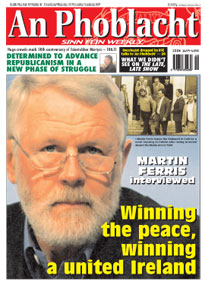

15 November 2007 Edition

INTERVIEW Martin Ferris - a life in struggle

Still fighting for a united Ireland

Sinn Féin North Kerry TD MARTIN FERRIS (55) is from Barrow, Ardfert, County Kerry.

Martin, in a manner of speaking, took the scenic route into the Dáil having travelled through various police stations, served a number of prison sentences, and made relentless escape attempts before eventually being elected a TD. He talks to ELLA O’DWYER about his life and being the newly-appointed Sinn Féin ‘United Ireland’ spokesperson.

What was it like growing up on a small farm in Kerry in the 1950s and 1960s?

There was myself and my brother, Brian, who is 17 months younger than me. We had a sister, Mary, who was born later, in 1955, but she only lived a few weeks. My mother, Agnes (Mullins), was a Limerick woman. Brian and myself had a very happy childhood – close to nature. Everything was produced at home: potatoes, cabbage – all the vegetables – and my father, Patie, kept a few pigs. He was apolitical. He’d vote for whoever needed it most. My mother was republican and when I stood for elections she’d vote for me. She was born in 1913 so she had the memory of the Civil War and her brother being dragged on the back of a lorry by the Free Staters through the streets of Tralee.

Did your mother’s republicanism impact on your own political awareness?

To a point, yes, but the mid-1960s was a very radical time. I was aware of the civil rights movement in America, particularly the racial tensions, and the student riots in Paris in the ‘60s, when young people took to the streets demanding their rights. Then on top of that you had the civil rights movement in the Six Counties where the nationalist people, who were denied their rights, became inspired by what they saw happening in the USA and in Europe.

So you joined the Republican Movement?

I joined the Movement in May 1970. I remember because it was actually the day my father was buried that I was approached by someone who asked me if I’d like to help out and I said, ‘No problem.’ About a week or ten days after that, I joined the IRA and it took off from there. I was going on for 18 years of age then.

Danny O’Sullivan, Bobby McNamara (who died recently) and myself were on the run from 1973 to 1975. I’d been away on active service and the police were looking to talk to me. From 1974 they were looking for me big time and I couldn’t go back to Kerry.

You had a couple of unfortunate Valentine’s Days, according to the record of your prison spells.

I didn’t think of that [laughs] but, yes, it was on 14 February 1975 when I was arrested first. [Martin was to be arrested again on 14 February the following year.]

The three of us were lifted together in Youghal, County Cork. The house we were in was surrounded. We got out of the house and into a graveyard but that too was surrounded and we were arrested there. The three of us were charged with the armed robbery of a co-op in Dungarvan, County Waterford, and with membership of the IRA. The other two men were convicted of the armed robbery and they got seven years each. I was acquitted of the robbery and done with membership. I got 12 months in Portlaoise.

You were involved in a number of escape attempts.

Yes. Like every IRA Volunteer I felt it was my duty to try to escape and to stay in prison voluntarily would have been a failure of your duty as a Volunteer. I was lucky enough to be afforded the opportunity when, on 17 March 1975, there was an attempted break-out and I was part of it. That was when Volunteer Tom Smith was killed and six POWs wounded. Brian Keenan was shot in the arm and leg.

Basically, the Free State soldiers panicked. Two men – Gerry Quinn and Eamon O’Sullivan – were coming in a lorry to break through the front gate when the engine died. We could hear the engine fading at the other side of the gate and we knew then that the game was up. None of us was aware at that stage that there was a man dead and we were rounded up in a corner of the yard.

I remember that JB O’Hagan was trying to get medical assistance for a man called Jack Murphy from South Armagh who had been badly wounded. Brian Keenan was wounded; he was still running around, trying to find a way out. In fact, himself and Kevin Mallon were trying to get behind the commanding officer of the Free State Army to try and jump him and take the gun off him. They hadn’t given up at that stage even though it was fairly obvious that we were going nowhere that time.

There were strip-searches and a bit of hiding for everyone that night.

You were released that November but not for long.

Yes, I got out in November ‘75 and I reported back as a Volunteer. Three months later, I was back in Portlaoise, charged with membership again. I got 18 months that time. That was 14 February again [laughs], in 1976.

Conditions deteriorated. In response, we decided to set fire to the prison in protest against the conditions in the hope that it would burn to the ground but unfortunately it didn’t – the walls stayed up.

We were put in solitary for a month and lost remission. There was an awful, aggressive physical response against the prisoners. William Reilly was the governor and he, along with what I would classify as the heavy gang amongst the prison service, did everything to try and break the Army structures and to criminalise us accordingly. I think it’s also significant that in March ‘76 the Brits tried to bring in their criminalisation policy at the same time. That was the beginning of almost nine months of gratuitous violence against the prisoners.

Solitary confinement was the norm for any resistance to their attempted criminalisation policy. Many of us spent most of that time up to March of 1977 in those conditions until we embarked on a hunger-strike in March 1977. It went on until May that year. Twelve of us finished it on the 47th day. I was released on 26 June, having served the full sentence as I’d lost remission during the hunger-strike.

That’s when you met your wife, Marie?

I met Marie for the first time at the prison gate on my way out. She had come to collect me along with a woman called Áine Lynch.

Marie is Australian and she was involved in Australia Aid for Ireland just before she arrived in Ireland the year before. Marie was from a strong republican family and was in Sinn Féin before I met her. We ended up getting married in 1978 and she was a rock, raising the children while I was in jail. She supported me all the way.

I went back to Kerry after my release in June ‘77 and at that stage there had been a lot of repression on the outside just as there had been in the jail: a lot of arrests and detention. A group of us got involved in rebuilding the Movement in Kerry. I was 25 years old at that stage.

At that time there was the painful situation in the H-Blocks with the blanket protest. It was tough trying to make people aware of what was going on because we were competing against Section 31 of the Broadcasting Act, which censored the voice of republicanism in Ireland on RTÉ TV and the radio stations.

Can you tell us a bit about the Marita Ann operation?

It was an IRA operation. I was involved in it along with four others. The plan was for the Marita Ann to rendezvous with the Valhalla in the Atlantic and transfer tons of arms and ammunition from the Valhalla onto the Marita Ann. Unfortunately, it didn’t succeed. We were apprehended off Skellig on 29 September 1984. We were about two miles inside the Irish waters limit. So obviously what happened was that the Irish Navy had two warships positioned in the area and apparently a third standing by in Valentia. The two vessels were hidden behind Skellig and our radar could only pick up the Skelligs Rock itself and not the ships and that’s how they came upon us. We tried to get the Marita Ann away but the navy vessels opened up with gunfire. Members of the navy, gardaí and detectives boarded us and we were arrested and towed to the naval base at Cobh. We were later driven to the Bridewell in Cork.

It was obviously a setback for the IRA – not that we were apprehended but because the arms and ammunition were badly needed to counteract the British occupation of our country. Three of us got ten years.

Pretty soon you were involved another escape attempt.

A year later, in November 1985, myself and 11 others tried to blow the main gate at Portlaoise Jail. Again we got to the gate but when the device went off it actually welded part of the arm that was holding the two gates together. It was bad luck. We got three months’ solitary after that in an isolation wing.

When Christmas Day came, the other men decided they’d refuse to eat their Christmas dinner in solidarity with us who were in solitary. I remember John Crawley, who was on the Marita Ann and also on the escape attempt with me, absolutely loved his food. Coming up to Christmas, he’d been canvassing for parts of the Christmas dinner that some of us mightn’t like so we’d all promised him bits of turkey and ham or whatever. We hadn’t told him that we were refusing the dinner. When the dinners came up, John was there with his knife and fork waiting to devour this huge dinner he was going to have and then we told him! [Laughs] I think John was more devastated about us refusing the Christmas dinner than he was about us getting an extra three years for trying to escape.

You got released in 1994. What then?

I came out in 1994 and we had an unstaffed, run-down office in Tralee. We used to just hold meetings there. Then a few of us came together to try to build politically on the ground. There was a whole new dispensation because I came out in October and the IRA had called a cessation the month before. It was a time of huge possibilities to build a political organisation. By the end of ‘97 we had started to build in the constituency significantly compared to what it had been in 1994. We stood for the general election in 1997 and took 5,600 votes, which was a huge surprise as we were ahead of Fianna Fáil until they got the transfers. Then we stood for Kerry County Council and Tralee Town Council in 1990 and got elected to both.

How did you feel when you were elected TD in 2002?

In the 1992 election we got 702 votes and in 2002 we got 9,600 votes. That says it all in terms of the progress made but I think what summed it all up for me was at the count in the Brandon Hotel, Tralee. I was hoisted on people’s shoulders and I remember looking at them and there were tears running down their faces. I was looking at people who’d given all their lives to the republican struggle, people who’d known nothing but hardship and had selflessly given everything they had to Ireland. They could see how everything had changed. It had been a collective effort on the part of committed republicans and it had paid off.

You’ve just been appointed as Sinn Féin’s ‘United Ireland’ spokesperson.

A united Ireland is what we’ve been about all our lives. Our existence is to bring about a united Ireland. I passionately believe that it will be a reality in my lifetime. I think there’s a huge job of work to be done in the meantime. We have to popularise the concept of a united Ireland and the benefits of that to the Irish people as a whole.

What I’m doing today I don’t see as any different to what I was doing from 1970. The British presence has been a negative and often brutal fact of life in Ireland. I’m very, very proud of having been involved in the IRA struggle because for most of my life there was no other way. Thankfully, I think we’re at a stage now when we can move forward and achieve our aims and objectives of Irish unification.

We have to ask ourselves if we have been adequately engaging with those who share our objective of achieving Irish unity.

I believe that most people on the island of Ireland want Ireland reunited. That’s the starting point and it’s how you structure that belief into becoming a reality. We need to popularise Wolf Tone’s vision of the unification of Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter – bringing people together and showing the benefits of that from economic and cultural points of view and in terms of healing differences and making a reality out of the aspirations of great people in Irish history.

What will this new role entail?

We have a number of events and initiatives planned to advance the united Ireland issue. It’s about creating awareness and mobilising public support for the cause of Irish Unity. We want to involve more people with us in working for this objective — it is time to put a new focus on building broad based alliances for unity including involving people from all sectors of society, for example artists, writers, film makers, academics, sports people, trade unionists and others. We’re appealing to everybody because reunification will be for the benefit of all. There’s also a huge role for the Irish in Britain and the USA. We want to galvanise the support out there for the Peace Process.

What about Sinn Féin now, in the aftermath of what was a disappointing election?

I think that, in the long-term, the outcome of the election will be beneficial to the party in terms of development. I think the momentum within the party over recent years hid some deficiencies that we can now identify. In a lot of areas the structures weren’t very developed and we need to get structures in place and more people in the party to complement the clear potential that’s there for Sinn Féin.

We also need to develop a Southern leadership, especially given that the biggest potential for Sinn Féin is in the 26 Counties.

All the turmoil, all the time on the run, all the time in jail – would you do it all again?

Yes, if I had to and with my family behind me as they have been, but times have changed and Irish republicans have a new job of work to do – winning the peace, winning a united Ireland.