12 August 2022

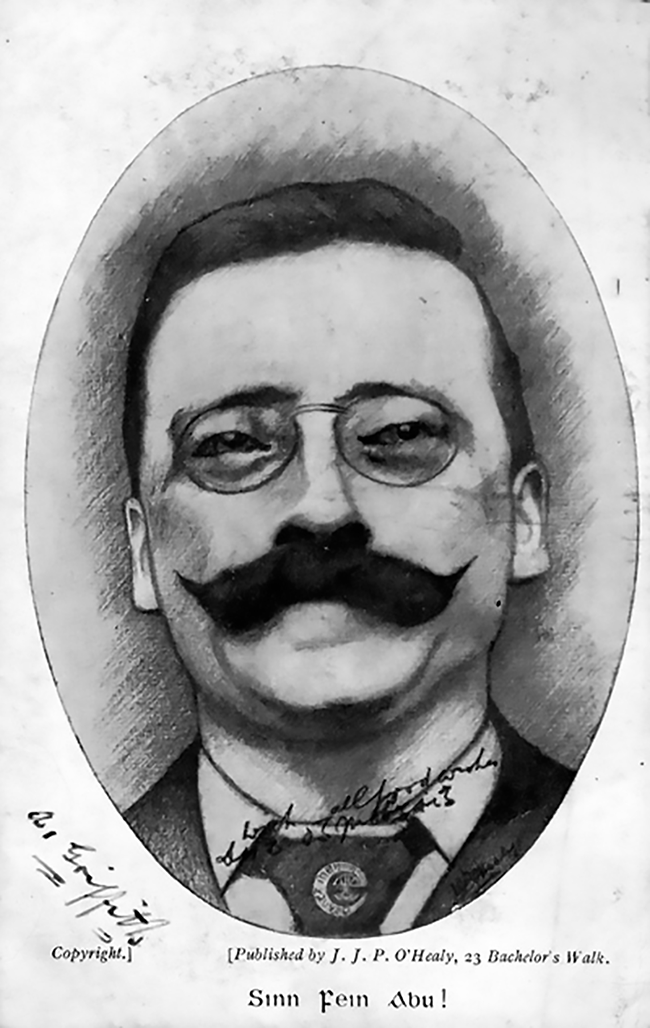

Arthur Griffith: 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922

Remembering the Past - 100 years ago

Arthur Joseph Griffith was born at 61 Upper Dominick Street, Dublin, son of Arthur Charles Griffith, printer, and Mary Whelan. He attended the local Christian Brothers school and began work as an office boy in Franklin Printing at 13. He was a voracious reader and studied for the rest of his years. He was deeply interested in Irish history, culture and language and was a member from his teens of many clubs such as Young Ireland League, the Celtic Literary Society and Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League).

In January 1897 Griffith went to South Africa where he was vocal in his opposition to British rule there and supported the Boers against them. Encouraged home to become editor of the United Irishman when launched in 1898, Griffith was connected with writing and editing a variety of separatist publications for the remainder of his life. He was able to persuade many gifted writers of the time to contribute articles, stories, and poems, but he could be controversial in his views or in what he allowed to go to print, often printing material at odds with the ethos of the newspaper. James Joyce defended Griffith against the complaint that he accepted such contributions: “How do you expect him to fill his paper: he can’t write it all himself.”

A libel action forced the closure of the United Irishman in April 1906 but it was replaced weeks later by his new party’s weekly, Sinn Féin. The newspaper was published daily from August 1909 to January 1910. All the while he was writing pamphlets and contributing to the growing debate about Irish trade, language and sovereignty, republicanism and the First World War. He also wrote ballads including the famous “Twenty men from Dublin town”. To while away the time when imprisoned in Reading Jail in 1916 and again in Gloucester Jail in 1918-19 he produced newspapers to entertain and enlighten his fellow POWs.

It was on 28 November 1905 in the Rotunda in Dublin that Sinn Féin became a political party with Arthur Griffith outlining to delegates his policy of separatism, self-sufficiency and economic independence. While the party grew quite quickly for a number of years, it wasn’t as successful as Griffith and others had hoped. In 1908 Sinn Féin contested the Leitrim North parliamentary seat with Charles Dolan as candidate; he had resigned the seat when he switched from the Irish Parliamentary Party to Sinn Féin, and he was defeated in the election. The party didn’t contest general elections again until 1918, but in 1917 had a series of by-election victories. The party contested local elections but the party was relatively stagnant at this stage with only 128 cumann around the country, whereas after the Rising is burgeoned so that by October 1917 it had 1,200 cumainn.

Griffith advocated a dual monarchy in his famous The Resurrection of Hungary (5,000 copies sold on first day) as a step away from the dominance of London towards a compromise between separatism and Home Rule, having a common sovereign but two independent parliaments. He also argued that Irish MPs should withdraw from Westminster and establish an independent Irish parliament in Dublin. Republicans within Sinn Féin were uncomfortable with Griffith’s dual monarchy policy and urged for a more republican policy. That was not to be until 1917.

Griffith married Maud Sheehan in 1910 and they later had two children, Nevin and Ita. Friends and supporters bought him a house to allow him to concentrate on the party, and writing and editing his newspapers.

Griffith was heavily criticised for his hostility to Jim Larkin and the ITGWU during the 1913 Lockout. While in his newspapers he had denounced slum landlords, bad employers and political corruption, Griffith accused Larkin of misleading workers who were fighting these same forces. Other separatists in or close to Sinn Féin, including Pádraig Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt and Thomas Ashe, strongly disagreed with Griffith and supported the locked out workers.

Griffith joined the newly founded Irish Volunteers in 1913. He was in Howth when the Volunteers landed their weapons in July 1914. A few months later his Sinn Féin newspaper was banned with the outbreak of the First World War, only to be replaced by his imaginative Scissors and Paste which was closed down ten weeks later. June 1915 saw him publish Nationality which continued until the 1916 Rising, and again from February 1917 until it too was banned in September 1919.

On Easter Saturday 1916 he was one of those who carried Eoin Mac Néill’s countermanding order to Irish Volunteer units. When the Rising began on Easter Monday Griffith went to the GPO and offered to join in the fight, but was sent home by Seán MacDiarmada as “they wanted his pen and his brain to survive the fight for their memory - and not to join in”.

He was arrested and interned, firstly in Richmond Barracks in Dublin, before being transported with 1,800 or so other internees to England or Wales, where he was imprisoned in Reading Jail until his release at Christmas 1916.

He threw himself back into politics and was one of those central to Count Plunkett’s victory in the Roscommon North by-election in February 1917.

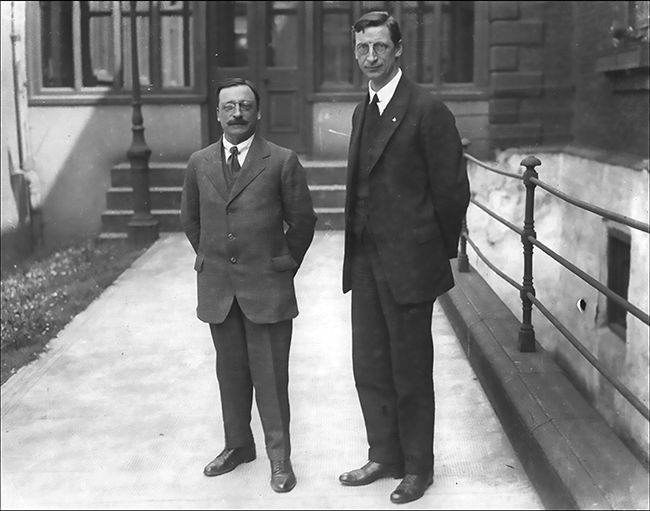

Sinn Féin was growing rapidly. The demand also grew for an openly republican political movement – either a changed Sinn Féin or a new organisation. Four by-election victories: Plunkett (February) , McGuinness (May), de Valera (July) and Cosgrave (August); the death on hunger-strike of Thomas Ashe on 25 September; saw republicans pull together and a compromise was reached. With Arthur Griffith’s reluctant agreement the 25 October 1917 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis adopted a new republican constitution and Arthur Griffith stood back as president in favour of the agreed candidate, Eamon de Valera. Griffith was elected vice-president, a position he was to hold till December 1921. His preferred policy of abstentionism was adopted and his small party had grown to be the most vibrant on the island with 120,000 members and 1,200 cumainn.

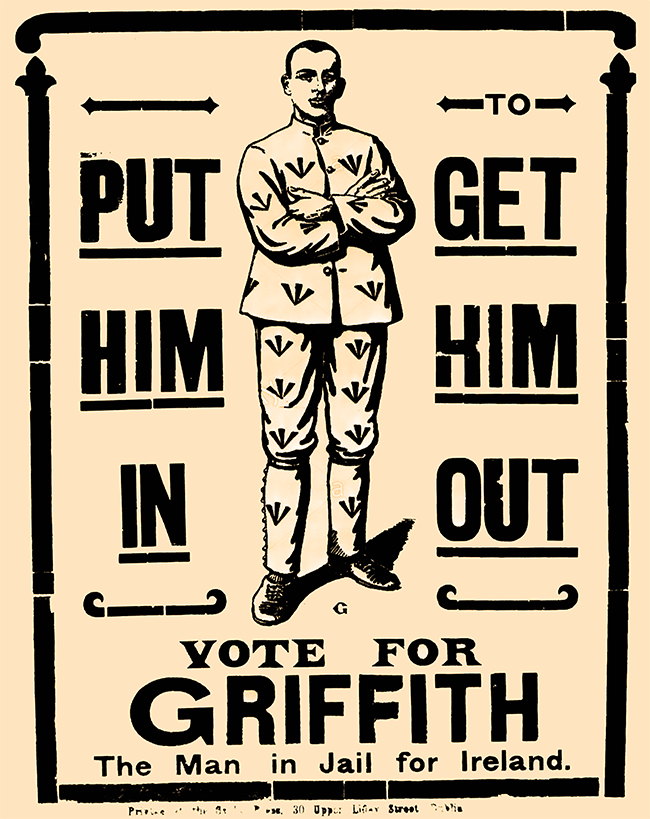

Griffith was to the fore in the campaign against England’s attempt to conscript young Irishmen into the British army and he was the Sinn Féin representative at the anti-conscription conference in April 1918. At this time also he was nominated to contest the vacant Cavan East seat. Before the by-election, he was arrested along with another 72 other Sinn Féin members as part of the England’s contrived German Plot round-up. In June 1918 he was elected by 3,785 votes to 2,581, but he was to remain in Gloucester jail till March 1919. He was re-elected in December 1918 unopposed for the Cavan East seat and also elected to represent Tyrone North-West, where he beat the unionist candidate William Thomas Millar 10,422 to 7,696.

Though An Chéad Dáil Éireann owed a lot to Arthur Griffith’s espousal of the abstentionist policy of Sinn Féin, he was still imprisoned on the opening day, when the majority of elected members of parliament declared Independence from England on 21 January 1919.

He was released on 6 March 1919 along with the other internees and returned to Ireland. In April he was appointed Minister for Home Affairs and when Eamon de Valera travelled to the USA in June of that year he became acting president until he was once again arrested on 26 November 1920. He was to spend the next seven months in Mountjoy Jail.

While Griffith believed independence could be achieved by political methods, he was not a pacifist. Later in the Dáil he supported Cathal Brugha’s proposal that all IRA members should swear an oath of allegiance to the Dáil and that the Dáil should have control over the Army.

In the elections in May 1921 Griffith headed the poll in the Fermanagh-Tyrone constituency and was also elected unopposed for Cavan. He wasn’t released from jail until 30 June and shortly after that was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs, and then appointed by de Valera to lead the Irish delegation for negotiations in London. The three cabinet members Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins and Robert Barton were instructed that the cabinet was to have final say before any agreement was signed.

• Those connected with the signing of the Treaty and later the founding of the Irish Free State: Arthur Griffith, EJ Duggan, Michael Collins, Robert Barton. Standing in the middle Gavin Duffy and two secretaries.

Despite having agreed to submit any final draft to Dublin before signing, Griffith and Collins signed the Treaty without reference back. Griffith had given a personal undertaking to British Prime Minister Lloyd George which the latter used to pressurise him, as well as threatening an immediate resumption of war.

Griffith was the foremost defender of the Treaty in the Dáil debates which followed. The Treaty was passed by the Dáil by 64 votes to 57. Arthur Griffith was then elected President, replacing de Valera, and he formed a new government.

• Arthur Griffith and Éamon de Valera

Griffith worked relentlessly to establish the Free State and he railed against the Republicans who rejected the Treaty. He disagreed with the election pact between de Valera and Collins in June 1922 which put forward a Sinn Féin panel of candidates, reflecting the existing positions on the Treaty, in order to prevent a deeper split. But Collins repudiated the pact on the eve of the election and Griffith deliberately held back publication of the draft Free State constitution until the morning of the poll. This saw an increased number of pro-Treaty TDs and Griffith then increased his pressure on Michael Collins to use the Free State military against Republican forces in garrisons around the country. The Civil War began when Collins ordered the Free State army to bombard the IRA in the Four Courts, using borrowed British artillery. Griffith died on 12 August 1922. A massive funeral to Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin saw all swathes of opinion attend.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures