5 August 2022

A Republican story of women in struggle

Women have a long and proud record in the story of Ireland’s resistance to occupation. That role was not sufficiently acknowledged or recorded in the past. Women have been involved in every stage of the long struggle for sovereignty and independence. That is why Síle Darragh’s book about her years in Armagh prison is an important addition to our recent republican story. These women walk in the footsteps of Charlotte Despard, Constance Markievicz, Síle Humphries, Margaret Skinnider, Kathleen Clarke, Winifred Carney and very many more.

The three main political forces of the day, the Independence Movement, the Labour Movement and the Women’s Movement were now agitating for change and women were involved in all three.

Síle notes, as Gerry Adams did in his foreword to the original book, that the part played by women prisoners in the struggle against criminalisation was not as widely known as it should have been. This book goes a long way to redress that.

It has also an important wider function. It essentially sets her story in the context of the consequences of colonisation on the whole of Ireland and the treatment of communities like hers throughout the Six-County state after partition. It explains why there was resistance to that sectarian state since its imposition by “ordinary people like me”.

• Síle Darragh

In her opening chapter, Síle describes her arrest on August 4th1976 and the charges that sent her to Armagh prison for 5 years. She closes the chapter with the words:

“I was four months shy of my 19th birthday and had been an active member of the IRA for almost three years.”

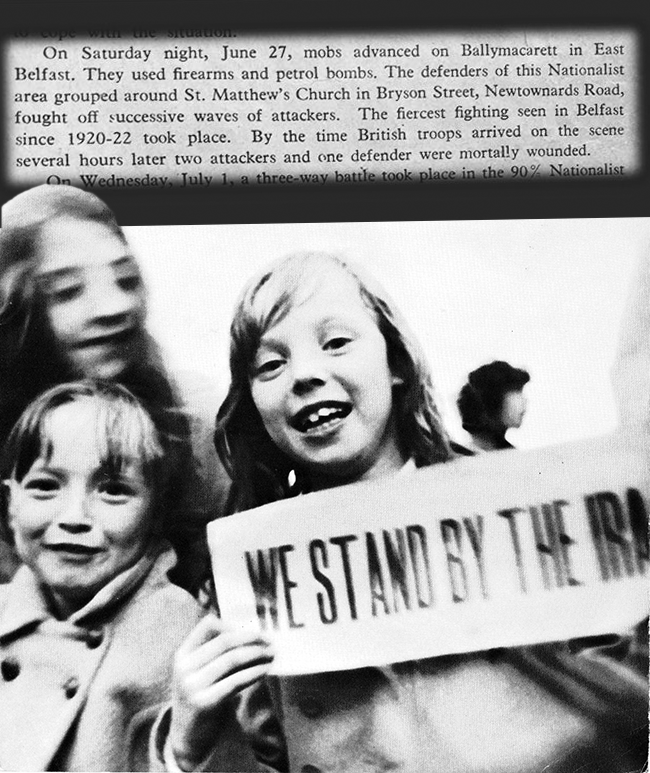

Many IRA Volunteers joined for the same reasons as Síle outlines in the chapter Siege of Ballymacarrett: Ireland’s history of occupation, family involvement, their own life experiences shaped by where they lived, seeing the reality of the institutionalised sectarianism of the Orange State and witnessing the attacks on their families and neighbours.

“My road to the IRA”, she writes,” had begun some six years earlier, on the evening of 27th of June 1970.”

The area was under prolonged attack by armed loyalists firing indiscriminately into the small streets of closely packed houses and residents were trapped in their homes.

A figure appeared in the middle of the street, raised a gun and started firing over the rooftops in the direction of the shots that were pinning them down. Síle, her sister and their father ran to a neighbour’s house that was out of the firing line. The house was full of people, mainly women.

Later that night, watching the flames rise from the firebombed church building, Síle asked her brother -in-law who the person was who had fired the shots to give them cover to escape. He simply said “the IRA.”

Síle writes of her realisation that night that the IRA” were not some mysterious group. They were all around me. They were people I knew, men and women, old and young, who I met daily; family, friends and neighbours, people whose homes I had been made welcome in throughout my life. They were the people of the community; ordinary people like me.”

That paragraph sums up the connection the IRA had with the communities they lived in. It was what sustained them and what would sustain Síle and the other prisoners during the years ahead. Some of those women in that house could have been the mothers, sisters, aunts of the Volunteers defending Ballymacarrett that night, some may have been Volunteers themselves. Women were the backbone of these communities in so many ways. They were strong and resilient women.

That strength was to be tested to the full in later years.

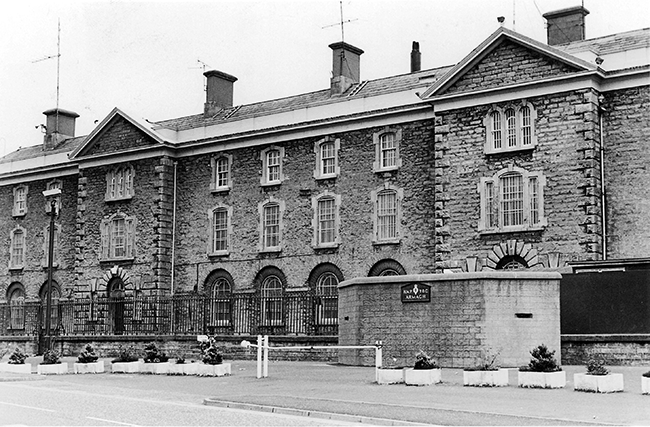

• Armagh prison

A year before Síle arrived in Armagh Prison, the British Government removed political status from anyone sentenced after 1975. It was part of a policy of criminalization of the prisoners and therefore of the IRA and the struggle itself. The protest for political status began.

It would impact hugely on the women in Armagh, and they would impact on it.

Reading this book, it is easy to forget that these were very young women. Most remand prisoners were in their late teens. Síle portrays that well, saying “Although we never forgot we were republican prisoners of war and behaved with a discipline the other prisoners never had, we were still just normal young women with the same interests as our peers.”

• (left to right) Eileen Morgan Sinéad Moore, Maréad Farrell (back) and Síle Darragh, Armagh Jail yard, 1980

As well as the loss of freedom and the poor conditions, many of these young women faced long sentences with the prospect of their fertile years passing while they were imprisoned. They were prepared to take the risk of not having children. It was a huge sacrifice for them to make.

Everything was shared. Clothes, art materials, news from outside from letters and visits. They were locked up but had constant communication via family and friends. Support was a given, between the women themselves, from the outside and from their comrades in the H Blocks.

They came from all over Ireland, the majority from the six northern counties and from all walks of life. That all Ireland network connecting the prisoners with their families and friends and communities was an essential part of the struggle. Republican women were the mainstay of it.

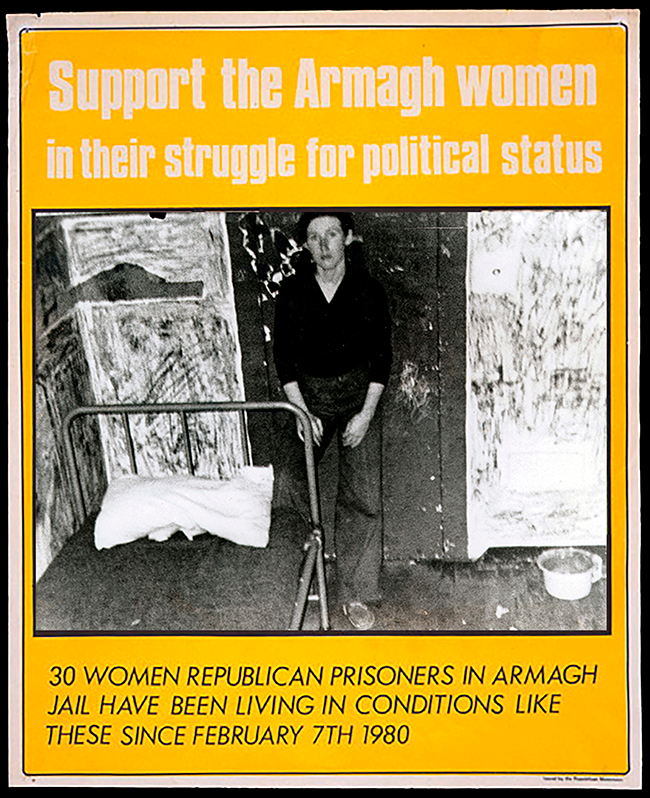

The policy of criminalization escalated in February 1980. Locked in their cells, access to toilet and washing facilities denied, the prisoners decided that they had no alternative but to go on a no wash protest. This was a hard decision. Women were particularly at risk of infection in the conditions that would arise in the prison.

• Mairéad Farrell on 'no wash protest' in Armagh

Moved to B Wing, they found that the suicide wire between the tiers had sheets of plywood nailed over it so no natural light got to the lower level. There was worse to come, the cell windows had been boarded up too.

“And there we stayed, in semi darkness and surrounded by our own filth, for a year”

The no wash protest in Armagh brought renewed attention to the protest and a dilemma for the Irish Women’s Movement. It had largely silenced itself as a movement on the north and the treatment of women prisoners. The national question and anything associated with it was taboo. But the women did have the active support of Women against Imperialism and women from Troops Out in England who tried to get the established women’s groups to raise their voices against the treatment of the Armagh women.

• Support for the Armagh POWs

The demonstrations outside the prison on International Women’s Day brought women from Britain, Europe and the US to join the demonstration but not the established Irish Women’s group.

A turning point came when the indomitable Nell McCafferty wrote a searing article for the Irish Times on August 22nd1980.

Headlined “It is my belief that Armagh is a feminist issue”, she wrote, “There is menstrual blood on the walls of Armagh Prison ---the 32 women on dirt strike there have not washed their bodies since February 8th1980.” Nell described in stark terms what the conditions were in Armagh. She challenged Irish feminists with the words “The choice for feminists on the matter of Armagh jail are clear cut. We can ignore these women, or we can express concern about them. The menstrual blood on the walls of Armagh prison stinks to high heaven, shall we turn our noses up?”

• Exercise yard in Armagh, 1980

Censorship also played a huge part in the lack of knowledge and understanding of what was happening in the North. The notorious Section 31 had been imposed by the Irish government in 1971 to silence anyone “risking the security of the State.” Censorship lasted all of 30 years despite the courageous opposition of some journalists.

Nell’s article caused furore. Letters poured into the Irish Times and as Nell intended, sparked a debate in the Women’s Movement that could not be suppressed. Some women still justified their stance of ignoring or indeed condemning the Armagh women. But it did bring a renewed public focus on the whole issue of the treatment of republican prisoners including the women in Armagh.

More women joined the International Women’s Day protests which got some publicity and gave great heart to the prisoners. Protests at British Embassies around the world were an embarrassment to that Government but still Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refused to do anything to ameliorate the situation.

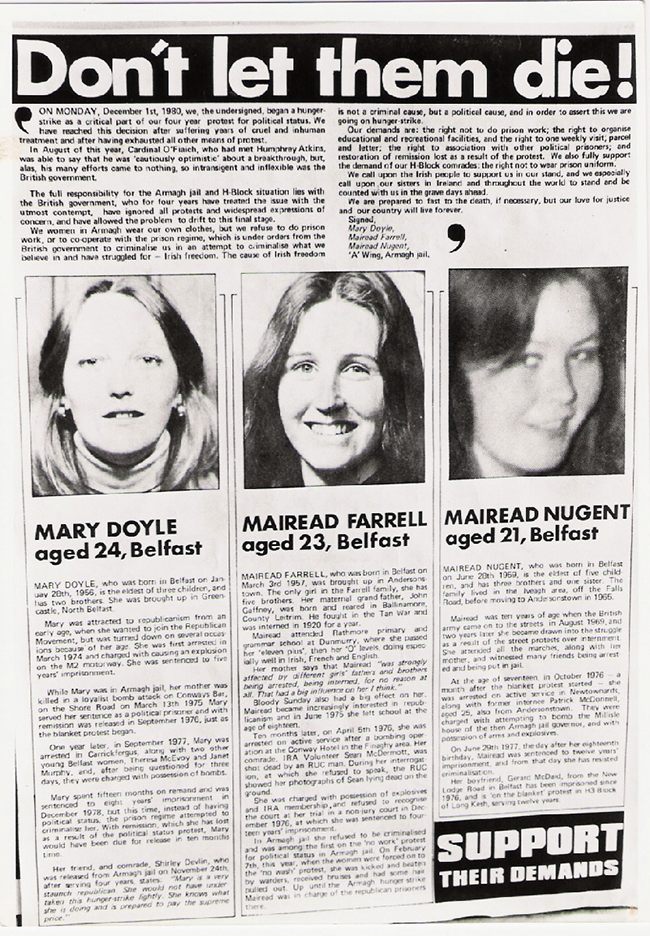

The impasse had to be broken. Talk of hunger-strike increased. The prisoners, women and men, felt they had nothing left to fight with. Comms between the OC of Armagh Mairead Farrell and the OC of the H-Blocks Brendan Hughes were concentrated on that one question, Hunger strike.

Would the Movement outside back their decision? Without outside support it would not work.

And it needed huge support.

Would women join a Hunger Strike, how many, what were the consequences for them? To be weakened by hunger-strike in the infection prone environment of the prison carried added peril for women.

On October 27th1980 seven men went on Hunger strike in the H Blocks.

The statement from the women who would go on hunger-strike was released on December 1st.They were Mary Doyle, Margaret Nugent and Mairead Farrell. Mairead had to step down as OC and her place was taken by Síle. She was 23 years old. Bobby Sands was OC in the H-blocks as Brendan Hughes was on the Hunger-strike. The comradeship and mutual respect between the prisoners was remarkable including that between the H-Block prisoners and the Armagh women.

The news of the ending of the H-Block hunger strike came to Síle on December 18th via the small radio that had been smuggled in. Unknown to her, Danny Morrison had been trying to get in to tell her what had happened and had been refused. That was an act of petty cruelty, leaving the women affected to suffer for another long day without the information that the Hunger -strike in the H-blocks had ended.

The decision was made to end it in Armagh.

But there was worse to come and Síle and the other women knew it. The spectre rose quickly of another hunger-strike.

Síle and Mairead were aware of the feelings of the other women prisoners, they would not give in.

But the risks associated with another hunger strike in Armagh were too great.

• Bobby Sands

On March 3rd Síle got her last comm from Bobby Sands. He tells her of the H-Block prisoners admiration for the women’s bravery. He does not mention a second hunger strike but it is clear he had committed to it. He knew he would die and Síle knew it too.

The rest of her sentence was spent organizing a campaign of letters and messages from the women prisoners appealing for support for the protests. They were smuggled out on visits and sent out across the world. Great hope of a breakthrough arose when Bobby Sands won the MP seat in Fermanagh/South Tyrone made vacant by the death of Frank Maguire. But even that did not move the British government.

Síle was released on August 5th. Eight of the hunger strikers had died. Mairead Farrell with whom she had shared so much responsibility, walked her to the gate. All the other prisoners came out on the wing to say goodbye. She was leaving friends that she had shared so much with for five years.

Síle went back to the struggle as did many women prisoners. Her friend Mairead died in a hail of bullets in Gibraltar two years after her release. She had served 10 years.

I am extremely moved by this book and the powerfully evocative story Síle tells of the courage and endurance of these women prisoners and the many who came after them. They were an essential, equal and valued part of this long fight for independence.

John Lennon’s Dead Stories of Protest, Hunger Strikes and Resistance is published by Beyond the Pale books priced £10.

Available from Sinn Féin Bookshop >

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures