28 October 2010

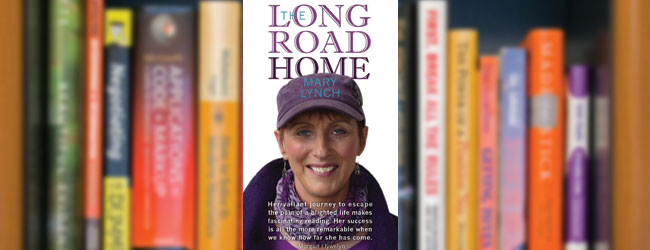

BOOK REVIEW | ‘THE LONG ROAD HOME’ – MARY LYNCH

Damaged goods: dealing with the legacy of childhood trauma

WHEN we think of children and trauma, we comfort ourselves with a few universal ‘truths’: children are resilient, they develop coping mechanisms, they will ‘get over it’.

Armed with these ‘truths’, adult protagonists, whether to a domestic row or armed warfare, carry on regardless of the impact on children.

In our own long war, republicans were not blameless in this regard. The reality was that children were caught up in IRA actions. Some died, others were physically injured and many more child witnesses to republican armed actions were left to ‘get over it’.

There is, however, a marked difference between the damage caused unintentionally to children as a result of revolutionary warfare and the deliberate abuse of children by state forces as a means of applying indirect pressure on the revolutionary.

The Lynch family of Baltreagh, near Lisnaskea in County Fermanagh, were one of thousands of families across the Six Counties to be at the receiving end of such abuse from crown forces over many years.

‘The Pitchfork Murders’

After painting an idyllic picture of children’s lives in rural Fermanagh prior to the conflict, Mary’s account identifies an incident in 1972 as the beginning of the end of childhood innocence.

While working at a farm near Newtownbutler, two young Catholic men, Michael Naan and Andrew Murray, were hacked to death. Their wounds were so gruesome that the incident was referred to as ‘The Pitchfork Murders’.

It was nearly 24 hours before news of the incident filtered out and several more years before the truth of what happened that night finally began to emerge, when a former member of the British Army’s Argyle & Sutherland Highlanders related how fellow soldiers had done the awful deed.

The message was that no Catholic was safe and that there would be awful consequences if the community allowed the IRA to operate in the area, a point driven home a few months later when another local man, Volunteer Louis Leonard, was killed in his butcher’s shop in Derrylin.

If such incidents were intended to strike fear into the heart of a community, they succeeded. But they did not prevent courageous young men and women stepping forward to fight back. Amongst those who volunteered were several of the Lynch brothers.

Raids

Their activism resulted in years of raids on the family home. The first of these traumatised Mary, as she woke to find a British soldier pointing a gun at her head, ordering her and her sisters downstairs.

The image of the family standing helpless and shivering on their kitchen floor while strangers ransacked their home stayed in Mary’s head but she ‘coped’ by internalising her fear and making sure that the strangers would not see her cry.

Such raids became part of life, as did long delays and threats at military and RUC checkpoints. Mary continued to suppress the trauma of such incidents, as did thousands of other teenagers of her generation who were not actively involved but were deemed guilty by association with a sibling or even a community that was regarded as republican.

Following a bomb attack on a hotel in which she worked in 1979, Mary was taken into custody, although never formally arrested. This ordeal was so horrendous that she didn’t tell anyone about it, instead blocking what had happened out of her own mind.

Getting away

It was at this stage that she began to ‘get away’ from it all, travelling to work in Germany and later to the United States. We find her on ‘The Long Green Line’ in New York during the Hunger Strikes and later shuttling back and forward to Florida or to other parts of the States.

Later back in Ireland and living with her husband in Roscommon, she learnt to say nothing, because there was no understanding (nor sympathy) towards the plight of the nationalist community in the North.

For this she blames years of media censorship and bias, recalling the contrasting responses to violence inflicted on the nationalist community as opposed to violence inflicted by republicans.

Her neighbours did not know that she had two brothers in the H-Blocks, one of whom became O/C of the prisoners. Even her own children were protected from this other life that she shared only with her parents and siblings.

To survive these years, Mary became a workaholic, but this ‘therapy’ could only take her so far and by the 1990s, the façade she had so carefully constructed to protect the wounded child, shivering on the kitchen floor, began to crumble.

The dark place

The secrecy and internalising of pain becomes too much in the end. For anyone who has suffered from clinical depression, Mary’s descent into the dark place is brilliantly and honestly related, as is her remarkable journey out of that place.

This is no quick-fix. Mary tried everything, from medication to meditation, from talking to others to talking to herself, from trying to forget to consciously trying to remember.

Even as we witness her finally ‘getting over’ her trauma, there are the occasional relapses, as the recurring image of the tortured child gives way to the young 18-year old, a bag over her head, a rope around her neck, being told by her RUC interrogators that her family will be shot and then being dumped out of a jeep in a lonely country road.

Time and again, we find her in a foetal position, crying her heart out.

But for all the pain within its covers, this is primarily a book about hope and Mary’s firm belief that in order to heal the wound, the victim has to deal with the burning hatred they hold for those who inflicted it.

For all the justifiable bitterness that she has felt over the years, Mary recognises that sustained bitterness really only damages ourselves. She learns to forgive, even if she can never forget.

Through her book, Mary Lynch has done a great service in highlighting a legacy of conflict that might otherwise be completely ignored. There are thousands of Marys out there; they carry no physical injuries but the emotional scars are deep.

Mary’s story can’t possibly describe the experiences of all these people, but it may prompt them to re-evaluate the impact of childhood trauma on their lives and to begin their own road to recovery.

• The Long Road Home, by Mary Lynch, is published by Londubh Books, Price €14.99/£12.99. Available from the Sinn Féin Bookshop, 58 Parnell Square, Dublin 1.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures