1 February 2016 Edition

Ghosts of patriots haunt Fine Gael and Labour

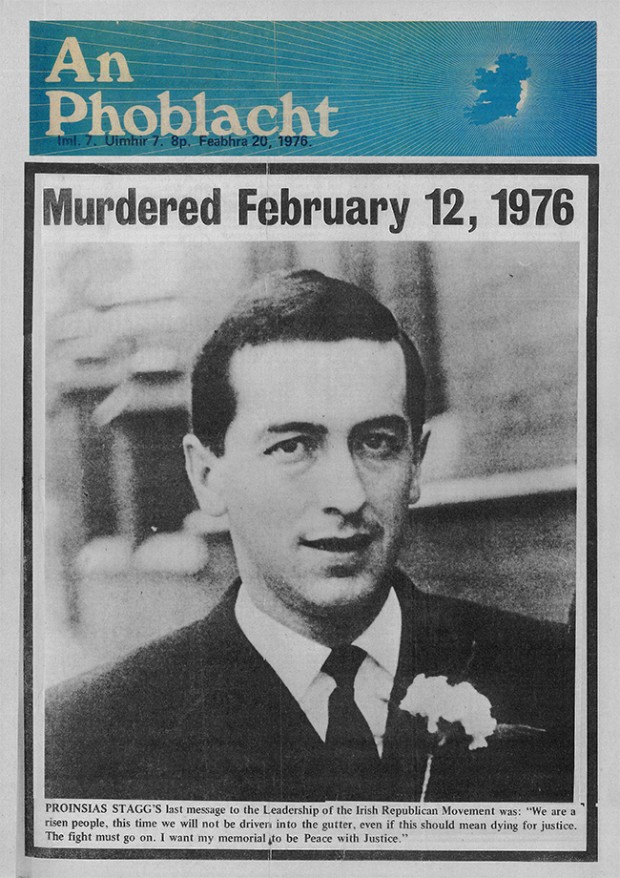

Frank Stagg – 40th anniversary

Remembering the Past

FRANK STAGG, from Hollymount, County Mayo, was an IRA prisoner in England. When he commenced his final hunger strike in Wakefield Prison, Yorkshire, on 13 December 1975 he had already endured several prison protest fasts. He had also been forcibly fed, a brutal practice that led directly to the death of his comrade and fellow Mayo man, Michael Gaughan, on 3 June 1974.

During his hunger strike, Stagg was denied religious services on the order of the Catholic Bishop of Leeds. Prison warders placed a coffin in a cell opposite Stagg’s so he could clearly see it. But this macabre act was as nothing compared to what awaited him after his death. He died on 12 February 1976 and in a last message to the leadership of the Republican Movement he said:

“We are a risen people. This time we will not be driven into the gutter, even if this should mean dying for justice. The fight must go on. I want my memorial to be Peace with Justice.”

In his will, Stagg had made clear that he wanted a republican funeral in Ireland and to be buried beside Michael Gaughan in the Republican Plot in Leigue Cemetery, Ballina. However, a Fine Gael/Labour Coalition Government was in power in Dublin. They were determined to prevent any public display of solidarity with a deceased IRA hunger striker as had happened when many thousands of people attended the republican funeral of Michael Gaughan through Dublin and across Ireland in June 1974.

Fine Gael Minister for Foreign Affairs Garret FitzGerald took the lead for the Coalition and contacted the British Home Secretary. FitzGerald vehemently opposed any contact between the British authorities and Sinn Féin to carry out Stagg’s final wishes for a republican funeral. Instead, gardaí were sent to London to accompany the body to Ireland. As family members and Sinn Féin leaders waited at Dublin Airport, the flight carrying Stagg’s coffin was diverted to Shannon Airport.

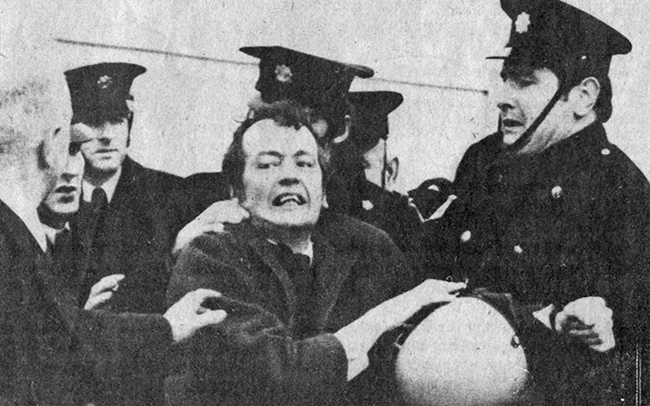

• Frank Stagg's brother Seán is manhandled by gardaí as they snatch the body at Shannon Airport

