1 December 2016 Edition

A flaming inspiration – The Armagh women POWs’ hunger strike

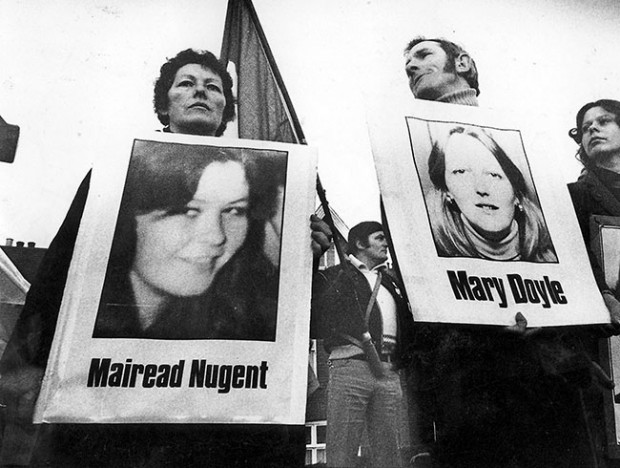

• Republicans came onto the streets in 1980 to back the Armagh hunger strikers

Far from being a mere solidarity action in support of their male comrades, the Armagh women’s hunger strike was a unique event loaded with strategic and symbolic importance

1 December marks 36 years since the commencement of the hunger strike by three Armagh women republican prisoners for the restoration of political status

TOO OFTEN, the anti-criminalisation protest campaign which took place in Armagh Gaol stands in the shadow of the H-Block protests and the actions of female republican prisoners are misrepresented as a mere extension of the actions of their male comrades. The Armagh women, though, undertook their protest campaign in their own right, exercising their own agency in order to assert their own identity as political prisoners.

Far from being a mere solidarity action in support of their male comrades, the Armagh women’s hunger strike was itself a unique event loaded with strategic and symbolic importance.

From the very beginning of the prison saga and the introduction of the criminalisation policy in 1976, republican POWs in the women’s prison at Armagh resisted British attempts to label them and their cause as “criminal”. Like their male comrades, they protested using the only weapons at their disposal – their own bodies.

Since all women prisoners in the North were permitted to wear their own clothing, the Armagh women did not engage in a Blanket Protest. They did, however, resist criminalisation from the start by means of a no-work and non-co-operation protest. The women refused to carry out prison work or to acknowledge the authority of the prison staff. They observed their own command structure, known as “A Company, IRA”, and maintained military discipline in the gaol.

On 7 February 1980, male prison warders were brought into Armagh from Long Kesh, ostensibly to help carry out a search of the women’s cells. Their true mission was to brutalise and intimidate the women and several prisoners were injured in the violent clashes which took place that day.

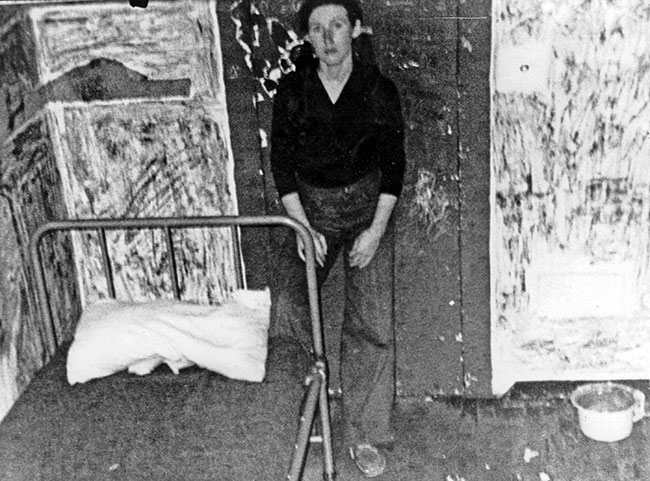

When the ‘search’ was finally over, the women were locked in their cells and denied access to the bathrooms. After the women were released from their cells the following day, the bathrooms remained locked. The women saw no choice but to embark upon a no-wash protest, spreading the contents of their overflowing chamber pots over their cell walls and refusing to bathe for more than a year.

The no-wash protest was naturally very difficult for the prisoners but their conviction was strong. As far as they were concerned, the filth of excrement, urine and menstrual blood was far less repulsive than the cruel label of “criminal”.

• Mairéad Farrell in her cell during the no-wash protest

When planning began for the 1980 Hunger Strike, the prisoners in Armagh declared their resolve to take part. The republican leadership on the outside, however, tried to discourage the women from joining the fast. In fact, the leadership on the outside did not want a hunger strike to take place at all. Even once the leaders had agreed to support the men’s strike, they remained reluctant to allow the women to participate. They even sent information into Armagh about the detrimental impacts of prolonged fasting on the human body.

The leadership worried that a fast in Armagh would divert attention away from the H-Blocks and over-extend the resources of the Republican Movement. They were also concerned that biological and psychological factors would make a women’s hunger strike more susceptible to defeat.

The women themselves were initially uncertain about whether they could sustain a hunger strike.

They were few in number (only 28 compared to hundreds in the H-Blocks), and the no-wash protest and poor conditions had already taken their toll on the prisoners’ health.

These concerns were outweighed, however, by the women’s belief in the strategic value of a cross-prison strike which would overstretch the resources and will of the authorities.

The involvement of women in the strike would also clarify that the true issue at the heart of the protest was the criminalisation policy, and not merely the desire of prisoners to wear civilian clothing. The risk of female prisoners dying on the strike would also place additional moral pressure on the authorities and increase support in the community.

The women were determined to take part.

Ultimately, it was agreed that female prisoners in Armagh would commence a hunger strike approximately one month after the men in Long Kesh. This would allow their entry to coincide with the weakening condition of the men in order to place maximum pressure on the authorities.

The Armagh women’s decision was announced on 22 November, and An Phoblacht/Republican News was quick to clarify that this decision was “not a solidarity action with the seven H-Block hunger-strikers, nor a limited token gesture” but was being taken “in their own right to political status”.

It then fell to O/C Mairéad Farrell and Adjutant Síle Darragh to agree Armagh’s hunger strikers. They spoke to each woman who had volunteered, ensuring that she understood the potential impact a hunger strike would have upon herself, her comrades and her family.

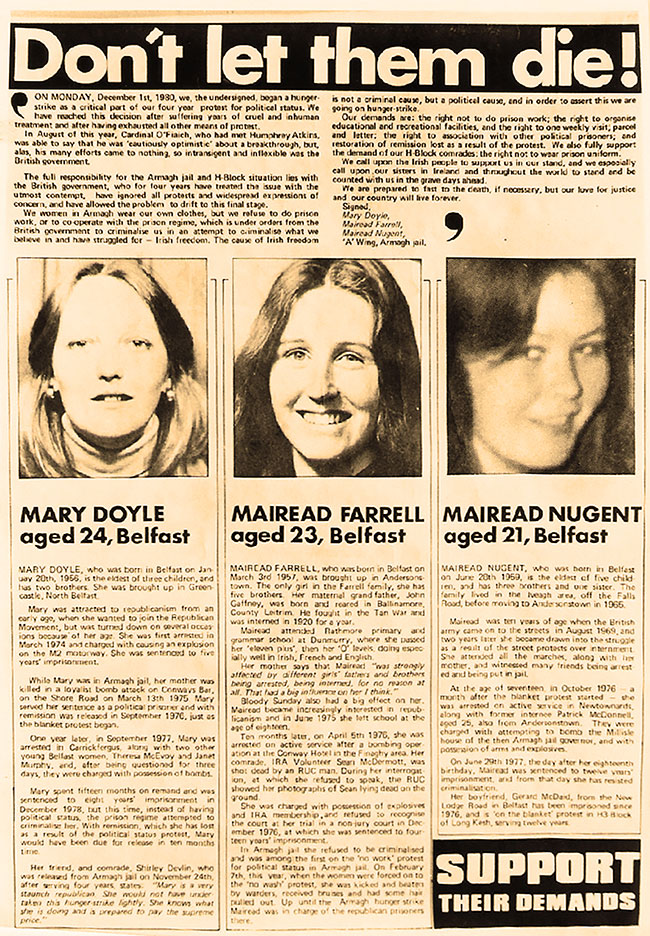

• The Armagh hunger strikers: Mairéad Farrell, Mairéad Nugent and Mary Doyle

After careful deliberation by the two leaders, three women were chosen to embark on the fast: Mairéad Nugent (aged 21), Mary Doyle (aged 24), and Mairéad Farrell herself (aged 23). Additional volunteers were selected as ‘back-ups’ to take the place of one of the initial three in the event of her death.

The trio commenced their fast on 1 December 1980.

In their official statement, they declared:

“We are prepared to fast to the death, if necessary, but our love for justice and our country will live forever.”

The three were immediately moved to share a double cell and were advised to drink eight pints of water per day, with salt. Mary Doyle remembers being “sick as a dog” on that first night. She also recalls the constant efforts of the prison warders to torment the hunger strikers, ensuring that their cell was never without food. Plates of steaming hot chips replaced the barely edible slop which the women were usually served.

Warders also delivered hate mail from the outside and shouted abuse at the hunger strikers. Mairéad Farrell recalled one of them shouting: “Why don’t you hurry up and die, you bastards?” In the face of such torment, the women drew comfort and strength from their comrades and the firm belief in the justice of their cause.

The authorities tried to downplay the severity of the situation in Armagh. British Secretary of State Humphrey Atkins declared on 12 December that the women’s condition was “not yet giving any cause for concern”. In fact, the rapidity with which the three women were losing weight was indeed concerning. By the day of Atkins’s statement, each of the women had lost approximately 15lbs, meaning that they had lost more weight in their first 11 days than the men had lost in their first 26 days (the men’s average weight loss being approximately 11½lbs on 21 November.)

The strikers’ comrades recall noticing a rapid deterioration in their friends’ condition.

Síle Darragh described them as “emaciated” and “little more than bags of bones”. She recalls that the three grew incredibly pale and that “even their shoes seemed too big for their feet”.

Mairéad Farrell’s mother recalled seeing “a terrible change” in her daughter, whose face became so thin that she began to have difficulty speaking.

Although the women retained their strength and spirit, it was clear that the fast was taking its toll. Less than two weeks into the Armagh hunger strike, Síle was already preparing the women who were in line to replace the strikers in the event of their deaths.

The 1980 Hunger Strike ended in the H-Blocks on 18 December amid confused and chaotic circumstances as Seán McKenna’s fast reached a critical stage.

In Armagh Gaol, the three women were listening to the nine o’clock news on their smuggled radio and heard that the hunger strike was over. Their initial reaction was one of elation but caution soon took over. The women decided to continue their own fast until the news was confirmed by a republican source. A representative confirmed the news the following day and “The Armagh Three” declared an end to their hunger strike. It had lasted 19 days.

Like many of the republican women who fought in the Easter Rising one hundred years ago, the Armagh women were initially told by well-meaning leaders, ‘No, we don’t think it’s a good idea for you ladies to participate’. Like the women of the Rising, the Armagh prisoners refused to accept that response. They insisted upon their inclusion, upon being allowed an equal share in every aspect of the republican struggle.

The immense gains that women have made within the Republican Movement are largely thanks to women such as the Armagh POWs – women who would accept no less than equal opportunity and an equal voice: ‘We own this struggle. It is ours.’

To describe the Armagh women, I can think of no better words than those chosen for them by Bobby Sands: “A flaming inspiration.”

For anyone wishing to learn more about the Armagh women, I strongly recommend Síle Darragh’s book John Lennon’s Dead, available from the Sinn Féin Bookshop.

• Brodie Alyce Nugent is a PhD candidate at Flinders University in Australia currently in Belfast writing a doctoral thesis on the life and legacy of Volunteer Mairéad Farrell.