9 April 2023

Centenary of the death of Liam Lynch

• Liam Lynch

By April 1923 the British and Free State counter-revolution had succeeded in suppressing the Irish Republic and the IRA faced military defeat.

The IRA Chief of Staff and his comrades were on the run with Free State forces closing in on them. The rapid rise of Liam Lynch to national leadership was to come to a tragic end, and with it the Civil War which he had tried hard to prevent but which, when peace efforts failed, he had fought determinedly for ten months.

Liam Lynch was born in Barnagurraha, County Limerick in 1893. He commanded the Cork No 2 Brigade of the IRA during the ferocious days of the Tan War. He would eventually rise to command the 1st Southern Division.

Lynch was a principled Republican as well as a military leader as became clear when on 20 August 1919, Dáil Éireann agreed an oath to the Irish Republic to be taken by all its members and by all IRA Volunteers. The first major action after this significant development and the first concerted attack on the British Army since 1916 was in the town of Fermoy, County Cork. It was led by Liam Lynch.

The aim of the ambush, as with most such operations in 1919, was to capture badly-needed weapons. The decision to mount the attack was a daring one given the overwhelming numbers of British forces in the garrison town of Fermoy and the fact that the Volunteers were armed only with revolvers.

An armed detachment of British soldiers marched each Sunday from their barracks to the Wesleyan church in Fermoy. On 7 September 1919, there were 15 soldiers in the detachment and waiting for them were some 25 members of the local IRA company. They had only six revolvers between them and were stationed in groups of two and three in the vicinity of the church. Two cars were ready to take the captured rifles away, the first near the church and the second following the military detachment.

When the British soldiers reached the church they were overtaken by the second car carrying Liam Lynch. He called on them to surrender. They refused and there was a confused struggle between the soldiers and the IRA Volunteers. One British soldier was killed and three were wounded. The captured 15 rifles were taken away in the cars and outside the town trees were felled in their wake to prevent pursuit by British vehicles.

Within hours of the ambush, the British Army began intensive raids and searches in the surrounding countryside.

The following night, soldiers from the barracks invaded the town and smashed up and looted shops in the main streets of Fermoy.

Two nights later, they appeared for a repeat performance but were forced back to barracks when they were attacked by townspeople armed with sticks and stones.

The Fermoy reprisals were the first such revenge raids by the British Army and many worse were to follow once the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries were introduced. Lynch’s Brigade was very much to the fore in the fight against the British forces.

One of the participants in the Fermoy ambush was a close friend and comrade of Lynch’s. He was Michael Fitzgerald, O/C of the First Battalion, Cork No 2 Brigade, and secretary of the Fermoy branch of the ITGWU.

Arrested after the Fermoy action, he was held in Cork Jail where he embarked on hunger strike. He died on the fast on 17 October 1920, followed within days by his fellow prisoner in Cork, Joseph Murphy, and by Cork Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney in London. The death of Fitzgerald had a lasting impact on Liam Lynch.

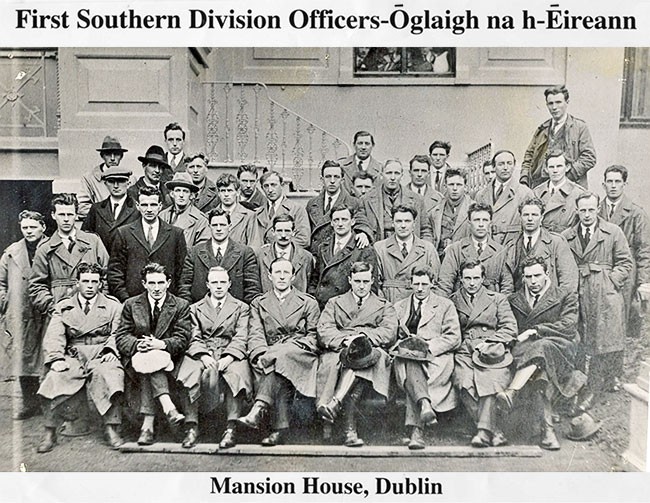

• Liam Lynch (front, fourth from the left), April 1922

By the time of the Treaty of December 1921 Liam Lynch was commanding the First Southern Division of the IRA. His opposition to the Treaty was hugely significant militarily and politically given the strength of the IRA in Munster. But Lynch was determined to maintain the IRA intact and avoid a civil war. He was deeply involved in peace efforts between January and June 1922.

These efforts faltered under British government pressure and the swift development of its own Army by the Provisional Government of the Free State. While Lynch had strategic differences with Rory O’Connor and the IRA Executive which occupied the Four Courts in April 1922, there was no essential difference in principle or policy.

When the Free State bombarded the Four Courts at the end of June 1922, they gambled that Lynch might stay out of the fight. They were gravely mistaken and Lynch returned south from Dublin to fortify what later writers dubbed the ‘Munster Republic’, though Lynch never used this term.

While Lynch’s forces were substantial and held many strategic positions at first, they could not hold out for long against the militarily stronger Free State forces, especially given the division of the civilian population over the Treaty. The Free State use of mass imprisonment, executions inside and outside the prisons, the bitter hostility of the Catholic hierarchy and the press, all conspired against dwindling Republican forces in the winter and spring of 1922/23.

It all came down to the early hours of the morning of 10 April 1923. Over 1,000 Free State soldiers, under the command of Major General John Prout of Waterford Command, began a search and sweep operation of the Knockmealdown Mountains on the border of Counties Tipperary and Waterford.

Liam Lynch, with fellow IRA officers including Frank Aiken, had arrived in the area to attend a reconvened conference on the continuation of the war and what options were open to the IRA leadership.

The conference had begun on 23 March in a remote part of the Nire Valley, County Waterford, but was adjourned on 26 March because of the failure to agree on a common strategy.

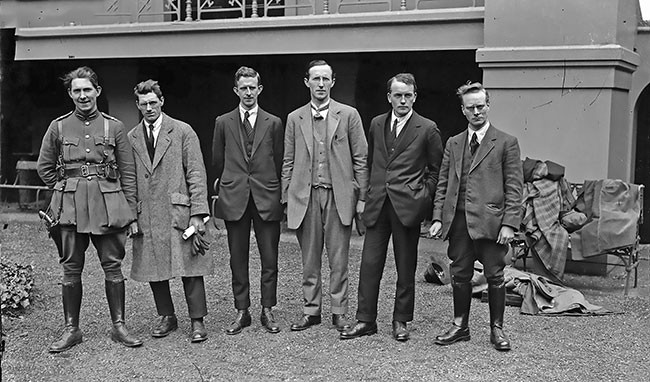

• Seán Mac Eoin, Seán Moylan, Eoin O Duffy, Liam Lynch, Gearóid O Sullivan and Liam Mellows, seen here after a meeting of Pro and Anti-Treaty officers at the Mansion House, Dublin, May 1922

Liam Lynch pressed for a continuation of the struggle. He believed the Free State regime was not willing to negotiate an honourable and realistic end to the Civil War, and the idea of dumping arms was only putting off the struggle for another day. It was agreed that surrender was not an option so it was decided to adjourn the conference for two weeks until 10 April.

Liam Lynch and his comrades arrived in the Newcastle area along the slopes of the Knockmealdown Mountains on the night of 9 April and billeted in farmhouses in the area. Guards were posted all along the routes to the farmhouse and at around 5am Volunteers Ned Looney and Jim Burke. sighted around 60 Free State soldiers under Colonel Tommy Ryan and Captain Tom Taylor advancing towards the Newcastle area. The two Volunteers quickly made their way back to the farmhouses and alerted their comrades.

It was decided to head to Bill Houlihan’s house and assemble there until the Free State troops passed by. Houlihan’s was closest to the mountains. After Lynch and his comrades gathered in the house more scouts arrived to report a second Free State column approaching from the opposite direction towards the Newcastle area. It was decided by Lynch and about a dozen Volunteers to evade the Free State net by cutting across the windswept slopes of the Knockmealdown Mountains.

Two hundred yards up the mountain, as they reached ground with no cover, a second Free State column under Lieutenant Larry Clancy opened fire on the exposed Republican soldiers. Though only armed with side-arms the Volunteers returned fire, but their fire was ineffective against the heavy gunfire from the Staters.

When there was a lull in the fighting they set off but gunfire restarted. Liam Lynch fell to the ground, shot and mortally wounded. His comrades Bill Quirke and Seán Hyde picked up their chief and friend and attempted to carry him across the mountain slopes. But Liam Lynch, realising he was dying and not wanting to slow down his comrades’ escape attempt, ordered that he be left where he was.

All documentation in his possession and his gun were handed over to his comrades. Then, placing a heavy coat over him, they bid farewell. When Lieutenant Clancy reached the spot where Liam Lynch was lying he asked him to identify himself. He replied:

“I am Liam Lynch. Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army. Get me a priest and doctor. I’m dying.”

The Free State soldiers dressed his wound and placed him on a stretcher made from rifles and coats and carried him down the mountain. A priest, Fr Hallinan, arrived on the scene and administrated last rites.

Liam Lynch was then taken to a public house in Newcastle. An ambulance arrived at around 3pm and he was taken to St Joseph’s Hospital in Clonmel. His last words were that he wished to be buried beside his friend Michael Fitzgerald.

Liam Lynch died around 8.45pm on the evening of 10 April 1923, 100 years ago. His death signalled the end of the war and moves were made soon after to conclude that phase of the IRA’s campaign.

•••

To declare a Republic

Gerry Shannon, author of the new biography ‘Liam Lynch - to declare a Republic’, at the recent Dublin launch of the book. Gerry is interviewed by Mícheál Mac Donncha in the current issue of An Phoblacht magazine. The book can be ordered here: liam-lynch-to-declare-a-republic/

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures