30 March 2024

The 1916 Proclamation

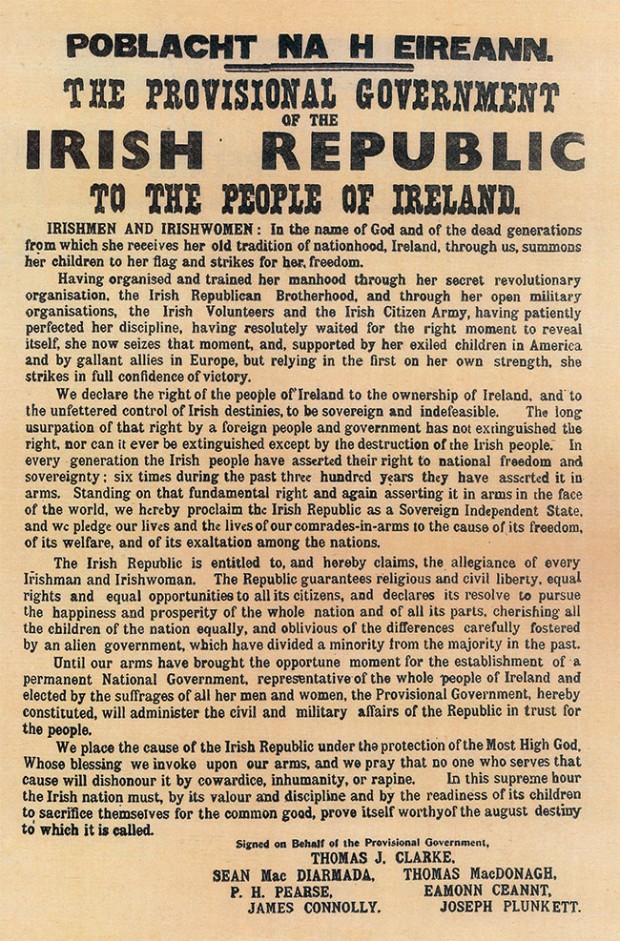

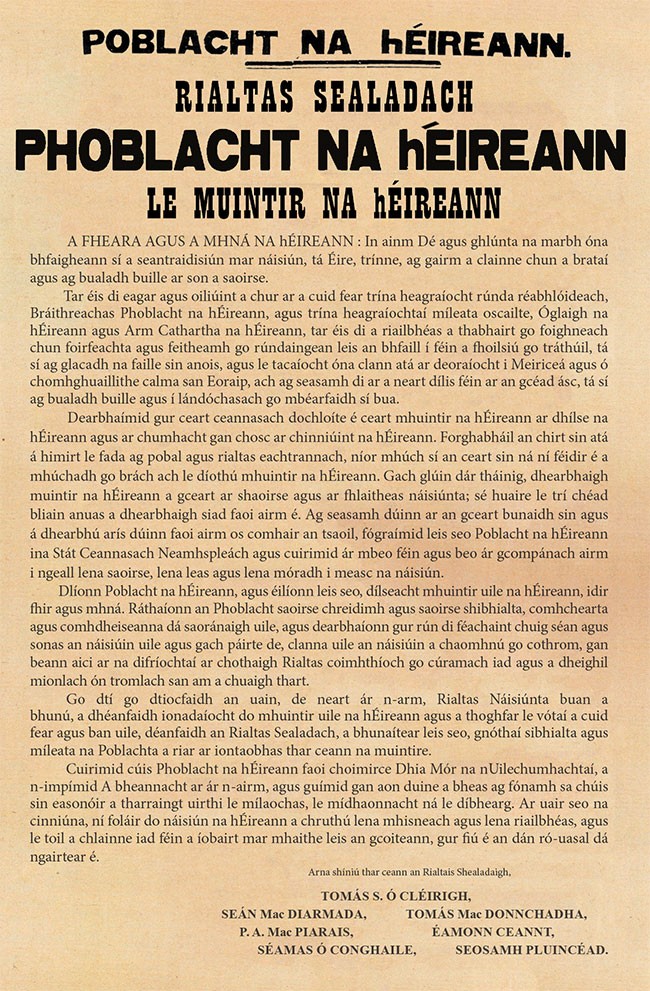

THE 1916 PROCLAMATION, heralding the establishment of an Irish Republic and read by Pádraig Pearse from the steps of the GPO in Dublin at 12 noon on Easter Monday 1916, is undoubtedly one of the most significant documents ever written in Ireland.

It contains the first formal assertion of the Irish Republic as a sovereign independent state. As well as being a Proclamation of independence, it is also a declaration of rights. Moreover, the signatories made good this assertion by force of arms and by pledging their own lives and the lives of their comrades-in-arms to the cause of Irish freedon and the right of its people to a government of their own.

The authors of the Proclamation set out the principles and values on which an Irish Republic should be created and enunciated noble standards to which Irishmen and Irishwomen could rally in the struggle for independence and freedom.

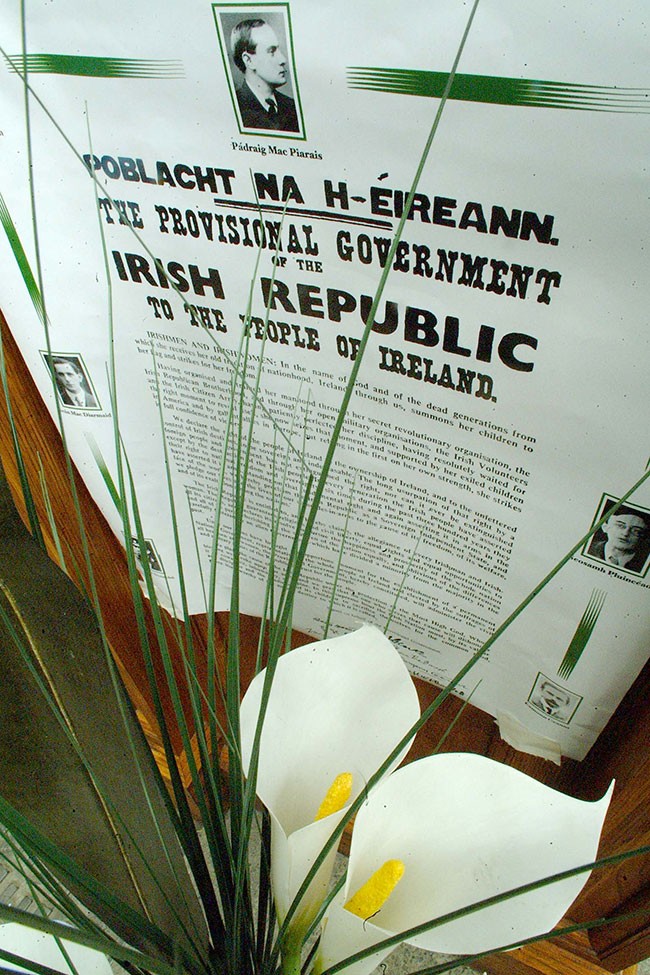

In 1915, a Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (comprising Thomas J. Clarke, Pádraig Pearse, Seán Mac Diarmada, Joseph Plunkett and Éamonn Ceannt) was set up to plan the Rising. In January 1916, Thomas MacDonagh and James Connolly became members. These seven were to become the signatories of the Proclamation.

Throughout 1915, the intensive planning and preparations for the Rising had been proceeding in the greatest secrecy and, in January 1916, the Military Council decided upon the date for the Rising: Easter Sunday, 23 April 1916. An essential element of these plans was the issuing of a founding document proclaiming an independent Irish Republic.

On the Monday prior to Easter Week, the Military Council met to finalise plans for the Rising. A Provisional Government was constituted and the historic Proclamation of the Irish Republic was prepared, calling on the Irish people to pledge their allegiance to the resurgent nation.

By common consent amongst the signatories of the Proclamation, the honour of signing first was given to the unrepentant and uncompromising Fenian, Thomas Clarke.

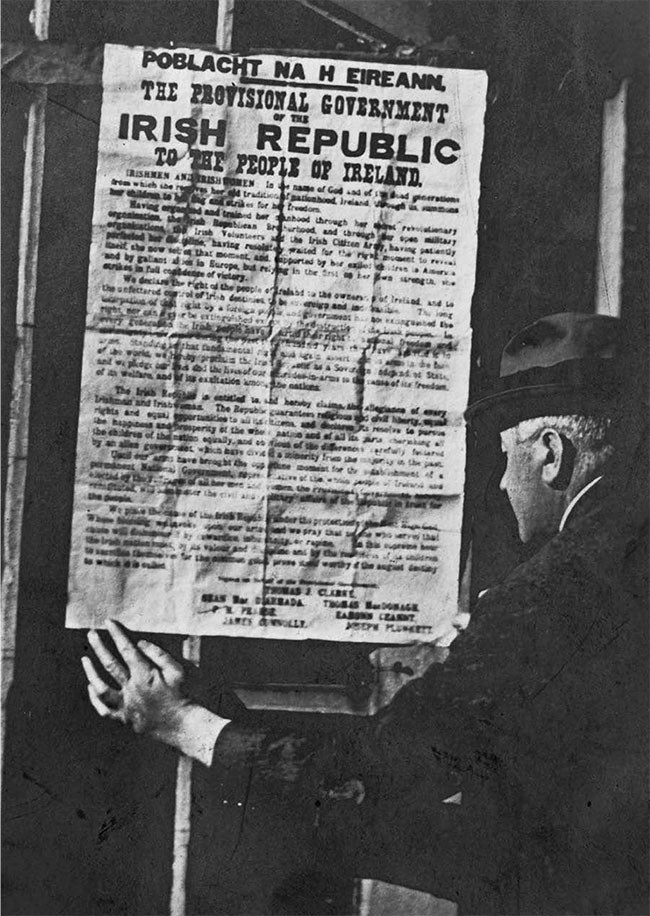

• Dr Edward McWeeney of University College Dublin reads a copy of the Proclamation on Easter Monday, 24 April

That the Proclamation encapsulated the feelings of all seven members of the Military Council is beyond question. Although the actual literary composition of the document is believed to have been mainly the work of Pearse, it also shows the ‘traces of change’ and amendment by Connolly and perhaps MacDonagh. The Proclamation’s assertion of the claims of a sovereign people to social justice and to control of the country’s natural resources shows the influence of Connolly in the drafting of the document.

The final version of the four-page manuscript of the Proclamation was given to MacDonagh for safekeeping until Easter Sunday morning. On that morning, at a meeting of the Military Council in Liberty Hall, it was handed over to Connolly to whom had been assigned the responsibility for having it printed.

Three men – Michael Molloy and Liam O’Brien (compositors) and Christopher Brady (printer) – were selected to undertake the secret task of the printing of the Proclamatlon. All three had spent their spare time helping in the printing of The Workers’ Republic, which was published by the Irish Workers’ Co-operative at Liberty Hall.

The men met Connolly at Liberty Hall at 9am on Easter Sunday, 23 April. On arrival, Molloy, O’Brien and Brady were placed under immediate arrest for their own protection in case the premises were raided by the police, thus affording them the opportunity of pleading working ‘under duress’.

At 11 am, Connolly asked each in turn if they would undertake the task of printing the Proclamation. All three agreed and the document was handed to the men. Within half an hour, the seven signatories added their names.

The machine used for the printing of the Proclamation was an ancient model of a Wharfedale Double Crown printing press which was in a very run-down condition. The rollers, cylinder and blanket were far from satisfactory. Arrangements had been made with a friendly printer, Joseph Stanley of Liffey Street, to supply the type. However, when members of the Citizen Army went to collect the type, they found that the police had raided the printing works and seized practically all of the type. The police had, though, overlooked a limited number of frames of type which were later collected and taken to Liberty Hall.

Connolly instructed the three men to print the Proclamation on the poster-size paper he provided. From their experience of printing The Workers’ Republic, the men felt that there would not be enough type for a job of this size. Additional type, four cases in all, was obtained from a friendly printer in Capel Street but they still didn’t possess sufficient type. They soon reached a solution to their difficulty: half of the Proclamation would be printed and when this had been done all the type used in the upper half would be available and could be used again for the lower half. So it became necessary to print the Proclamation in two sections. Even then, in order to have the job ready in time, the men had to work through Easter Sunday night.

The upper portion of the Proclamation was set up in type and 1,000 copies were printed. Connolly’s initial order was for 2,500 copies but there was not enough paper.

The actual task of printing the Proclamation was a difficult one. The rickety and antiquated machine, working at top speed, proved troublesome and time-consuming, requiring the constant attention and mechanical expertise of Christopher Brady. He also found it difficult to achieve even inking of the type and the rollers refused to maintain an even pressure, resulting in much smudging in parts and faint printing elsewhere. Typographically, there were also other problems, such as the line spaces constantly forcing their way up and having to be repeatedly forced down again. Brady’s achievement in joining the two halves of the Proclamation was not inconsiderable.

Close examination of the original document will reveal examples of ‘doctored’ letters. Because of the acute shortage of certain letters, many had to be substituted; the letter ‘f’ was converted to an ‘e’ with the aid of some sealing wax while some of the letters ‘c’ appear to have been converted to ‘o’.

The paper used for the printing of the Proclamation was purchased by Connolly at Saggart Paper Mills in Dublin. This paper was of poor quality as far as the texture is concerned and was so thin that it tore easily. This partly explains the rarity of original copies of the Proclamation.

When the work of printing the Proclamation was completed, early on Monday morning, the men followed Connolly’s instructions and handed over the 1,000 copies to Helena Molony, who had reported to the Citizen Army at Liberty Hall. She arranged for their transportation to the GPO.

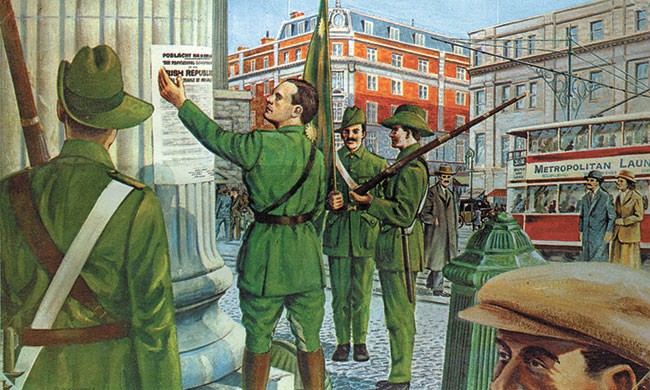

• An artist impression of Pádraig Pearse at the GPO

The Proclamation having been publicly read by Pearse at 12 noon at the GPO, Connolly instructed Seán T. O’Kelly to distribute copies throughout the city of Dublin. Copies were posted on the pillars of the GPO and on shop-fronts in the city centre.

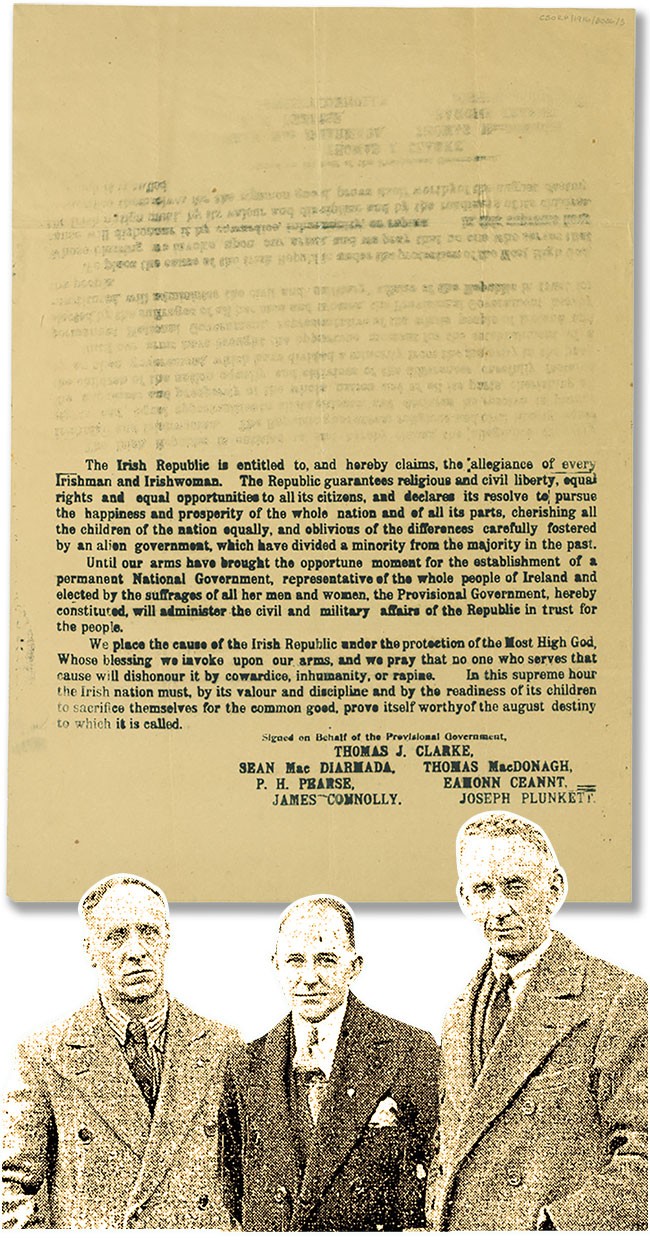

Authentic copies of the 1916 Proclamation are rare documents. Only a few survive, one of which can be seen in the National Museum, Dublin. A genuine copy of the original Proclamation measures 20 x 30 inches, is of poor quality, on off-white poster-type paper, has a variation of spacing between the upper and lower sections, typographical peculiarities and has smudging of certain letters.

• Michael Molloy, Christopher Brady and Liam O’Brien were selected to undertake the secret task of printing the Proclamatlon; Copies of the lower half were printed by British soldiers as souvenirs

Of the original manuscript, the pages from which the printers worked, have unfortunately been lost forever. They were left in Liberty Hall after the work of printing the Proclamation had been completed and were lost in the flames when the building was shelled on Wednesday 26 April by the British gunboat The Helga. The last page, which contained the seven signatories, was taken away by Molloy but while he was being held prisoner in Richmond Barracks he chewed it up into small pieces to dispose of it.

On Wednesday of Easter Week, British soldiers entered Liberty Hall and discovered the old Wharfedale machine in the printing room along with the type used to print the lower half of the Proclamation. The soldiers, unable to locate the cases of type used to print the upper half, and not realising that the Proclamation had been printed in two halves, ran off copies of the lower half as souvenirs and distributed them to their friends and passers-by. A copy of one of these halves is preserved in the Kilmainham Jail Museum in Dublin.

On the first anniversary of the Rising, in April 1917, using the same type as used the previous year, copies of the Proclamation were reissued and posted up throughout the centre of Dublin but very few of these copies are still in existence.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures