25 May 2023 Edition

Lions in slumber

The United Irishmen and revolution in England

On the 225th anniversary of the 1798 rebellion Joe Dwyer delves into an overlooked part of early Irish republican history – that of republicans in Britain and the allies they found there.

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

In Madden’s ‘The United Irishmen: Their Lives and Times’, it is said that the Belfast-born United Irishman, William Putnam McCabe recruited many ‘disciples’ in England, and that “he was not wholly unconnected with the disturbances that prevailed in London in 1800; the desperate project of Colonel Despard in 1802; and the attempt at rebellion by the Wastons and Thistlewood, long afterwards”.

Even without further detail, the allusion towards United Irish cooperation with English radicals is a tantalising prospect.

However, by tracing key personalities and events, it is possible to piece together an intricate tapestry of reformers, rebels, and republicans – Putnam McCabe among them – who conspired to foment revolution on both sides of the Irish Sea.

The London Corresponding Society

In the wake of the American and French revolutions, reform societies proliferated across Europe. Coffeehouses and taverns became bastions of radical fervour, and nowhere was this truer than in London, the very heart of the British Empire.

The London Corresponding Society (LCS), founded in 1792, was rapidly gaining support through its popular campaign for electoral and parliamentary reforms. But, as France had demonstrated, cries for reform can rapidly become cries for revolution. Accordingly, the British authorities moved against the budding LCS in May 1794.

Leading LCS members, John Thelwall and Thomas Hardy, were arrested for high treason, alongside the radical writer John Horne Tooke. The three trials, popularly known as the ‘Treason Trials’, would provide an early propaganda victory for the LCS.

The State’s case was ably dismantled by defence counsel. Indeed, Tooke even called upon the Prime Minister himself, Pitt the Younger, as a character witness. In an embarrassment for the government, Pitt conceded from the witness stand that he too had once advocated for parliamentary reform. The three were cleared of all charges and LCS membership ballooned.

The Brothers, the Colonel, and the Priest

This new momentum coincided with the emergence of a younger, increasingly more radical, LCS leadership. The Dublin-born brothers, Benjamin and John Binns, were among this new crop.

The Binns were both sworn United Irishmen and soon began steering the LCS beyond pleas for mere reform and towards outright calls for rebellion. As John Binns later reflected, “the wishes and hopes of many of its influential members carried them to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic”.

A fellow United Irishman rising in the LCS ranks was Colonel Edward Despard. A member of the landed-class, Despard had fought with distinction in the Britain Army and even served alongside a then little-known Horatio Nelson.

However, Despard’s refusal to recognise racial distinctions in law, while serving as superintendent of the Bay of Honduras, terminated his military career early. Returning to London, the young Colonel was invariably drawn into the orbit of the London-based United Irishmen and LCS.

In June 1797, Father James Coigly, a United Irish organiser from Armagh, arrived in the English capital. With preparations for an Irish uprising already underway back home, the potential for diversionary unrest in England was appealing.

The charismatic, 6ft tall priest cemented formal co-operation between the United Irishmen and LCS militants. Government spies were soon furnishing reports of LCS meetings in the cellar of Holborn’s Furnival’s Inn, addressed by Father Coigly, Colonel Despard, the Binns brothers, and Valentine Lawless, the official United Irish representative to London.

Over the summer, Father Coigly embarked on a tour of the north-west of England, enlisting textile workers in Yorkshire and Lancashire as sworn ‘United Englishmen’. Meanwhile, John Binns toured the south-east, addressing reform rallies on behalf of the LCS.

As later events shall demonstrate, it is notable that Binns stopped in places like Portsmouth, near Spithead, and Chatham, near the Nore.

• ‘Treason Trials’ - John Horne Tooke called upon the Prime Minister as a character witness, LCS members were cleared of all charges in an early propaganda victory

The Floating Republic

During this period, conditions within the Royal Navy were notoriously brutal. Pay was poor and rations were scarce. As recruitment dwindled, lawbreakers were increasingly sentenced to serve the Crown-at-sea, as an alternative to imprisonment. Indeed, government officials would later estimate that as many as fifteen thousand United Irishmen and Defenders might have been sentenced into the Royal Navy between 1793 and 1796.

In April 1797, the Navy was rocked by a series of mutinies. Beginning at Spithead before spreading to Plymouth. Red flags were flown from masts and mutineer councils were elected.

Before the Spithead situation could be resolved, the naval fleet at the Nore also mutinied. However, when the Nore’s so-called ‘Floating Republic’ sailed up the River Thames, the river’s marking buoys were deliberately removed by the authorities, and the mutinous fleet soon found itself stranded.

The United Irishmen leader, Theobald Wolfe Tone, moored at Texel, lamented the defeat of the mutineers, recording, “The English navy was paralysed by the mutinies at Portsmouth, Plymouth, and the Nore; the sea was open and nothing to prevent both the Dutch and French fleets to put to sea”.

In a subsequent government inquiry, it was suggested that United Irish networks had been operating on some of the mutinous vessels. Robert Lee, who was hanged for his part in the Plymouth mutiny, was found to be the brother of well-known United Irishman Edmund Lee.

The Margate Five

Despite the naval mutinies, most English radicals still eschewed outright revolution. William Putnam McCabe, now the United Irishmen’s emissary to Britain, undoubtedly spoke for many when he branded John Thelwall “a damned cautious fellow”.

Despite this, United Irish activity in London persisted. Under Colonel Despard’s supervision, the militants within the LCS now reconstituted themselves as ‘United Britons’.

As Marianne Elliott notes, between 1796 and 1798, the United Irishmen had successfully “annexed an existing democratic network and republicanized it to an extent which the militants in the London Corresponding Society could never have achieved alone”.

In January 1798, the LCS issued a statement denouncing British rule in Ireland. The following month, a United Irish delegation left London for Paris to appeal to the French Directory for military assistance. The leading United Irishman Arthur O’Connor was chosen to head this clandestine mission. Accompanied by John Binns, Father Coigly, and John Allen, a Dublin-based United Irishman.

However, O’Connor insisted on bringing a large quantity of luggage and his servant, Jeremiah O’Leary, on the escapade. The mountain of trunks, accompanying military accoutrements, and Irish accents soon caught the attention of the authorities.

In the early hours of 28 February 1798, the five men were arrested at the King’s Head, Margate and charged with high treason.

At trial, O’Connor, Binns, Allen, and O’Leary were found not guilty. But Father Coigly, who was apprehended with an appeal from the ‘Secret Committee of England to the French Directory’ in his coat pocket, was found guilty.

The rebel priest was hanged on 7 June 1798. On hearing the news, Wolfe Tone pledged, “If ever I reach Ireland and that we establish our liberty, I will be the first to propose a monument to his memory…”

The English Bastille

The Margate arrests rocked the nascent republican movement in England. Many fearful conspirators now turned informer.

On 12 March 1798, Colonel Despard was picked-up in his Soho lodgings. The Times later sensationally reported how the Colonel was arrested in bed with “a black woman”, failing to mention that the woman was Catherine Despard, his wife.

While their interracial marriage was unique for the time, the Colonel’s high social-status and past military prestige had arguably, up until this point, shielded the pair from spiteful public commentary and scandal. Now a confirmed rebel however, there was no such consideration afforded.

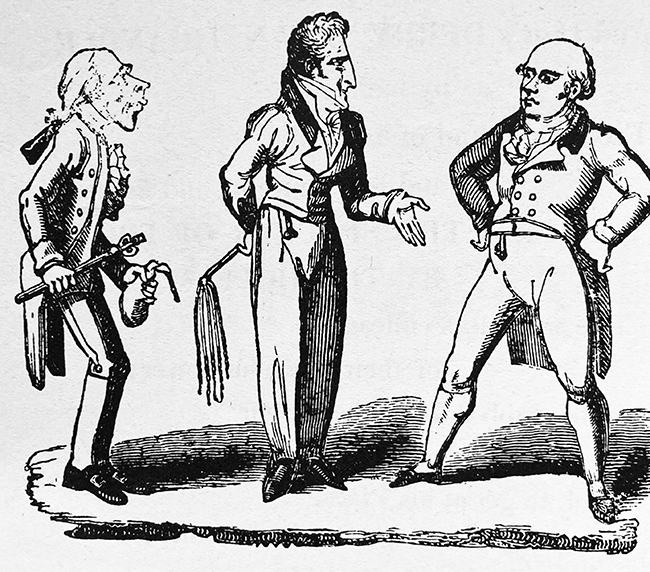

• Colonel Edward Despard

With habeas corpus suspended, the Colonel was dispatched to Coldbath Fields Prison, widely known as ‘the English Bastille’. He was put in a cold cell, without light, and placed on a bread and water diet.

Fearing for his health, Catherine launched a public campaign to have him relocated. She enlisted the support of Sir Francis Burdett, a radical Member of Parliament, in this endeavour. Burdett’s advocacy generated an international cause célèbre and Colonel Despard’s incarceration became the focus of a three-week debate in the House of Commons. As a consequence of Catherine’s efforts, the Colonel was eventually moved to better conditions.

The Despard Plot

In March 1801, Despard and his fellow political prisoners were released. In no time, the government was again began receiving reports of United Irish activity in the English capital.

According to informants, Despard now headed a secret committee overseeing cooperation between United Irishmen and what remained of the United Britons/United Englishmen. In the summer of 1802, William Putnam McCabe was spotted in London, in the company of a resurfaced Colonel Despard.

The Colonel enlisted William Dowdall, a veteran United Irishman, to travel to Dublin to ascertain what appetite there was for another Irish uprising, following the defeat of 1798. His investigation neatly aligned with Robert Emmet’s own designs for rebellion.

Despard proposed a wave of attacks against high-profile targets in London, to coincide with any Irish uprising. The Tower of London, the Bank of England, and London’s armouries would all be seized. If successful, the King would be killed, and mail-coaches would be prevented from leaving the capital.

Unbeknownst to the Colonel however, his inner circle was already infiltrated by government spies. On 16 November, Bow Street Runners burst into a secret meeting in Lambeth’s Oakley Arms and forty conspirators were rounded-up.

Despite a heartfelt character reference from the now widely celebrated Admiral Horatio Nelson, the Colonel was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death.

Alongside six co-defendants, Despard was hanged on 21 February 1803. In July, Emmet launched his abortive rising in Dublin. In his Proclamation, Emmet specifically noted that his plans had not been deterred by ‘the failure of a similar attempt in England’.

The Spenceans and Spa Fields

Towards the end of the decade, reform rallies had almost become a national pastime. Sir Francis Burdett, who had vociferously protested against Despard’s imprisonment, was a leading light of this renewed campaign for reform, alongside the celebrated public speaker, Henry Hunt.

A new radical society, the Spencean Philanthropist Society, had also entered the frame. The Spenceans followed the teachings of the English pamphleteer Thomas Spence. They were led by Doctor James Watson, his son Jem Watson, and Arthur Thistlewood.

A government spy would later caution that Thistlewood, like Despard before him, could pass for “quite the gentleman in manners and appearance”. In 1814, Arthur Thistlewood visited Paris and met with the now exiled William Putnam McCabe.

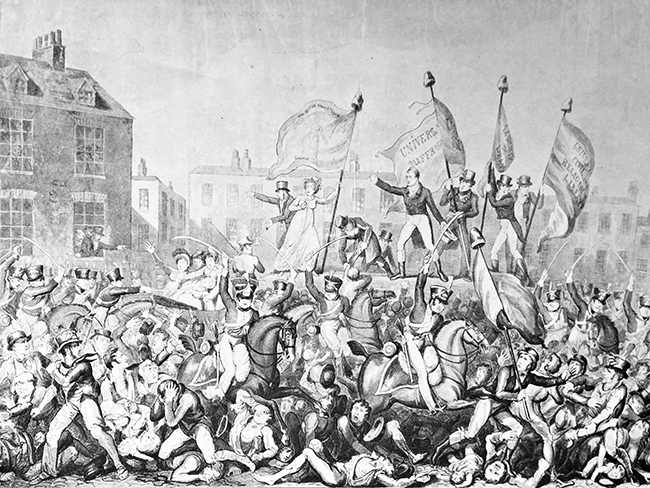

In 1816, the Spenceans persuaded Henry Hunt to address a mass meeting in Spa Fields, north London. On 15 November, thousands flocked to Spa Fields to hear ‘the Orator’ Hunt speak. A petition addressed to the Prince Regent calling for reform was passed by acclamation.

Another follow-up public meeting, ostensibly to hear the Regent’s reply, was agreed for 2 December. However, Thistlewood and the Watsons had different intentions for this next gathering. Over the following weeks, spymasters received whispers of a planned assault on the Tower of London.

On 2 December, just as Jem Watson concluded a rabble-rousing address, rallying those assembled to march en masse on the Tower, the celebrated, but notoriously vain, Henry Hunt arrived on the field, conspicuously late.

Out of the thousands present, only a few hundred broke away to follow the young Watson. With most remaining behind to hear to the delayed Hunt speak.

Watson’s rag-tag followers proceeded through the streets of London, raiding gunsmiths and brandishing weapons. But, when faced with armed cavalrymen waiting for them at the Tower, the mob dissipated.

Jem Watson fled the country but his father, Doctor Watson, was subsequently arrested and charged for the ‘Spa Fields Riots’.

Although the older Watson was eventually acquitted, the ‘Spencean plot’, as outlined at trial, echoed ‘Despard’s plot’ from fourteen years previously; including the seizure of the Tower of London, an attack on the Bank of England, and the raiding of local arms depots.

Curiously, William Putnam McCabe had travelled to London in secret during this period and was said to be present at Spa Fields that same day.

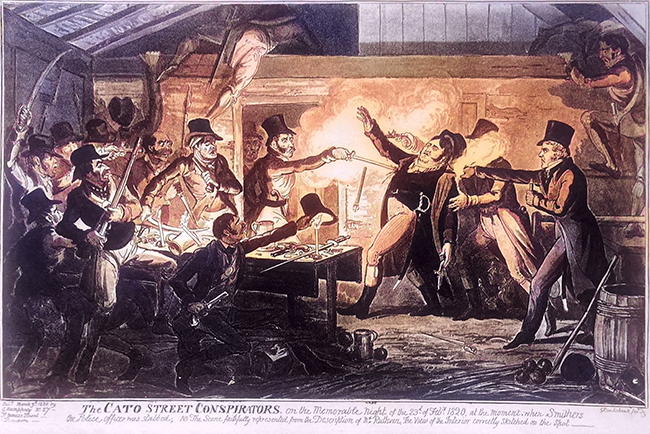

• Arrest of the 'Cato Street conspirators'

Conspiracy on Cato Street

Reeling from the failure of Spa Fields, Arthur Thistlewood began devising another trigger-point for rebellion in London. He increasingly became consumed with the idea of assassinating leading Tory Viscount Castlereagh.

Castlereagh was already widely detested in his native Ireland for his suppression of the 1798 rebellion. He was also despised among English radicals for his defence of the yeomanry following the ‘Peterloo Massacre’ of August 1819.

As a government informer later reported, Thistlewood became convinced that, “The death of Lord Castlereagh would rouse the Irish and the whole country would be in confusion...” Thistlewood hoped to enlist the Irish in London to his cause, particularly a conclave of tenement houses in Gee’s Court just off Oxford Street.

However, on 6 April 1820, Thistlewood’s hopes were dashed. A secret meeting of his conspirators above a stable on Cato Street was ransacked by Bow Street Runners.

• Caricature of Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, (centre) with a whip, a reminder of his regime in Ireland

The ‘Cato Street conspirators’ were tried and found guilty of high treason. Five men were sentenced to death; Arthur Thistlewood, Richard Tidd, James Ings, John Thomas Brunt, and William Davidson.

Tidd was a veteran of the ‘Despard plot’ and, just before the hayloft was raided, Thistlewood had warned those gathered, “If we drop the thing now, it will turn out another Despard’s Job”.

During their trial, successive prosecution witnesses testified that, alongside targeted assassination, the conspiracy also intended a co-ordinated attack on the Tower of London, Bank of England, and London’s arms depots.

This evidence caused unease for the authorities. Such testimony clearly mirrored the trials of both Doctor Watson and Colonel Despard from years before. A pattern of prosecution witnesses retelling the same tale, from one trial to the next, could be characterised as paid informers parroting a tried and tested formula.

However, it is equally true that sometimes informers do tell the truth. Arguably, this was the real cause for establishment discomfort.

It remains possible that Cato Street, like Spa Fields before it, and the Despard Plot before that, all flowed from the same United Irish initiative to rouse revolution in England. As R.R. Madden might term it, perhaps they were ‘not wholly unconnected’.

‘Rise like Lions after slumber,

In unvanquishable number

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many–they are few.’

Lines taken from The Masque of Anarchy, Percy Bysshe Shelley which was written in response to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre.

Timeline

November 1794 — The 'Treason Trials'

*********

April 1797 — The Spithead and Nore mutinies

*********

June 1798— Execution of Father James Coigly

*********

November 1802— 'The Despard Plot' is uncovered

*********

February 1803 — Execution of Colonel Despard

*********

December 1816 — 'The Spa Fields Riots'

*********

August 1819— 'The Peterloo Massacre'

*********

April 1820 — The Cato Street Conspiracy' is uncovered

*********

• Joe Dwyer is the Sinn Féin political organiser for Britain