7 August 2023

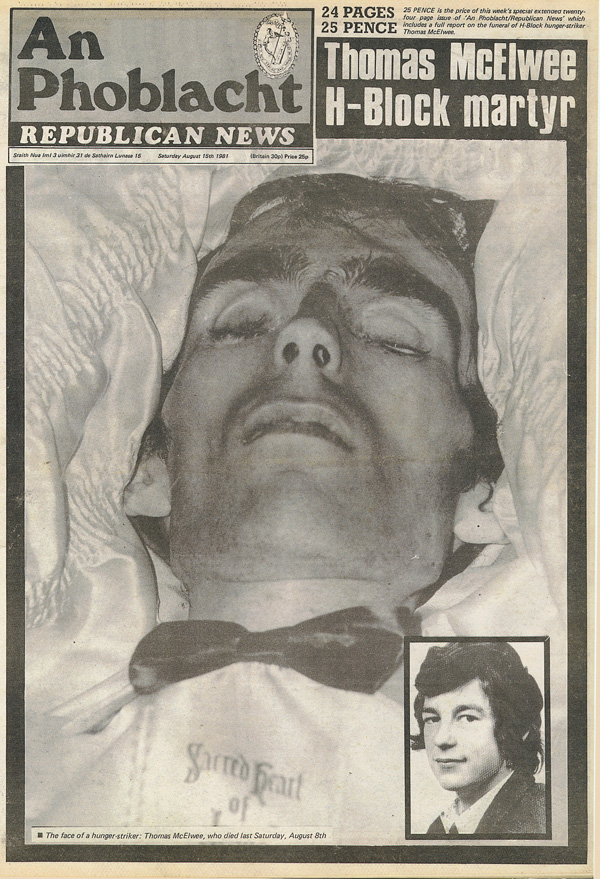

Thomas McElwee – Died on 8 August 1981 after 62 days on hunger strike in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh

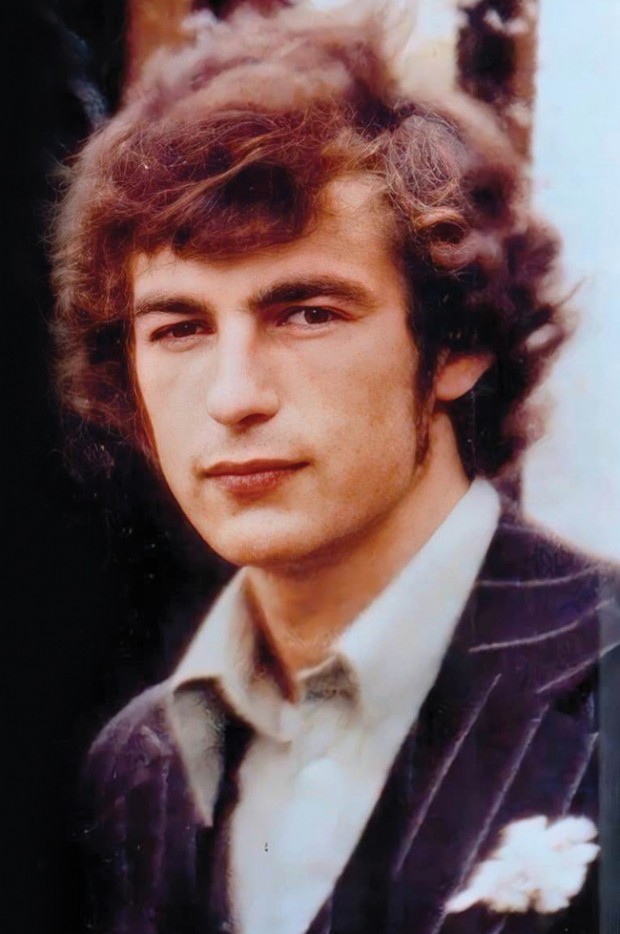

THOMAS McELWEE, aged 23, was born in Bellaghy, south Derry, on 30 November 1957.

Thomas was arrested following a premature explosion in an IRA operation in October 1976 in which he lost the sight of one eye. His younger brother, Benedict, was arrested in the same incident. Thomas received a 20-year sentence in September 1977.

He spent 62 days on hunger strike from 8 June. He died on 8 August 1981.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The death of Thomas McElwee

• Thomas McElwee’s eight sisters – Kathleen, Mary, Bernadette, Annie, Enda, Nora, Pauline and Majella – carry the coffin of their brother

Thomas McElwee, at the age of 23, was the tenth man to join the 1981 Hunger Strike. From Bellaghy in south Derry, he was imprisoned in 1976 after a premature bomb explosion in which he lost an eye.

Thomas was a cousin of another hunger striker, Francis Hughes, also from Bellaghy. They had been boyhood friends, both going on to join the IRA. On 10 August 1981, for the second time, Bellaghy was visited by thousands of mourners gathered to pay their respects to a deceased Hunger Striker.

McElwee died on 8 August on the 62nd day of his fast. Francis Hughes had died three months earlier, on 12 May.

The RUC and British Army converged on the roads around Bellaghy and six British Army helicopters hovered overhead. Thomas’s brother, Benedict, had been denied a visit with his brother the previous week and was then callously asked to identify the body when he died.

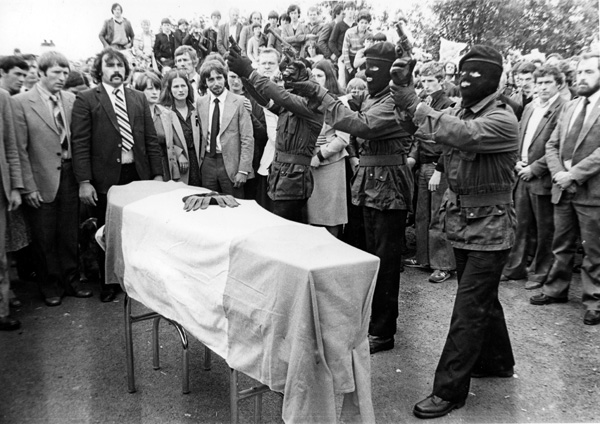

IRA and Cumann na mBan guards of honour lined the path to the McElwee home as the coffin was carried out by his eight sisters. A volley of shots was fired as the cortege reached the road. The crowd in the fields and hillsides cheered as the firing party disappeared out of range of the British crown forces.

Two pipers led the cortege along the five-mile route to the church for Requiem Mass. Thomas’s brother, Benedict, was allowed 10 hours parole for the funeral. In another instance of church interference in the Hunger Strike, the priest at the Mass in Bellaghy Parish Church criticised the Hunger Strikers and called for an end to the fast. Some women in the congregation got up and walked out, disgusted that the priest would use the pulpit on such a tragic occasion to deliver an insulting political speech.

Thomas McElwee’s dying wish was to be buried beside Francis Hughes.

The graveside oration was given by Danny Morrison, then Sinn Féin Director of Publicity.

Thomas McElwee has been described by friends as being “sincere, easy-going and full of fun”. He was also intelligent and determined, something Morrison captured in his remarks on the young Volunteer:

“I know that the McElwee family will understand, just as the families of other dead Hunger Strikers will know what I mean, when I say that their son was invincible from beginning to end, in life as well as in death.”

• IRA Volunteers prepare to fire a volley of shots over the coffin of Thomas McElwee

Morrison went on to criticise the Catholic Church and the SDLP for cultivating defeatism throughout the Hunger Strike rather than pressurising the British Government to come to a just resolution of the protest. He referred back to the sermon delivered earlier at Thomas’s Requiem Mass.

“Those of you who were able to hear Fr Flanagan’s sermon today will have been struck by what is wrong with the Church’s politics. We were asked to pray for an end to the Hunger Strike, for an end to violence and for peace,” he remarked, adding that certainly people should pray for those things. “But there is a bigger prayer which we have to make, and that is a prayer for an end to the cause of violence: the British occupation of our country. It is time the Church prayed and called for that.”

In his oration, Morrison also called for decisive and effective action at ambassadorial and international levels on the part of the Irish Government, who, he said “like many other influential bodies in Ireland which represent the vested interests, have not got the welfare of the prisoners at heart and would quite frankly like to see the hunger strike collapse”.

Morrison also noted and condemned the increasing tendency at the time to blame the republican leadership for the crisis.

“For some time now it has been open season for apportioning blame for the continuation of the Hunger Strike on the leadership of the Republican Movement.” This was, he said, just a variation of former Secretary of State Roy Mason’s theme in 1976 and 1977, in which the implication was that those on the outside had forced the prisoners onto the Blanket Protest.

Identifying the real cause of the problem, Morrison said:

“The roots of the Hunger Strike were built into the British H-Blocks, into the British policy of criminalisation which forced the men on the Blanket five years ago and which led ultimately to republicans resorting to the traditional weapon of hunger strike as the ultimate means of gaining their demands.”

Nor was Danny in any doubt as to the continued determination of the republican POWs in the H-Blocks.

“Their determination has not waned,” he said, stressing that neither should their supporters on the outside lose resolve. “Despair is easy, our enemies want us to despair; to struggle on is a harder task but the reward is there at the end of the road – and Thomas McElwee will be proud of us, as we are proud of him, if we play our full part in winning this prison struggle, in winning, as he set out to win, Irish freedom from the ruins of British rule.”

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures