17 June 2004 Edition

Death of Eileen Howell

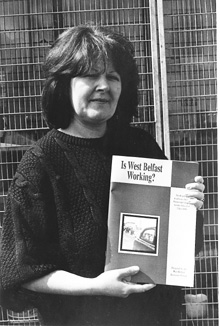

Eileen Howell

Life in its most beautiful form, the birth of a new baby, can also at times be at its most cruel.

That is how I, and I am sure the Howell and Duffy families, feel after burying Eileen Howell last Tuesday morning, two weeks after the birth of her first grandson, a child she had looked forward to arriving so much. But her debilitating illness prevented her from nursing the child as she lay in her intensive care bed in the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Mercifully, she regained consciousness for a short period and saw him on a video taking his first breaths of life.

I cannot believe I am sitting at a computer trying to write a tribute to Eileen, who I've known for 25 years, who I spoke to in the Falls Community Council offices just over a month ago and who was, as a partner to Ted, a mother to Eamon and Proinsias, and a sister, a tower of strength in a quiet and unassuming way.

There are times when life doesn't make sense, when its natural rhythm has been knocked off course, when one can't dwell too long for an answer to the ponderous question 'why?', because it opens up the truly appaling vista that is death and in Eileen's case, unexpected death at an age with so much yet to give.

For the family, friends and comrades of Eileen, this is one of those times.

There is no satisfactory emotional answer to the question why Eileen should be no longer with us. There is of course a biological answer, which explains the speed with which her body was overcome by cancer but on this occasion that is insufficient to deal with the "great loss" to us all as Tom Hartley described the impact of Eileen's death at her graveside.

It is difficult to write about Eileen without reference to Ted, because to me it was always Ted and Eileen.

They had an old fashioned relationship, which took root in the midst of war in the early '70s. The pattern of times to come was set early on. On their wedding night Ted was arrested and narrowly escaped internment when he was released the following morning on false identification papers. Prison or detention for Ted was a constant companion for Eileen in the early years of their marriage.

They met as teenagers. In Ted's Irish News insertion he described their time together as "38 years of memories and inspiration to fuel the rest of my life". It was a partnership before the modern times of equality, before the use of the word 'partner' to describe one's husband or wife.

I first met Eileen in the late '70s, when she and Ted lived in a two-up two-down in Iveagh. With Ted deeply involved in the struggle for freedom, Eileen, in the words of Gerry Adams at her graveside, 'built a home' for them and their two boys.

And while doing so, she started out on an educational journey, which would see her achieving a degree in Social Policy. Adult education, commonplace nowadays, was rare back then, especially for a young woman whose partner was a leading republican, seldom at home.

But that was Eileen's trademark, breaking new ground, not to the sound of trumpets, not with a fanfare, but with quiet determination. Danny Morrison, a lifelong friend, recalled that Eileen set up in the mid-'70s the first ever crèche he knew of for the families of prisoners, above the centre in Linden Street where the families got the bus to Long Kesh.

Looking back to those years, I would say Eileen was the first "professional" republican I met. Her educational training encouraged her to rely on irrefutable facts and figures to reinforce her arguments.

Eileen didn't recognise boundaries. There were state imposed glass ceilings everywhere for Catholics, for nationalists, for women, but she didn't allow them to restrict her or her ambitions.

She had a fine mind, well honed by education. She used this talented mind in an ambitious way. She had plans above her station, as her opponents would have said.

But the plans were not for her personal advancement. She could have easily joined the elite, the people with power. But that wasn't Eileen's way. She was on the side of the powerless; those discriminated against, those on the margins without a voice.

Eileen was more comfortable challenging those with the power. She was at home pressurising those with the resources to hand them over to improve the lot of working class people.

Her beloved Falls Community Council is an institutional landmark of what Eileen stood for. Under one roof, on the main Falls Road, in the heartland of the freedom struggle, stands an impressive, dynamic entity, employing pioneers demanding change, a permanent reminder of Eileen's work.

In every sense of the meaning, she was a self-made woman.

Ray Bassett, joint Irish Chairperson of the Irish-British Secretariat, said of Eileen at her funeral that she had "a gentle nature but was very, very persistent in getting what she was after".

At her funeral Mass, the priest correctly said: "She travelled the world knocking doors. She had a passionate belief in creating opportunities for the less well off."

So it was only fitting that Deirdre McAliskey, in a beautiful, haunting voice, ended the funeral mass with the inspirational song, Bread and Roses.

It was well chosen because the lyrics reflected Eileen's own outlook. She was about improving people's lives now, while we struggle for our country's freedom.

Eileen was a generous soul and a great hostess. She liked nothing better than being surrounded by her friends, a good glass of wine and great food cooked by Ted and a yarn into the early hours of the morning. An invitation to dinner at Ted and Eileen's meant a certain treat.

My treasured memories will be the Christmas visits made by Tom and myself to their house every year since I got out of jail in 1988. It was our first port of call 'doing our rounds'. We were greeted at the door with smiles and hugs and we left 'four sheets to the wind', as they say here, with smiles on our faces and 'fuel' in our veins.

Dúirt Gerry Adams freisin "go bhfuil lá brónach, lá dorcha in ár shaol.. go bhuil croí Ted briste". And he is right; these are sad and dark days and Ted's heart is broken and their family and friends are at a loss as to what to do or how to make sense out of it all.

But sense will be made of it in the fullness of time. And as we go along we will pick up the pieces again. As Gerry Adams said, we will do what Eileen would have done. We will go on doing what we have done all our lives. Until then, we will draw off our memories of Eileen at the point where she touched us.

As we left the cemetery, we were helped on our way by Tom's explanation of 'Port na bPúcaí', the lament for the dead played at Eileen's mass.

It is about those who go before us. They leave an echo or a footstep for us to follow and in Eileen's case she will be step by step with us in the times ahead, whatever the challenge.

BY JIM GIBNEY