along with another republican prisoner, Brendan Dowd, who had been arrested a year earlier.

The Balcombe Street Four came to trial at the Old Bailey on 24 January 1977.

There were exactly 100 indictments, but there was no reference to the Guildford bombings.

In normal circumstances, IRA defendants would have refused to recognise the court, but the men opted to make a statement dealing with the Guildford and Woolwich bombings.

O'Connell made a passionate speech which lifted the lid on British 'justice', then he and the others were led from the dock. The jury acquitted the defendants on 26 of the 100 indictments against them. The trial was considered a hollow victory for the prosecution, because the defendants had managed to demonstrate falsehoods in its case. However, nothing else was said about the Guildford and Woolwich bombings, after the prosecution claimed it was a conspiracy to have those already serving time released.

Each of the four men received a 30-year minimum sentence.

They were eventually released in 1999, after 23 years, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.