Family members were barred from the mortuary at Shannon and hundreds of gardaí and troops accompanied the body to County Mayo. Most of the Stagg family (including his mother, brothers and sisters) wanted to comply fully with his wishes. His widow Bridie and brother Emmet were persuaded by FitzGerald to co-operate with the Coalition, though his widow was not fully informed of what was to take place.

Emmet Stagg was a Labour Party member, later a TD and minister. In a letter to his father in 1975, Frank Stagg wrote:

“I suppose Emmet is still clinging to the coat-tails of Conor Cruise O’Brien and [Garret] FitzGerald. God help Ireland to be in the hands of such traitors.”

Frank included in his will a request that Emmet not attend the funeral.

In a final gruesome act, on 21 February 1976, gardaí buried Frank Stagg in a grave in Leigue Cemetery away from the Republican Plot. They poured concrete on the grave to prevent re-interment and placed a 24-hour guard on the cemetery. Speaking to thousands at a republican ceremony to honour Stagg in the cemetery the following day, Joe Cahill pledged that the hunger striker’s last wish would be fulfilled. This was done in November when the IRA reburied Stagg in the Republican Plot. Such was Garret FitzGerald’s fixation that when he was in Opposition in the Dáil in 1977 he asked if the Garda would move Stagg’s body back to the original ‘concrete’ grave!

• Emmet Stagg (back left) helps gardaí bury Frank Stagg away from the Republican Plot

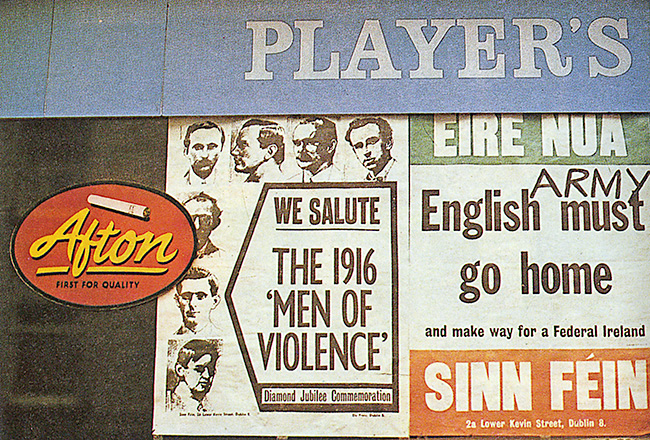

Within weeks of the hijacking of Stagg’s body was the 60th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. A decade previously, large-scale state commemorations marked the 50th anniversary. In 1976, there was no state event. Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave – son of 1916 veteran W. T. Cosgrave – led a Government for which 1916 was an embarrassment. Conflict was raging in the Six Counties as Irish republicans resisted repression by the British Army, the RUC and unionist paramilitaries. The jails, North and South and in England, were full of republicans. In 1974, Dublin and Monaghan had been bombed by loyalists acting in collusion with British crown forces, killing 33 civilians, but Cosgrave and his Cabinet blamed republicans for “provocation”. They tightened the broadcasting ban on Sinn Féin on TV and radio.

It was best not to commemorate 1916 as it threw up too many contradictions for the Coalition that was collaborating with British repression, locking up political prisoners and encouraging the anti-nationalist rewriting of Irish history. And they had just hijacked the body of a hunger-striker; the first republican to die on hunger strike was Easter Rising leader Thomas Ashe in 1917. So in 1976 the Fine Gael/Labour Coalition declared as unlawful Sinn Féin’s national 60th anniversary Easter commemoration in Dublin on Sunday 25 April. Thousands attended despite the ban. On the platform were James Connolly’s daughter, Nora Connolly O’Brien, and Fiona Plunkett, sister of Joseph Plunkett. Seventy people were later prosecuted for attending, including Fiona Plunkett and Labour TD David Thornley, who had participated in protest against the ban.

In 1976 it was not only the ghost of Frank Stagg that haunted Fine Gael and Labour but the men and women of 1916 as well.

• Poster supporting the 60th anniversary of 1916