6 June 2016 Edition

The living flame

Aftermath of the Easter Rising

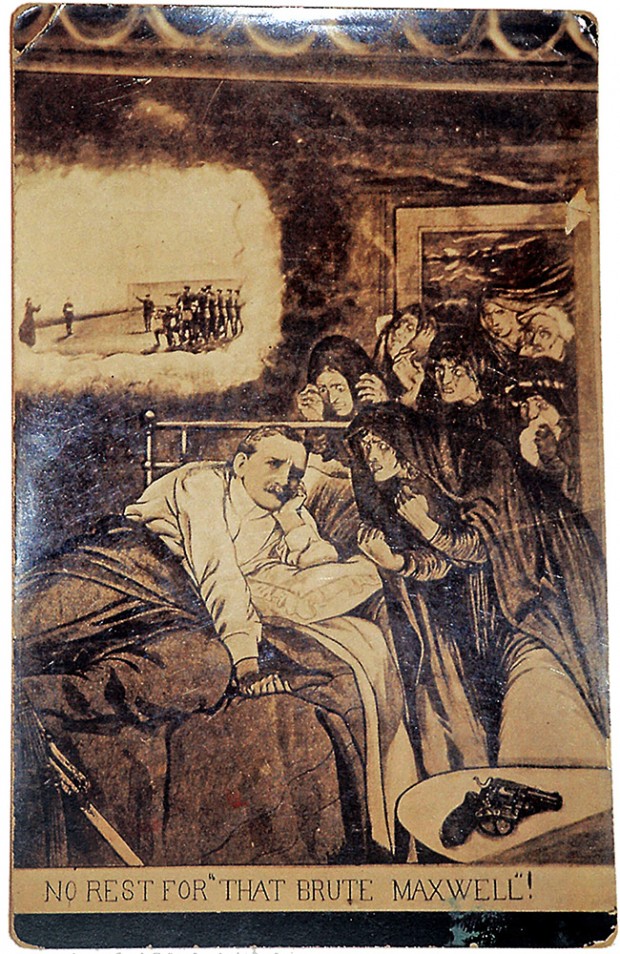

• General Maxwell was responsible for the executions

We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period, Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland – Lloyd George in a private letter to Edward Carson

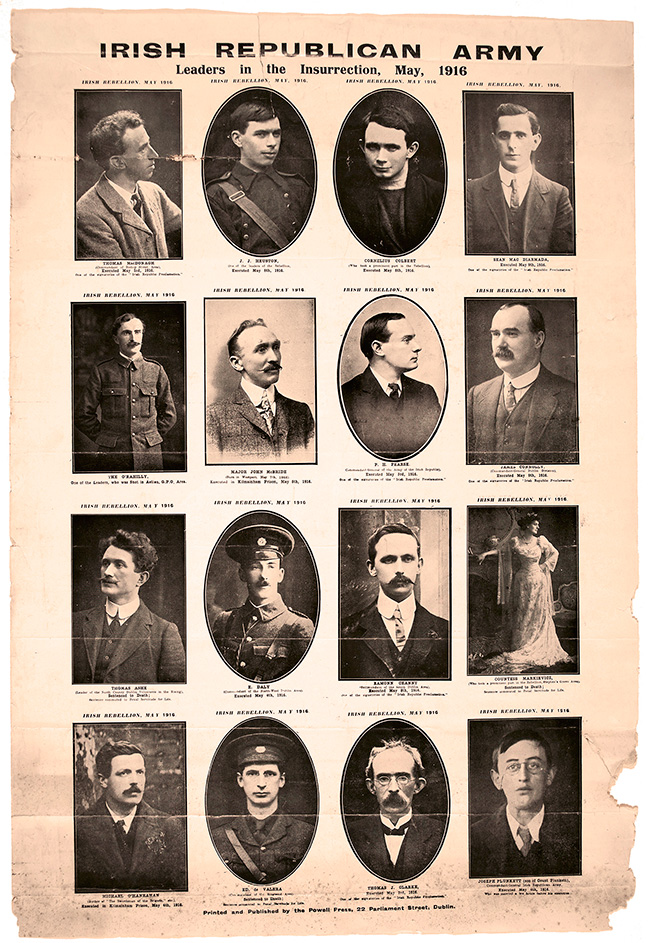

THE latter half of May and the beginning of June 1916 saw the slow turning of the tide towards Irish republicanism in the aftermath of the Easter Rising. What a poet called the “living flame” had not only been rekindled by the Rising but was about to flare up into a national political resurgence.

Many accounts of the Rising include descriptions of the insurgents being verbally and even physically attacked after the surrender by some of the population of Dublin. Many of these were “separation women”: the wives of men serving in the British Army who received a Separation Allowance from the British Government. Others were clearly well-heeled loyalists in the political sense, such as the women on Grafton Street who reportedly spat at captured prisoners.

The City and County of Dublin were under martial law and prisoners were being rounded up so it was certainly neither prudent nor safe for those supportive of the Rising to express their feelings openly.

But there is evidence from the accounts of insurgents and from others that during and after the Rising there were many people offering support. It was on this basis that wider support was built as public feeling reacted strongly against the executions of the leaders and the imprisonment of hundreds of people. In ‘The Irish Rebellion’, published in London in 1916, Canadian journalist F. A. McKenzie, who was not sympathetic to the Rising, wrote:

“I have read many accounts of public feeling in Dublin in these days. They are all agreed that the open and strong sympathy of the mass of the population was with the British troops. That this was so in the better parts of the city I have no doubt, but certainly what I myself saw in the poorer districts did not confirm this.

“It rather indicated that there was a vast amount of sympathy after the rebels were defeated. The sentences of the courts martial deepened this sympathy.”

• There was widespread public revulsion at the execution of many of the leaders

British military commander General Sir John Maxwell established the courts martial and was responsible for the execution of the leaders, 14 in Dublin and one in Cork. He refused to release the bodies to the families and insisted that they be buried in prison grounds (Arbour Hill Military Prison and Cork Detention Barracks).

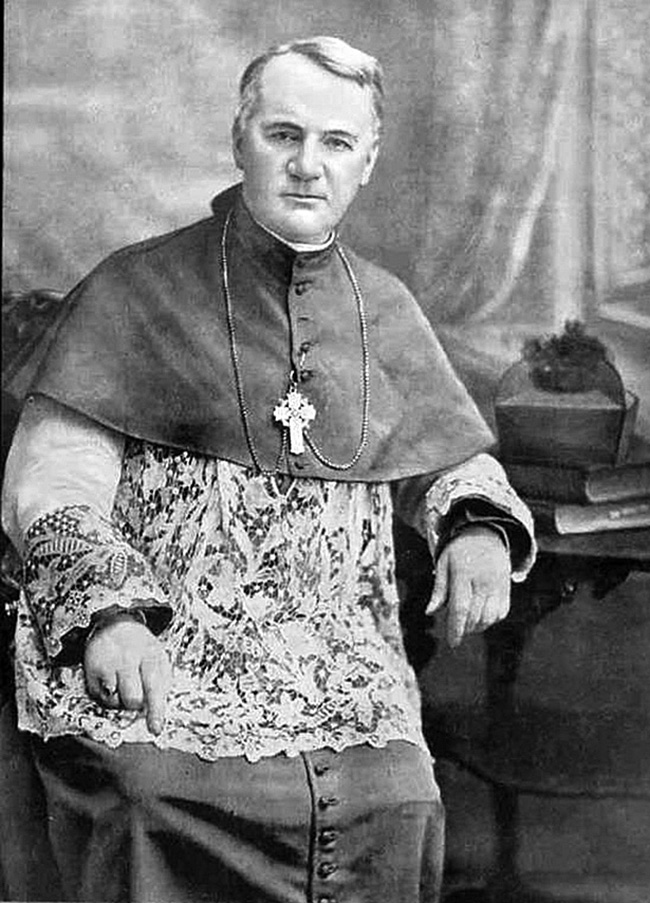

Public revulsion was expressed in dramatic public fashion by the Catholic Bishop of Limerick, Edward O’Dwyer. On 6 May, as the executions were proceeding, Maxwell wrote to O’Dwyer naming two priests in his diocese who were, said Maxwell, “a dangerous menace to the peace and safety of the realm” and requested that they be moved to some employment that would not involve contact with the public. Among the charges against the priests listed by Maxwell were speaking against conscription, attending a lecture by Pádraig Pearse, assisting the Irish Volunteers, and attending a meeting where Seán Mac Diarmada made “inflammatory and seditious speeches”.

In reply, on 17 May, Bishop O’Dwyer defended the two priests, described Maxwell as a “military dictator”, his actions as “wantonly cruel and oppressive”, and told him:

“You took care that no plea for mercy should interpose on behalf of the poor young fellows who surrendered to you in Dublin. The first information which we got of their fate was the announcement that they had been shot in cold blood. Personally, I regard your action with horror and I believe that it has outraged the conscience of the country. Your regime has been one of the worst and blackest chapters in the history of the misgovernment of this country.”

The letter was published and councils and other public bodies passed motions of congratulations to Bishop O’Dwyer for his stand.

• Bishop O’Dwyer to General Maxwell

Meanwhile, on 9 June, the British Government began transferring almost 2,000 Irish political prisoners to Frongoch internment camp in north Wales, which quickly became a “University of Revolution”. Seasoned Volunteers and members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood began to educate and train men from all over Ireland who had been interned without trial in the wake of the Rising. Other sentenced prisoners, including women, were dispersed in various English prisons.

On 10 June in Dublin and 23 June in Belfast, Irish Party leader John Redmond publicly defended the latest British Government proposals for partition and Home Rule. Lloyd George had them drawn up partly to relieve pressure from the United States over Irish self-determination after the executions and partly to advance the scheme to divide Ireland first hatched by the British Government in 1914.

Redmond threatened to resign his leadership if nationalists in Ulster did not accept the plan for “temporary” exclusion of Counties Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone from a future Home Rule parliament. Redmond’s position caused outrage and further undermined him and his party. The outrage would have been even greater had people at that time seen the private letter that Lloyd George sent to unionist leader Edward Carson:

“My dear Carson, I enclose Greer’s draft propositions. We must make it clear that, at the end of the provisional period, Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland.”