5 September 2016 Edition

Spike Island – a microcosm of modern Irish history

• Prison blocks sit empty on Spike Island

Beneath the soil are the graves of more than 250 mostly unknown prisoners

FOR tens of thousands of Irish people, a small rocky island in Cork Harbour was the last piece of Irish soil on which they set foot before being herded like cattle onto ships bound for far-flung British penal colonies.

One of those held on Spike briefly before his deportation was Young Irelander John Mitchel – after whom the fortress there is now named. Writing in his Jail Journal in 1848 after being convicted of sedition and treason felony for articles he wrote in The United Irishman newspaper, he described Spike Island as a “rueful-looking place”:

“In this court[yard] nothing is to be seen but the high walls and the blue sky. And beyond these walls I know is the beautiful bay lying in the bosom of its soft green hills. If they keep me here for many years I will forget what the fair outer world is like. Gazing on grey stones, my eyes will grow stony.”

Stepping off the small ferry that today services Spike Island, the first thing a visitor is struck by is just how physically close it is to the nearby bustling town of Cobh – the narrow streets, cars and people are easily discernible yet completely uncontactable.

• The nearby town of Cobh as viewed from the shore of Spike Island

People have called Spike Island, or Inis Píc, ‘home’ for well over a thousand years. It was originally the site of an ancient monastic settlement founded in 635AD by Saint Mochuda. Skip forward 1,000 years and the monastic site is just ruins, yet from the 1600s to 1938 Spike was one of the most important British military bases in Ireland. Even after the Anglo-Irish Treaty the British insisted on maintaining their presence on this small but strategically important little island – it was the keystone of one of the three “Treaty Ports”.

Spike’s life as a military base owes its beginnings to the American and French revolutions.

Jittery at the prospect of Ireland being used as a soft underbelly to attack England, the British began to fortify the island with artillery and guns to command the entrance to Cork Harbour. An attempted landing of French soldiers at Bantry Bay to help the United Irishmen in 1796 convinced the British of the need to garrison and defend one of the British Empire’s most important ports.

By 1804, work had begun on the formidable fortress dug into the island, consisting of six bastions surrounded by a dry moat and artificial slopes. It is almost invisible to approaching vessels.

• During Famine times over 2,3000 people were imprisoned on Spike Island

The Great Hunger of 1845 would dramatically change the history of this place.

On the most remote edge of the windswept south-west of the island, beyond a crumbling former ammunition storage building and across the old prison football field, is a small walled cemetery. The single Celtic cross and dozen smashed and badly-eroded headstones (their lettering illegible due to the elements) belie the reality that beneath the soil are the graves of more than 250 mostly unknown prisoners.

As a reaction to the Hunger, Britain began a policy of deportation of people they deemed to be criminals. Many of those thousands of Irish people herded onto boats from Spike had done nothing more than steal food or livestock in desperate bids to feed their starving families. The surviving records on display are filled with the words “burglary, theft, larceny and cattle rustling”. Others were ‘guilty’ of being homeless at a time when vagrancy was criminalised.

During An Gorta Mór, Britain had converted Spike into the largest prison in Britain or Ireland. With over 2,300 prisoners it was arguably the largest such facility in the world.

Between 1847 and 1883, more than 1,200 prisoners perished on the island. Overcrowding, poor sanitation and a shortage of medical care turned the prison into a death camp.

Newspaper reports from the time show inquests into deaths of prisoners due to allegations of “harsh treatment” generally absolved the prison authorities of any responsibility, instead attributing the deaths to the starving prisoners’ “delicate” health. Most of the dead were buried in another graveyard on the east of the island. This graveyard was later buried by the British military, officially during the upgrading of fortifications. Along with further protecting the island the upgrading also hid the horrific and brutal legacy for over a century.

Spike continued as a mainly military base for the next few decades. It was briefly used to hold the captured crew of The Aud, who scuttled their ship after being captured attempting to land guns for the Easter Rising in 1916.

During the Tan War, Britain was again in need of somewhere secure to hold hundreds of Irish people. Around 600 were on Spike at any time during the Tan War.

In April 1921 a dramatic rescue took place when three senior IRA prisoners, including Seán MacSwiney – brother of Sinn Féin Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney, who died on hunger strike – managed to break free from the fortress that was considered unescapable.

• The village square on Spike Island: The small community disappeared overnight in 1985 after it was evacuated due to rioting at the prison

Captain Michael J. Burke, who led the rescue effort, recalled how his IRA unit “commandeered” a motorboat in Cobh, raised the Union Jack to mislead British Royal Navy vessels and headed for the island. The three prisoners they wanted to rescue were being used to build a golf course for the British officers and they had managed to smuggle word in to them that they would be arriving near the shore at 10am. One of the prisoners, Thomas Malone, took a hammer he was using to mend a lawnmower and charged at a soldier who was armed with a rifle:

“I grabbed the rifle just above the muzzle and hit him in the temple with the hammer. He fell forward and I hit him a second time to make sure.”

Seeing this, two other guards quickly surrendered.

The attack unnerved the man piloting the boat. “He thought this was going a bit too far,” recalled Malone. “The boatman thought that killing a soldier with a hammer was involving him in something he was not prepared to get mixed up in.” It fell to ASU commander Seán Hyde to remind the boatman that he and his boat had technically been commandeered in the name of the Irish Republic and therefore, if arrested, he was to tell the British he was forced to take part in the events.

The Volunteers on the boat were just off the coast of Ringaskiddy when the engine gave out. Paddling towards the shore, they came under rifle fire from the top of Spike but managed to make it to shore with Thomas Malone occasionally returning fire using the rifle he had confiscated from the knocked-out soldier. Arriving on dry land, the Volunteers found that the getaway transport promised by the IRA was less than adequate:

“To my horror, I discovered that our transport consisted of a pony and trap!” said Burke. The three prisoners and Seán Hyde took off in the trap – making it to the mountains and managing to evade a military cordon. The four other Volunteers hitched a lift on a boat with a young boy to Monkstown. Miraculously, all managed to make it to safety.

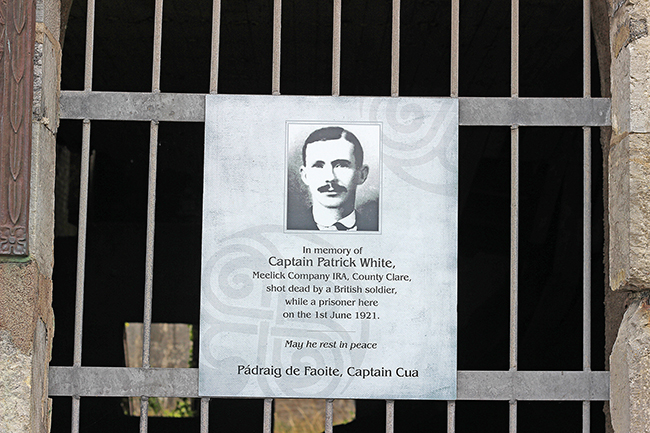

• A plaque marks the spot where IRA Volunteer Patrick White was murdered by a British sentry during a hurling match

At this time, prisoners were still dying on Spike. Shortly before the Truce in June 1921, prisoner Paddy White was murdered by a British sentry during a hurling match in the camp square. Two memorials to him (one unveiled in the 1950s and another more recently) mark the spot where he was killed.

Recounting the incident, Limerick IRA Volunteer Richard O’Connell said:

“We were out hurling and the ball went into the wire. Paddy White rushed over to pull the ball out with the hurley. If he got through that wire it would have been into his own hut, which had nothing to do with escaping from the place.”

The next thing was the soldier on sentry duty put up his rifle and shot White dead.

“We went over, knelt down and said a prayer for Paddy while he was dying. He died within a minute. We took him in then. The soldiers started mocking us while we were praying over White,” he said.

The prisoners maintained a guard of honour over their comrade before his body was transported to Cobh, and from there by train to his native Clare for burial.

Richard said he later learned how the soldiers on the island that day were from the Essex Regiment, which had recently suffered seven deaths in an IRA ambush at Crossbarry. The Volunteer says he believes the shooting of Paddy and subsequent taunting of the Volunteers was their way of exacting revenge.

The British finally handed back Spike Island to the Irish Government in July 1938.

A military outpost during “The Emergency” (the state of emergency during the Second World War), the island later reverted back to prison usage and remained in operation until 2004. In popular memory it is associated with joyriders, pickpockets and young offenders.

The prison and military garrison ensured the survival of a small village on the north of the island – mainly consisting of families of those employed there – until 1985, when prisoners took control of the fort. The Defence Forces were even deployed to quell the chaos. The small community disappeared overnight as the state informed them that they could no longer guarantee their safety. Today their homes along with their church, school and community buildings are slowly being reclaimed by nature.

With its last civilian residents departing in 1985, and its convict residents gone by 2004, Spike is today a national monument. Throughout its 1,400-year history, Spike Island has been a religious sanctuary, a place of learning, a place of immense suffering, an impenetrable fortress, an internment camp, a prison, and throughout it all inextricably intertwined with the history of modern Ireland.

• The small cemetery on Spike Island where over 250 prisoners are buried