7 June 2022

Anti-Irishness has never really gone away in Britain

“Some people watching might think: ‘well, that’s not an altogether nice term’…”, so posited the BBC’s Huw Edwards while commentating over the annual ‘Trooping the Colour’ ceremony on Thursday this week.

Throughout the broadcast, his co-commentator Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton had repeatedly referred to the Irish Guards - his own former-regiment - by their nickname: ‘the Micks.’

Edwards quickly provided cover for Lowther-Pinkerton, however, adding “… but it is worth underlining that it’s what you Irish Guards call yourself.” Lowther-Pinkerton, unsurprisingly, concurred. Summarising, “it has been our nickname for so long that any connotations that may or may not have been have worn off.”

In earlier remarks Lowther-Pinkerton had praised how: “The Micks have this fantastic mix of guard’s discipline and pursuit of excellence - with their Irish ‘irrational tenth’, if I can quote Lawrence of Arabia.”

Such commentary was not surprising. A ‘Trooping the Colour’ ceremony is not an occasion for reflection or contrition. Indeed, it’s probably the last place where you would expect to find such concepts.

The messaging, symbolism, and intent behind the spectacle was an amplification of British nationalist bombast and popular nostalgia for the days of Empire. The entire affair represents a vestige of a fabled era when Britannia ‘ruled the waves’ and all was supposedly well with the world.

Subtly, nuance, and generosity were in short supply. For whatever it was worth, however, I cut the clip out and uploaded it onto twitter. More as a curiosity than anything else. Personally, the entire exchange had just struck me as a conversation out of time and out of touch. A bizarre throw-back to a time when ‘the Irish’ were most readily understood as mere ‘Micks.’

Defined not as a separate nation but as a domestic stereotype. Recalling a time when the British defined Irishness, rather than the Irish defining themselves. A conception of Irish identity entirely based on its interplay with English identity. A dichotomy that was fundamentally imbalanced given one held power and authority over the other.

The ‘Irish’ were typically presented in British discourse as pesky. Inscrutable. Or, as Lowther-Pinkerton characteristically termed it on Thursday, irrational.

But nonetheless, they could also be amusing and enlightening. But in an accidental way. And on occasion, and particularly when wearing British uniform, brave and loyal.

Anyhow, the clip found an audience. I have since muted the twitter thread it as the phone screen kept flashing, but (at the current time of writing) the 53-second clip has garnered over a million views.

The overwhelming majority who engaged with it heard the same thing that I heard. Many expressed disbelief and incredulity. Many shared their own experience of anti-Irish rhetoric when living in Britain.

Some did not agree. Some did not understand – or did not wish to understand - why people could find offence in what was said. It is fair to say, my ears would be sensitive to such talk of ‘Micks’.

Each of my Grandparents emigrated from Ireland to England in the 1940s/50s. Each had their own story, but all of them spoke of the anti-Irish racism they experienced in Britain. As did my great-aunts and uncles.

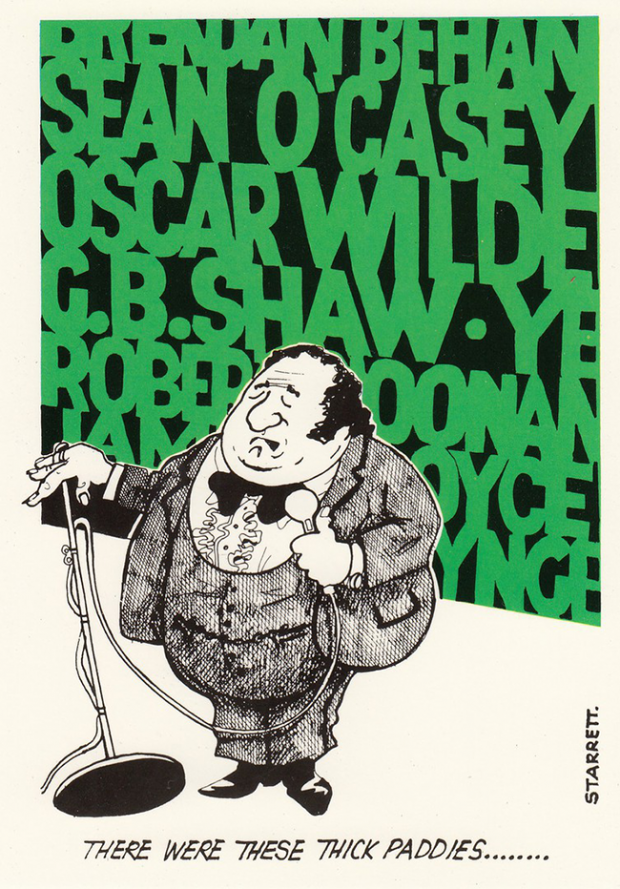

The No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irishsigns. The ‘thick Irishman’ jokes on Saturday night television. Newspaper articles advising English ‘housewives’ not to buy Irish products. Suspicion and hostility from people in authority.

They faced being called a ‘Mick’, a ‘Paddy’, or a ‘Biddy’. As if they had no identity beyond where they came from. Debased, demeaned, and defined as just another one off the boat. My parents had similar experiences growing-up as the children of Irish immigrants in England. Some people might have short memories. But not those who lived through it. And not those of us whom they raised.

And, in truth, anti-Irishness has never really gone away. As time went on, and people settled, other new communities arriving in Britain became the focus of such unpleasant attention. Besides with the commencement of the Irish Peace Process, from the late-1980s onwards, the Irish became less of a live ‘issue.’

In truth, until the Irish in Britain opened their mouths, so-to-speak, they could generally pass and avoid much hostility. And their sons and daughters, raised with English accents, could do so even more easily. But anti-Irishness has always been there, just beneath the surface, and at intervals it resurfaces.

There have been notable cases in recent times. The denial of an Irish tribute on a headstone in Coventry. Priti Patel’s talk of threatening the Irish with ‘food shortages’ during Brexit negotiations. The media furore that surrounds, the footballer, James McClean each-and-every November. A British Holiday Park blacklisting Irish surnames as ‘undesirable’. To cite but a few examples.

Suffice to say the Irish in Britain are fed up with being called ‘Micks’ or ‘Paddies’. Fed up with jokes about ‘potatoes’ or mock accents.

That is why talk of “the Micks” and the “Irish ‘irrational tenth’” rankled with people in such numbers. It’s not that people don’t understand that the Irish Guards is regiment of the British Army that has always been known as ‘the Micks’. We know this. That’s understood.

It’s what that informs us about the conception of Irishness that still prevails in Britain. We know that the Irish Guards is made up of British soldiers from Britain and places beyond Britain. We know that some of those enlisted may even have come from Ireland. North or South. It does not matter. That’s not in dispute.

However, a regiment of the British Army referring to itself as ‘the Micks’, no matter how affectionately or light-heartedly, is offensive. The fact that there’s a regiment within the British Army, in this day-and-age, that essentially ‘play-acts’ as Irish is frankly bizarre.

It is a relic of a past that’s best left in the past. A hangover of imperialism and colonialism. It may have escaped the notice of some, but most of Ireland has long-ago left the supposed ‘United Kingdom.’

And the part of Ireland which still remains under British jurisdiction, for the time being, is somewhere that has long struggled with identity.

It is a part of Ireland where ‘Irishness’ has long been subjugated and denied. Where British identity was deliberately given supremacy.

A place where the Irish flag was not so long ago a proscribed emblem. Where the Irish language has long been discouraged, devalued, and denied. It is an artificially carved-out statelet designed and constituted to deny full Irish nationhood and independence. It is a wound that still needs to be healed.

A British Army regiment co-opting the national symbols and trappings of its nearest neighbour makes little sense in the twenty-first century. If it ever did make any sense at all.

For all the talk of honour and presentation, the ‘Irishness’ of the Irish Guards is hackneyed at best. An Irish Wolfhound for a mascot. Sprigs of shamrock on St Patrick’s Day. Let Erin Remember.

Essentially, what makes the Irish Guards the supposed ‘Irish’ Guards is artifice and mimicry. They’re ‘stage Irish’ in British uniform. ‘Paddywhackery’ in step march. Those who defend the nickname cannot pretend that it isn’t a direct reference to a popular slur for Irish people.

Where does this supposed beloved ‘historic’ nickname come from, if not from a ‘historic’ pejorative for Irish people in Britain? A pejorative which demonstrably isn’t all that historic!

To call any Irish person a ‘Mick’ is bigoted. It is an ignorant label that’s applied to someone from another country. It’s as simple as that. That should be the end of the conversation.

Let’s be honest, if we were to honestly seek to establish whether the ‘connotations’ that lie behind the nickname have ‘worn off’, the last party that would require consultation would be the British Army.

An Army that has murdered, tortured, maimed, and robbed the Irish people for much of its existence. An Army that all too many honest and sincere Irishmen naively signed-up to join. Only to act as cannon fodder for Britain’s foreign wars.

An Army that, to this very day, seeks to defend those who carried out wanton violence in the North of Ireland while wearing British Army uniform. The British Army does not decide what is or isn’t offensive.

You don’t get to play ‘the Mick’ for a laugh. Being ‘a Mick’ is not some kind of affectation or pet-name that can be picked up and dropped.

Not when countless Irish people have had such terms spat at them. People are not prepared to tolerate such nonsense anymore. Some things are best consigned to history.

… l know your streets

aren’t paved with gold

because l laid them,

come rain or cold,

your M1s and your M62s,

reading your B&B cards:

No Blacks, No Irish,

No Dogs, No Jews.

I am the slighted Irish

minding your sick,

teaching your children.

You called me thick…

Excerpt taken from ‘The Trojan Donkey’ edited by Ian Duhig and Teresa O’Driscoll

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures