30 April 2022

The history of May Day

• The Haymarket rally, 4 May 1886

First published: 1 May 2008

• — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — •

Workers of the world, awaken!

Rise in all your splendid might

Take the wealth that you are making,

It belongs to you by right.

No one will for bread be crying

We’ll have freedom, love and health,

When the grand red flag is flying

In the Workers’ Commonwealth.

— Joe Hill

• — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — • — •

WHEN IRISH IMMIGRANTS began arriving in the United States in the mid 19th Century, they found an economy in the midst of an industrial boom. The benefits of that boom, however, were not being reaped by everyone.

Conditions for workers in America, and in fact the rest of the world, were dangerous and exploitative. Men worked long hours for low pay and with few breaks. The situation was worse for women and children who made up a high percentage of the work force in industries like clothing and cleaning and often received but a fraction of the wages a man could earn. Economic crises swept America and were used by employers to further erode industrial wages and depress conditions.

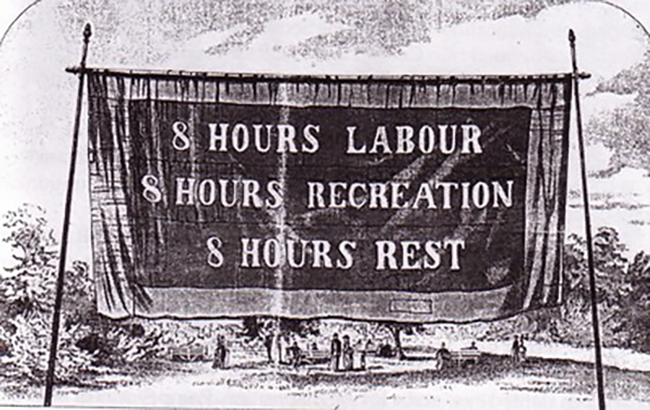

One of the most contentious issues in America’s labour market was the length of the working day. Factory workers could find themselves standing on the floor for 12 hours a day. An international movement for an eight-hour working day had already began to emerge and it wasn’t long before American unions followed suit.

In October 1884, the Federation of Organised Trades and Labour Unions (FOTLU) of the United States and Canada unanimously set 1 May 1886 as the date to demand the eight-hour day. Workers prepared for a general strike in support of the campaign.

• A Federation of Organised Trades and Labour Unions banner: FOTLU set 1 May 1886 as the date to demand the eight-hour day

On the day, rallies were held throughout America with an estimated 10,000 demonstrators in New York and 11,000 in Detroit. Given the fear that workers would have had about mobilising for an event such as this, the numbers which turned out were huge. In Chicago, an estimated 40,000 workers went on strike. Albert Parsons, founder of the International Working People’s Association (IWPA), along with his wife, Lucy, and their children, led a march of 80,000 people.

Two days later, on 3 May, striking workers in Chicago met near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Co plant. A fight broke out when scab replacement workers attempted to cross the picket lines. The police intervened and attacked the strikers. Four workers were killed and several others wounded, sparking outrage.

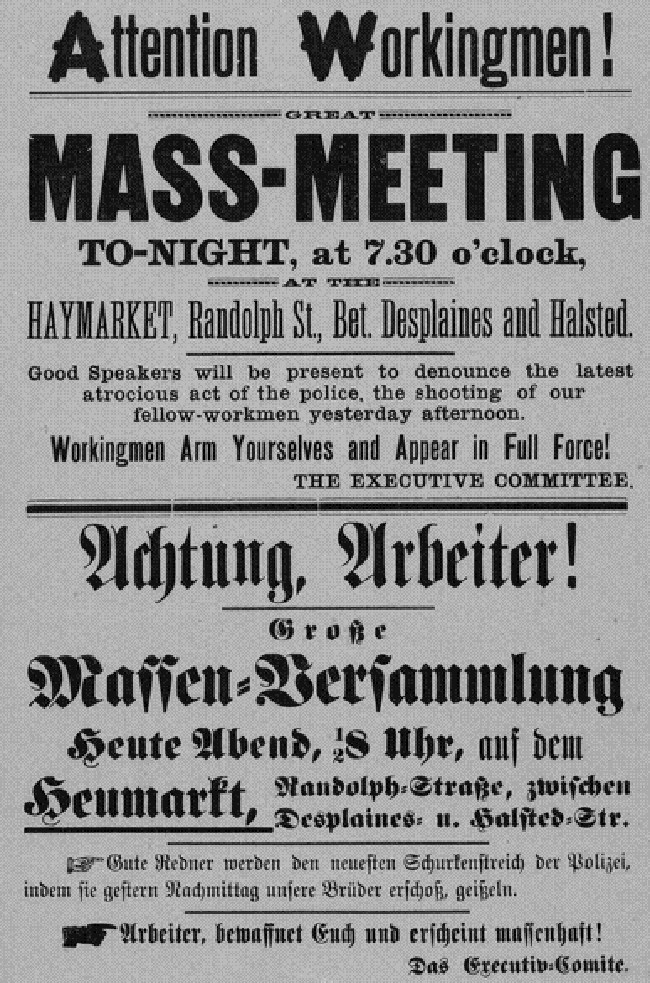

Workers in other areas quickly printed and distributed fliers calling for a rally the following day at Haymarket.

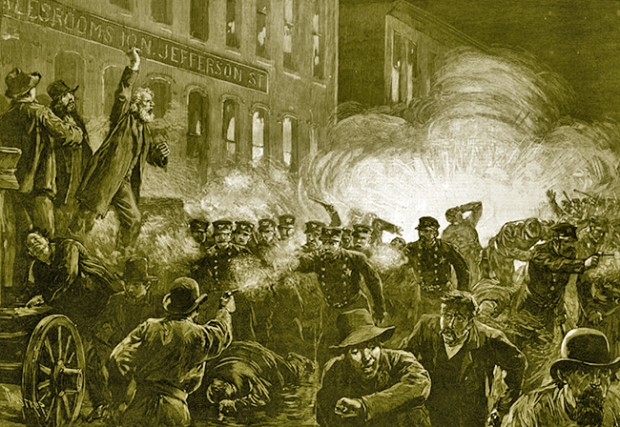

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of 4 May. Labour activist August Spies spoke to the large crowd while standing in an open wagon. Throughout, a large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby. According to witnesses, Spies informed the audience from the start that the rally was not meant to incite violence.

Samuel Fielden, the last speaker, was finishing his speech at about 10:30pm when police ordered the rally to disperse and began marching towards the speakers’ wagon. At that point a bomb was thrown at the police line and exploded. Nobody knew who threw the bomb. The police immediately opened fire. Some workers were armed but accounts vary widely as to how many shot back.

Several police officers were injured by the bomb and one killed, but most of the police casualties were caused by from friendly fire. It is unclear how many civilians were wounded since many were afraid to seek medical attention, fearing arrest.

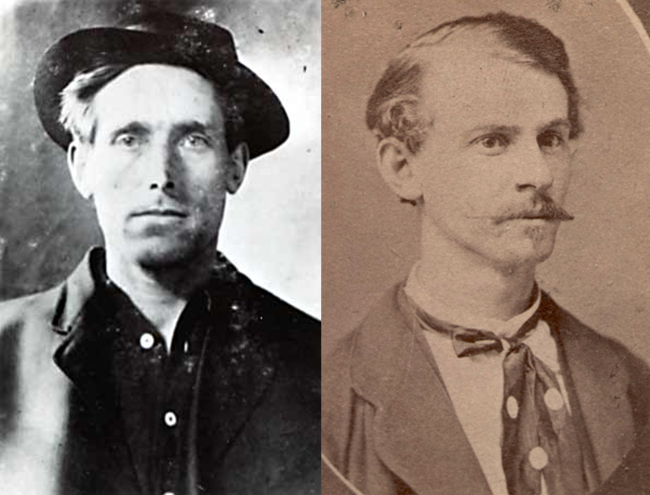

• Joe Hill and Albert Parsons

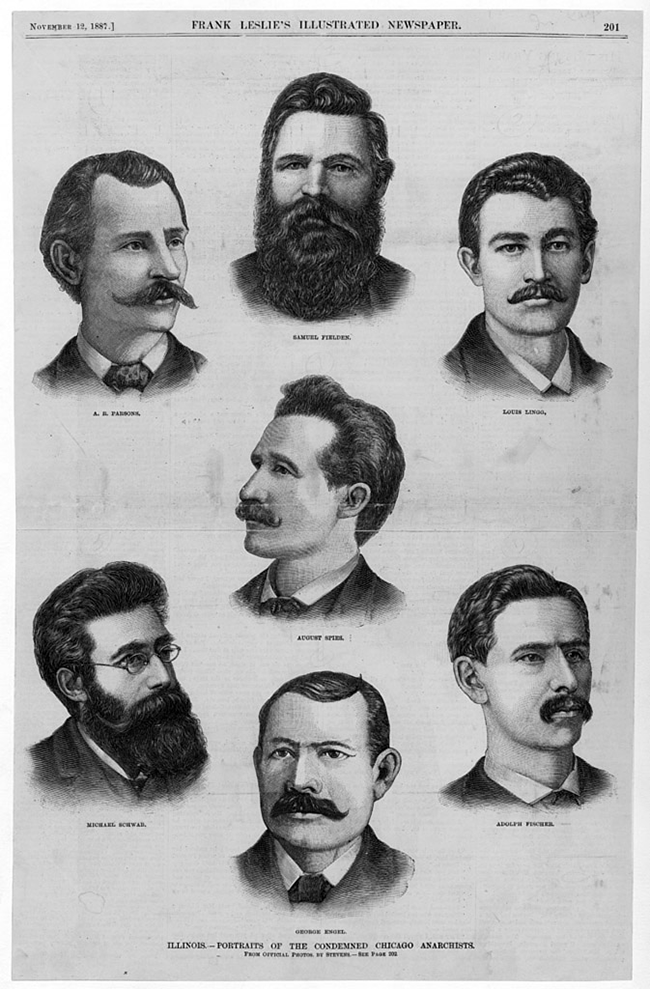

Eight people were arrested afterward in connection with the rally and charged with the murder of the policeman by the bomb: August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Neebe.

Their trial started on 21 June. The prosecution did not offer evidence connecting any of the defendants with the bombing but argued that the person who had thrown the bomb had been encouraged to do so by the defendants, who as conspirators were therefore equally responsible. The defendants claimed there was evidence linking the police to the actual throwing of the bomb in order to incite a riot.

Eventually, the court returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants – death sentences for seven of the men, and a sentence of 15 years in prison for Neebe.

The case was appealed in 1887 to the Supreme Court of Illinois, then to the United States Supreme Court.

After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois Governor Richard James Oglesby commuted Fielden’s and Schwab’s sentences to life in prison. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled dynamite cap which he held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast only blew off half his face and he survived in agony for six hours).

The next day, 11 November 1887, Spies, Parsons, Fischer and Engel were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the Marseillaise, the anthem of the international revolutionary movement. In the moments before the men were hanged, Spies shouted, “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!” Witnesses reported that the condemned did not die when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly.

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Schwab and Neebe were also buried at Waldheim when they died, reuniting the ‘Martyrs’.

The trial has been characterised as one of the most serious miscarriages of justice in United States history. Most working people believed Pinkerton detective agents (a private US security company) provoked the incident.

• Haymarket ‘Martyrs’: Engraving of the seven sentenced (Oscar Neebe, not shown)

In 1893, pardons were signed for Fielden, Neebe and Schwab after an Illinois governor concluded that all eight defendants were innocent. The governor said the real reason for the bombing was the city of Chicago’s failure to hold Pinkerton guards responsible for shooting workers. The pardons ended his political career.

The Haymarket affair was a setback for American labour and its fight for the eight-hour day. At the convention of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1888, the union decided to campaign for it once again. 1 May 1890 was agreed upon as the date on which workers would strike for an eight-hour work day.

America finally got the eight-hour working day in 1938.

May Day — or International Workers’ Day — is still celebrated around the world. It was celebrated in Ireland for the first time in 1891.

The fight for an eight-hour day might have been won but in this state we still don’t have equal pay for women or agency workers. We don’t have legislation protecting workers from corporate manslaughter. We don’t have paid paternity leave. We don’t have a range of rights and entitlements that we should. But, most importantly, we don’t have the right to collective bargaining.

The struggle continues.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures