9 April 2024

Remembering 1981: Bobby Sands election

“Sands, Bobby. Anti H-Block/Armagh Political Prisoner, 30,492”. These words of election returning officer Alastair Patterson, became in 1981 the live televised public proof of the power of republican voters. Bobby Sands was elected MP for Fermanagh-South Tyrone 43 years ago on 9 April 1981. We republish two unique first-hand accounts of the events that led to Sands victory from Jim Gibney and Danny Morrison.

• — • — • — • — • — •

Key turning point in the struggle

BY JIM GIBNEY

First published, 6 April 2006

I hid behind the wall of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, less than 200 yards from the front door of Dungannon’s Electoral Office in Northland Row. From this safe distance I could watch, unobserved, the comings and goings at the Electoral Office. It was short of 2.30 in the afternoon, a warm day as I recall now, some 25 years later.

My inside jacket pocket held a little piece of paper, pregnant with historical change, of far reaching proportions for republicans. Of course at the time I was completely unaware of this. As I paced up and down the car park behind the Church I was more concerned not to be seen by anyone who would recognise me and be alerted to my intentions. The little piece of paper in my pocket was Bobby Sands’ nomination papers to contest the by-election for Fermanagh/South Tyrone.

In Ballygawley Road housing estate, a few miles away, Gerry Adams was sitting by a phone. He was in communication with republicans in Lisnaskea, the home town of the recently deceased MP for the constituency, Frank Maguire. Gerry was also in communication with me, not I hasten to add by mobile phone, they were yet to be invented, but through Jimmy McGivern a local republican in his car.

• Gerry Adams at a H-Block meeting, January 1981

Earlier Gerry had given me my instructions. They were simple enough. If by 3.50pm Noel Maguire, Frank’s brother, had not withdrawn his nomination papers from the by-election then I was to withdraw Bobby’s name from the contest. Four o’clock was the final deadline to withdraw papers. Three o’clock was the deadline for submitting a nomination. The leadership of Sinn Féin had decided Bobby Sands would not contest the election if there was another nationalist in the field.

At approximately 2.45pm the word from Gerry through Jimmy was that Noel Maguire was sighted in the company of a local republican in Lisnaskea shortly after 2pm. He had not been seen since then. The grapevine had it he had gone to ground. My heart sank with the news as I prepared myself to withdraw Bobby’s papers.

Then another courier arrived at the car park with a more positive rumour. Noel Maguire was on his way to the Electoral Office with the local republican but no one knew for certain why.

Lisnaskea was a difficult hour’s drive from Dungannon. We were all on edge. Would Noel make it to the Electoral Office before the deadline? Would he be stopped by the British Army at a checkpoint and delayed deliberately until after the deadline? Why was he coming at all if not to withdraw his name? Maybe he was just coming to tell the growing number of journalists outside the Electoral Office that he intended to stand?

I was not prepared to believe anything unless I saw it with my own eyes. Experience of the previous few weeks taught me that. It was packed with highs and lows as republicans grappled with what to do over the nomination of Bobby.

My anxious wait ended well within the time set for withdrawing a nomination. The solitary figure of the white haired Noel Maguire ascended the steps outside the Electoral Office. It was obvious he had decided to pull out of the contest. In keeping with his gentle demeanour he announced in a soft voice to the waiting journalists that he was withdrawing from the by-election because he had been told it would help save Bobby’s life. He could not have it on his conscience that any action of his would endanger another person’s life.

Noel Maguire’s gesture was not only magnanimous. It was a pivotal moment which shaped the future conduct of the republican struggle in a dramatic and unexpected way at the time. Had Noel stayed in the contest then Bobby Sands would not have been elected MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone because I would have withdrawn his name from the election. And the year 1981 might not have been the year the struggle changed so dramatically.

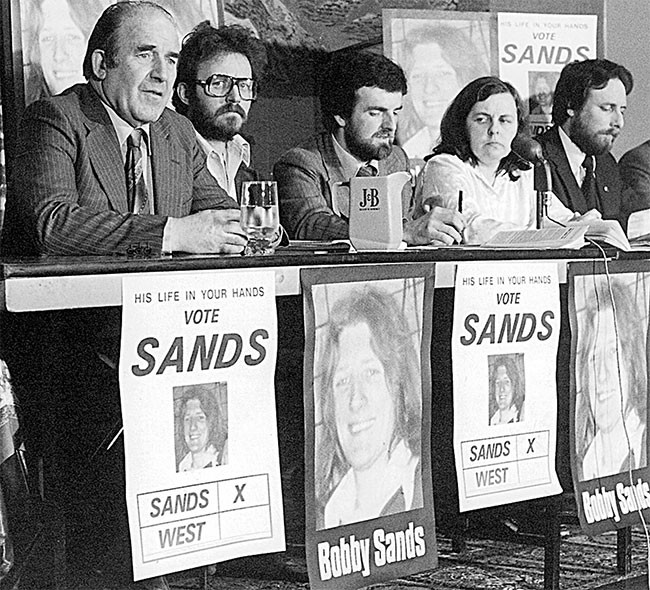

• Press conference to promote Bobby Sands’ election campaign, Enniskillen, Euro-MP Neil Blaney, Jim Gibney, Owen Carron (Sands’ election agent), Bernadette McAliskey and IIP councillor Pat McCaffrey

Bobby’s election rocked the Thatcher government and the Irish establishment. It also came as a huge surprise to many republicans with one very senior IRA man saying to me, as we watched the news of Bobby’s win on television, that it was worth 20 bombs. It was a spectacular victory against all the odds. It gave the prison struggle, and the struggle generally, a much needed boost.

Following Bobby’s election, Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew were elected TDs and other prisoner candidates did well across the 26 counties in that year’s general election. The election of two prisoner candidates as TDs was also significant for another reason. It ended Fianna Fáil’s reign as the dominant party in the south. They never again formed a government as a single party. That year also saw Owen Carron hold Bobby’s seat with an increased majority in the by-election caused by Bobby’s death.

In the middle of all that was happening and with Bobby’s win in the bag, I argued internally for Sinn Féin to contest the May local government elections held less than a month after Bobby’s success. Not surprisingly I lost the argument. Other organisations like People’s Democracy (PD), the IRSP, the IIP and pro-prisoner candidates did stand. The SDLP lost many of their council seats to these candidates including that of their leader Gerry Fitt who was still a Westminster MP at the time. Thereafter the struggle opened up a new front: contesting elections.

The election successes of 1981 gave republicans the confidence they needed to take the leap into the unknown electoral arena. I was not there for the internal debate which followed 1981. I was off to jail for the next six years. I can imagine it would not have been an easy debate to win. Republicans were very suspicious of participating in any form of struggle which they suspected was out of step with pursuing the armed struggle. For many in the leadership and elsewhere participating in elections was controversial and to be done selectively.

I was at an Ard Fheis in 1980 and heard Sinn Féin President, Ruaraí Ó Brádaigh denounce those republicans from Tyrone who put a motion to the conference to contest local elections in the Six Counties. Republicans in the 26 Counties were already contesting local elections. He warned delegates that anyone advocating such a course of action would face expulsion.

Between that Ard Fheis and Bobby Sands’ election there was a low level debate among some of the leadership of Sinn Féin about how best to build Sinn Féin into a popular political party and the role, if any, of participating in elections. The opposition to fighting elections was very strong. Indeed this was reflected in the extreme opposition among Fermanagh republicans to the proposal to stand Bobby.

I proposed standing Bobby in the by-election. It came to me in a flash on hearing the news on the radio of Frank Maguire’s sudden death. I thought it was a not to be missed opportunity to highlight the Hunger Strike and the protest for political status. I was to learn very quickly that not all republicans were taken by the idea.

The opposition in Fermanagh centred on the traditional republican hostility to elections. They were seen as a dangerous distraction summed up in the view that even if Sinn Féin won every seat in the country the Brits still had to be forced out by arms. There was also a genuine concern for the fate of Bobby and his comrades. Failure to win the seat would strengthen Thatcher’s main argument that the prisoners did not have popular support.

The opposition held out over several meetings against the combined persuasive powers of Ruaraí O Brádaigh, Daithí O Conaill, Gerry Adams and Owen Carron - all arguing to stand Bobby.

For republicans 1981 is, understandably so, one of the bleakest years of the conflict because of the deaths on hunger strike of the ten lads. It is also a seminal year in terms of opening up a new and challenging front, participating in elections. This led to other, equally important changes- taking seats in Leinster House and forcing republicans to build a serious party with a radical message.

It all started in earnest on 9 April, 25 years ago this Sunday, in Enniskillen’s Technical College, when the Returning Officer, in a breaking voice announced to the world, ‘Sands, Bobby, Anti H-Block/Armagh Political Prisoner, 30,492, West, Harry, Unionist, 29,046’. Bobby Sands was declared MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone.

• — • — • — • — • — •

Thirty thousand, four hundred and ninety two...

BY DANNY MORRISON

DANNY MORRISON was editor of An Phoblacht/Republican News and Sinn Féin Director of Publicity in 1981 and was a key contact between the protesting prisoners in the H-Blocks and the Republican Movement outside the jail. A former republican POW himself, Morrison was elected as a Sinn Féin member of a Six County Assembly in 1982. He became a full time writer in the 1990s. He is secretary of the Bobby Sands Trust. This article first appeared in the Andersonstown News on the 20th anniversary of the election of Bobby Sands.

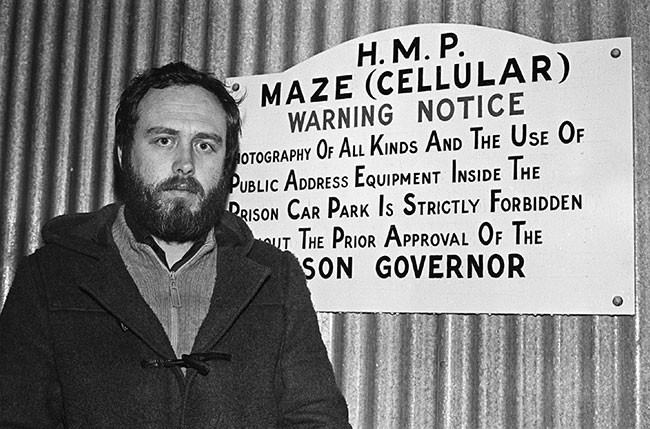

• Danny Morrison outside the gates of Long Kesh

9 April, 1981, the people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone went to the polls in a by-election to fill the seat held by the late Frank Maguire, an Independent MP, who died just five days after Bobby Sands began his hunger strike. Upon hearing of his death I doubt if any of us involved in the H-Block/Armagh campaign thought in terms of an election with a prisoner candidate. Firstly, the death of an MP does not automatically give rise to a by-election. A writ must be moved by an MP in the House of Commons to cause a by-election. Although republicans were friendly with some left-wing MPs, relations weren’t of the nature that they would do your bidding. Besides, such a call would have presupposed the existence of a concrete plan or strategy - when there was none.

Bobby Sands’ entry into Fermanagh and South Tyrone was an accident of history, and if there is one person who can be ‘credited’ with allowing that intervention then it is James Molyneaux, leader of the Ulster Unionist Party in 1981, and arguably one of that party’s most stupid.

Molyneaux thought that the nationalist vote would be split between the SDLP and an Independent candidate and that a single unionist candidate, in the form of former party leader, Harry West, would take the seat. It was only when the election was called that the idea was suggested that the Smash H-Block/Armagh campaign should make an intervention. Around about the same time that Bernadette McAliskey let it be known that she was prepared to stand but would stand aside for a prisoner candidate, others, most notably, Jim Gibney from Sinn Féin, were suggesting that Bobby Sands should be put forward.

A meeting was held in Monaghan and, incredibly, a small minority of Fermanagh republicans actually favoured the candidature of Noel Maguire, the former dead MP’s brother. However, at the end of the meeting it was decided to stand Bobby Sands, provided he got a clear run against West. Noel Maguire, under tremendous emotional pressure, eventually withdrew his name and the SDLP, fearing a backlash, decided not to put up a candidate, though Austin Currie threatened to stand and SDLP councillor Tommy Murray who signed Bobby Sands’ nomination papers was dismissed from the party.

I have never seen an election campaign like it. Thousands of activists were mobilised from across Ireland to go to Fermanagh and South Tyrone to help out in the postering and canvassing. In Dungannon and Enniskillen offices were opened round-the-clock. Some of us from Belfast went up, thinking we were going to teach the locals how to run an election. What we discovered was that working quietly away in the background for decades were people who had dedicated themselves to the electoral registers, ensuring that everyone of voting age was on the rolls, that the sick or those overseas were registered for postal votes, that people were trained in the science of organising an election and supervising the count. They were brilliant.

At after-Mass meetings people would emerge from chapel, stand and listen, applaud and then make generous contributions to the fighting fund. I remember a group of Belfast women return to the election office in Dungannon totally despondent about Bobby’s chances after they got an extremely cold reception outside a church on the Ballygawley Road. Francie Molloy asked them to describe exactly where they had made the speeches. It turned out they had been addressing and leafleting parishioners leaving a Church of Ireland service!

In Enniskillen on the day of the count we felt in our bones that Bobby was going to win. You just knew it from the atmosphere, the people flocking to the polling stations, queueing to vote. In the afternoon when the returning officer declared the vote I couldn’t contain myself and let out a huge yell.

For years the British government had been denigrating republicans, declaring they had no support, challenging them to go to the ballot box. Bobby Sands got 30,492, with a majority twice as large as Thatcher’s in her constituency of Finchley. Bobby’s election agent, Owen Carron, made Bobby’s acceptance speech and called for dialogue to resolve the hunger strike. Harry West got up and began to make his victory speech, then appeared confused, then realised that the unthinkable had happened - Bobby Sands had won!

That night I came back to Belfast with Mr and Mrs Sands and Bobby’s sister, Marcella, and went into town to do more interviews. In the car we discussed the impact of Bobby’s victory and the hope it gave that his life might be saved, that Thatcher would be compelled to recognise his mandate. But that was not to be. Her reaction was to amend the Representation of the People Act so that no Irish political prisoner in any jail in the world could contest a Westminster election. British governments were later to continually amend electoral rules - on identification, on deposits, on local government oaths - all with the objective of excluding republicans, and all of which failed because Sinn Féin circumvented all obstacles by simply adopting a pragmatic approach.

Republicans and electoralism could have ended there in 1981, had not James Molyneaux, again inexplicably, moved another writ for another by-election! Because of the exclusion of prisoner candidates, this time Owen Carron, a member of Sinn Féin, standing on an anti-H-Block/Armagh prison ticket, was nominated and was elected, increasing Bobby’s vote, in yet another dramatic election. Owen’s election took place on 20th August, the day on which Mickey Devine became the last hunger striker to die.

In voting for Bobby Sands and Owen Carron the people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone rejected British rule and asserted the integrity of the prisoners and the cause of Irish independence. They provided the springboard for the electoral rise of Sinn Féin and the empowerment of the general nationalist population in its unrelenting challenge to unionist and British misrule.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures