2 October 2017 Edition

October 1917 – The rebirth of Sinn Féin

Remembering the Past

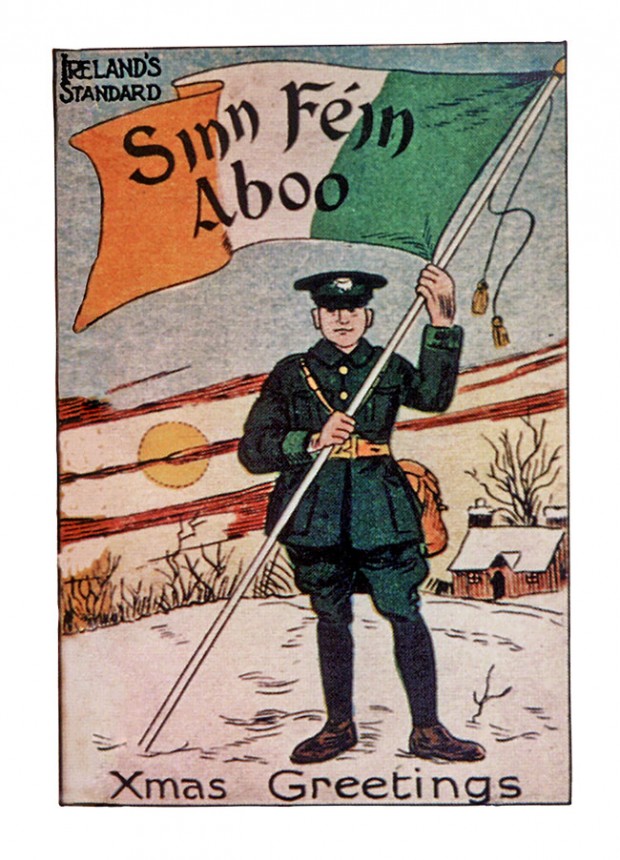

By mid-1917, with a huge influx of members, Sinn Féin clubs were appearing across the country

By Aengus Ó Snodaigh TD & Mícheál Mac Donncha

DUBLIN’S Mansion House, Teach an Ardmhéara, has been the scene of many historic meetings. One of the most important was the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis of 1917 which adopted a republican constitution for the first time.

Many who were called Sinn Féiners in 1917 were not actually part of the Sinn Féin organisation but were in fact members of one of the many other nationalist or republican groups spreading across the country. But the name Sinn Féin carried weight for two reasons.

Firstly, up to 1916, it had been a common label for all nationalists who were more radical than the Home Rule Party. Secondly, this led to the 1916 Rising being called by the press and by much of the general public “The Sinn Féin Rebellion”. The organisation as such was not directly involved in the Rising, though many of its members were.

Prior to the Rising, Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin was floundering but, by mid-1917, with a huge influx of members, Sinn Féin clubs were appearing across the country. Such were their numbers that the affiliation fees allowed for the maintenance of a head office at 6 Harcourt Street in Dublin and for two paid organisers to take to the roads.

In the main, the members ignored or rejected the original stated aim of Arthur Griffith for a “dual monarchy” (i.e. maintaining the link with England through the crown but with an independent Irish parliament). The Rising had brought the demand for an Irish Republic to the fore.

The Liberty Clubs suggested by Count Plunkett after his by-election victory in February 1917 were also expanding rapidly. They were at a disadvantage, not having the false reputation of having organised the 1916 Rising or having a central office.

The Irish Volunteers were also growing at a pace but were antagonistic to Arthur Griffith’s dual-monarchy proposals.

A Mansion House Committee had been set up in April 1917 to pursue the unification of all republicans under the one banner and held a meeting in early June 1917. Representatives of the Liberty Clubs and Sinn Féin (including Cathal Brugha, Thomas Dillon, Count Plunkett, Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, Rory O’Connor and some others) were there to attempt to prevent further fractures and to move towards unification. The meeting was held in Cathal Brugha’s house in Rathmines and was hot and heavy.

It was suggested to Griffith that he hand over Sinn Féin to the Volunteers but Griffith was having none of it.

“Sinn Féin will not give up its name,” Griffith said. “I was elected president by a convention of Sinn Féin and I can only give over the presidency to somebody elected by another convention.”

Nearing the end of the debate (the last tram would be passing soon) Thomas Dillon said that the alternatives open were to found a new organisation or take over Sinn Féin on conditions to which Arthur Griffith agreed.

Dillon recalls Cathal Brugha asking: “Which do you think we should do?”

Dillon replied: “The obvious and simplest course.”

Brugha then said: “That’s what well do.”

Griffith agreed to put the suggestion to the Sinn Féin National Council that half of them would stand aside to allow on six representatives from the Liberty Clubs and the Mansion House Committee. Thomas Dillon was to become joint honorary secretary while the president and paid officials would remain until the next Sinn Féin convention.

Sinn Féin accepted the proposals shortly afterwards.

The friction was still very close to the surface, however, and nearly boiled over during the Kilkenny by-election at the end of July, with one group proposing to stand Eoin Mac Néill and another opposing him because of his countermanding order on Easter Sunday 1916. Eventually, William Cosgrave – a longtime Sinn Féin member, a Volunteer officer and a recently-released prisoner – was nominated. Cosgrave won the election with a two-to-one majority.

In August, preparations began for a Sinn Féin convention to be held in October. It was now called an Ard Fheis. Apart from electing a new officer board, the main focus of the Ard Fheis would be to pass a new constitution for the party.

The move away from Arthur Griffith’s dual monarchy towards republican principles was to cause much acrimonious debate between Griffith and Brugha especially. At one stage, the republicans walked out, with Éamon de Valera succeeding in bringing them back and agreeing a compromise.

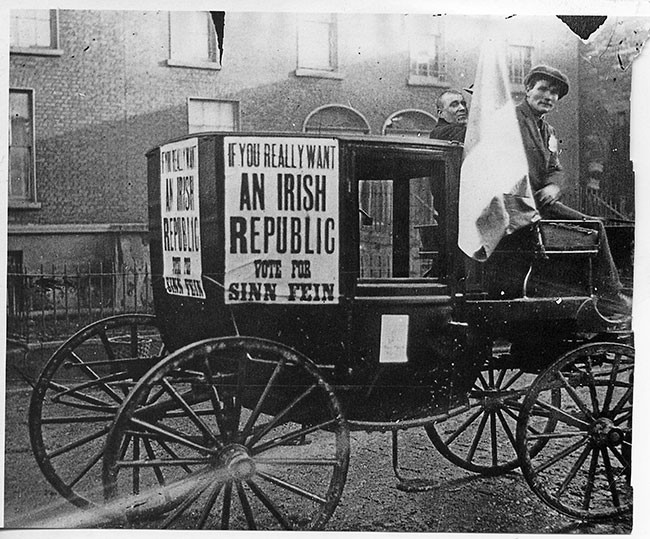

Arthur Griffith chaired the Ard Fheis when it met on 25 October and gave a report on the state of the organisation. There were 3,300 clubs representing more than 250,000 members and 1,700 delegates from 1,000 clubs. Sinn Féin was also financially sound, with £1,272 to its credit.

He then gave a short history of Sinn Féin from the beginning and said that without the sacrifice of 1916 the organisation would not have been as strong as it was. Cathal Brugha then proposed the changes to the Sinn Féin Constitution, which were carried without discussion. The key section was the wording proposed by de Valera, presented as a compromise but clearly republican:

“Sinn Féin aims at securing the international recognition of Ireland as an independent Irish Republic. Having achieved that status, the Irish people may by referendum freely choose their own form of government.”

The Constitution also stated that Sinn Féin, in the same of the sovereign Irish people, shall:

“Deny the right and oppose the will of the British Parliament and British Crown or any other foreign government to legislate for Ireland.

“Make use of any and every means available to render impotent the power of England to hold Ireland in subjection by military force or otherwise.”

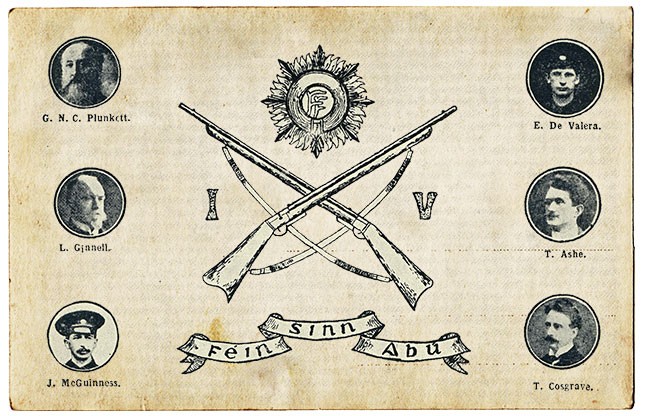

The next item on the clár was the election. Both Arthur Griffith and Count Plunkett stood down in favour of Éamon de Valera in the presidential race. The Dublin Castle authorities had considered suppressing the Ard Fheis but allowed it to go ahead in the belief that, with three candidates for the presidency, the organisation would split.

Arthur Griffith and Fr Michael O’Flanagan were elected vice-presidents, W. T. Cosgrave and Laurence Ginnell were elected honorary treasurers, and Austin Stack and Darrell Figgis became honorary secretaries.

A council of 24 was elected which bore very little resemblance to the old Sinn Féin.

Constance Markievicz failed in her attempt to prevent Eoin Mac Néill from being elected (in fact, he topped the poll).

The members of the new Council of Sinn Féin were: Eoin Mac Néill, Cathal Brugha, Michael Collins, Ernest Blythe, Richard Hayes, Fionán Lynch, Seán Milroy, Constance Markievicz, Count Plunkett, Piaras Beaslaí, Joseph McGuinness, Harry Boland, Kathleen Lynn, J. J. Walsh, Fr Matt Ryan, Joseph McDonagh, Fr Wall, Mrs Thomas Clarke, Diarmuid Lynch, David Kent, Dr T. Dillon, Mrs Joseph Plunkett and Seán MacEntee.

In his acceptance speech, de Valera made it clear where he stood:

“We say it is necessary to be united under the flag under which we are going to fight for freedom – the flag of the Irish Republic. We have nailed that flag to the mast; we shall never lower it.”

Thomas Dillon wrote that Arthur Griffith remained a monarchist, believing that a monarchy on Scandinavian lines would be better than a republic, and that Griffith accepted the new constitution perhaps because of the respect he had developed for de Valera. Of course, the new Sinn Féin had risen on a tide of post-1916 republicanism and Griffith was in no position to hold it back. But his non-republicanism, and that of his followers, remained, albeit below the surface in Sinn Féin. As Fr O’Flanagan later stated, division re-emerged when Griffith brought back the Treaty from London in 1921.

But that was all in the unfathomable future.

One hundred years ago this month, in October 1917, hopes were brighter than ever as Sinn Féin embarked on its new mission to achieve the Irish Republic.