25 November 2021 Edition

Recasting the conquest

The Treaty - 100 years on

Recast (verb)

If you recast something, you change it by organising it in a different way. (Collins Dictionary)

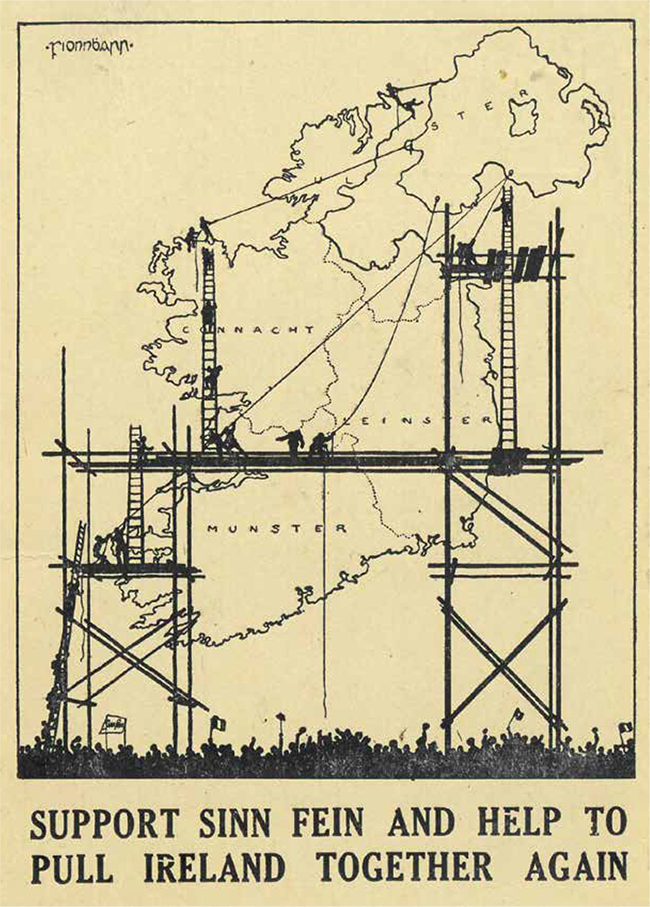

James Connolly called for the reconquest of Ireland by the Irish people. A mighty effort was made to achieve political reconquest between 1916 and 1921 but, 100 years ago, the British government, through a combination of force and fraud, managed to maintain its grip on Ireland and to recast the conquest.

In Ireland today, the debate on the Treaty of 1921 focuses primarily on the Irish protagonists, with relatively little attention paid to the British government side. The perpetual De Valera versus Collins argument predominates. This obscures the fundamental issues involved – Irish Republic versus British Empire, Irish Unity versus Partition, and the cohesion of a political movement versus the personalities and prestige of leaders. And underlying all were economic forces exercising a decisive influence.

The global context needs to be addressed. Britain had emerged victorious from the First World War, but at enormous cost in human life and finances. She was still at the head of her Empire; indeed, she had gained more territory. But subject peoples in India and Egypt and elsewhere were beginning to rise up against British rule. In Britain itself the labour movement was growing and becoming more militant and many looked to the Bolshevik victory in Russia for inspiration.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the British and French sealed their victory. The United States by its entry to the war on their side in 1917 had saved them from defeat by Germany and US President Woodrow Wilson came to Paris in a blaze of glory with his rhetoric of democracy and self-determination for nations. The British and French adopted the rhetoric too - so long as the nations in question were not those subject to their empires. The map of Europe was redrawn with the break-up of the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire and the emergence of new states. Germany was punished, storing up fuel for a future conflagration. And the British and French kept their empires, their ruling classes remaining in place for the time being at least.

In Britain, the Welsh Liberal politician David Lloyd George was the predominant war leader. As Prime Minister, he headed a war coalition of Tory Unionists and Liberals loyal to himself, other Liberals and the growing Labour Party remaining outside. This coalition won the 1918 General Election in Britain - the same election which swept Sinn Féin to victory in Ireland.

• The Irish delegation (from left) Arthur Griffith, Eamonn Duggan, Erskine Childers, Michael Collins, George Gavan Duffy, Robert Barton and John Chartres

The First Dáil Éireann sent envoys to the Paris Peace Conference seeking recognition of Ireland’s right to self-determination. But like envoys from India, Egypt, Indo-China (Viet Nam), and others, they were kept outside the door as the empires shared out the spoils of victory.

1919 ended with the Treaty of Versailles in place and Lloyd George and his government could now give more attention to Ireland. But they had no intention of recognising Dáil Éireann.

Intent on consolidating the Empire, the British government would not countenance the Irish Republic on its doorstep as a dangerous example to other subject peoples. There was a powerful connection between the Tory Unionists in the government and the Ulster Unionists. Together, before the war, they had resisted Home Rule for Ireland, and even threatened civil war in Ireland and Britain if Ulster was to be included under a Home Rule parliament. Out of that confrontation came the concept of the Partition of Ireland, both it and Home Rule being postponed by the war.

The British establishment had been divided over Home Rule but whether they were pro- or anti-, or whatever their position on Partition or, later, on talking to Sinn Féin, they were all imperialists and their priority was to keep Ireland within the British Empire.

To that end, the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries were unleashed on the Irish people in 1920. For the same aim, the Government of Ireland Act of that year was passed, partitioning the country and setting up the Unionist regime in the Six Counties. And it was for the same reason again - to keep Ireland in the Empire - that the decision was made in 1921 to open negotiations with Sinn Féin.

The Irish negotiators were sent as representatives of the Irish Republic. The Dáil and Cabinet which sent them knew that the British would not concede recognition of the Republic. But the mandate of the negotiators was to secure the substance of Irish independence and unity, with the flexibility to provide guarantees for the Unionist minority and for British security. The British government’s insistence on inclusion in the Empire and allegiance to the crown was to be countered with the idea of ‘external association’, with Ireland associated by treaty with the British Empire while remaining independent. The North-East could maintain a regional parliament under Dáil Éireann.

In the course of the negotiations, Lloyd George succeeded in out-negotiating the Irish side. It is well stated by Seán Cronin: “The Irish delegation had two non-negotiable demands: national unity and independence. They lost both as point by point their case was whittled away through the diplomatic finesse of the British negotiators and their defences collapsed.” (‘Ireland since the Treaty’, Irish Freedom Press 1971).

How did it come about that the Irish were broken down in this way and ended up signing a Treaty that caused such division and strife? There are a number of reasons.

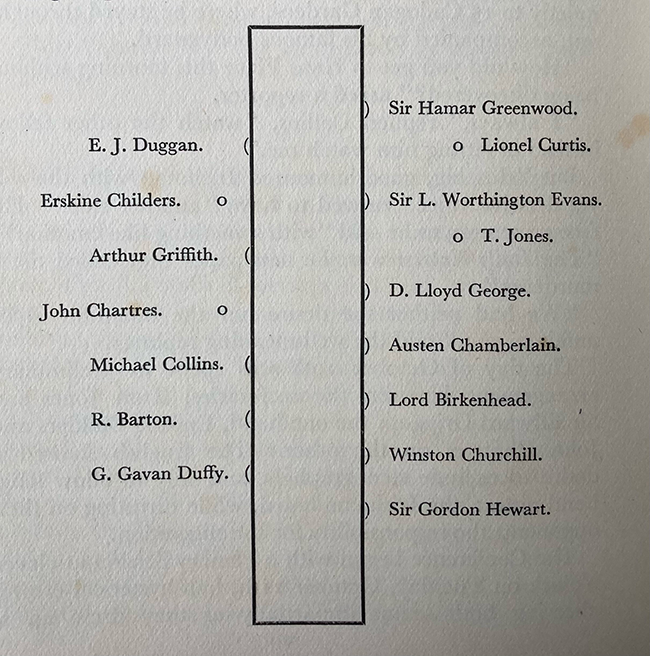

• The seating plan during negotiations

Existing divisions on the Irish side

There were both political and personal differences. The leader of the delegation Arthur Griffith was not a Republican and was prepared to go further in compromise than his colleagues. His inflated sense of personal honour was exploited by Lloyd George. At a key moment, he extracted from Griffith a commitment to accept the crown and Empire in return for ‘essential unity’ which was nothing more than the Boundary Commission.

Griffith had a fierce personal animosity towards Erskine Childers, the secretary of the Irish delegation, who had tried to ensure that they kept strictly to their instructions. Childers did not have a vote on the delegation, but his views were largely shared by delegates Robert Barton and George Gavan Duffy who did. This division was exploited by the British from early on.

The rift between Defence Minister Cathal Brugha and Finance Minister and IRA leader Michael Collins was already wide before the delegation was selected. In the Cabinet, Brugha and Austin Stack were the strongest opponents of any compromise that undermined the Republic.

The delegation was given an extremely difficult task of steering the talks towards De Valera’s concept of ‘external association’, a scheme not fully worked out. This was made even more difficult by the controversial absence from the negotiations of De Valera himself, an issue that had gone to a vote of the Cabinet with Dev using his casting vote.

• The Irish delegation returning from London after the Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921

Powers and instructions

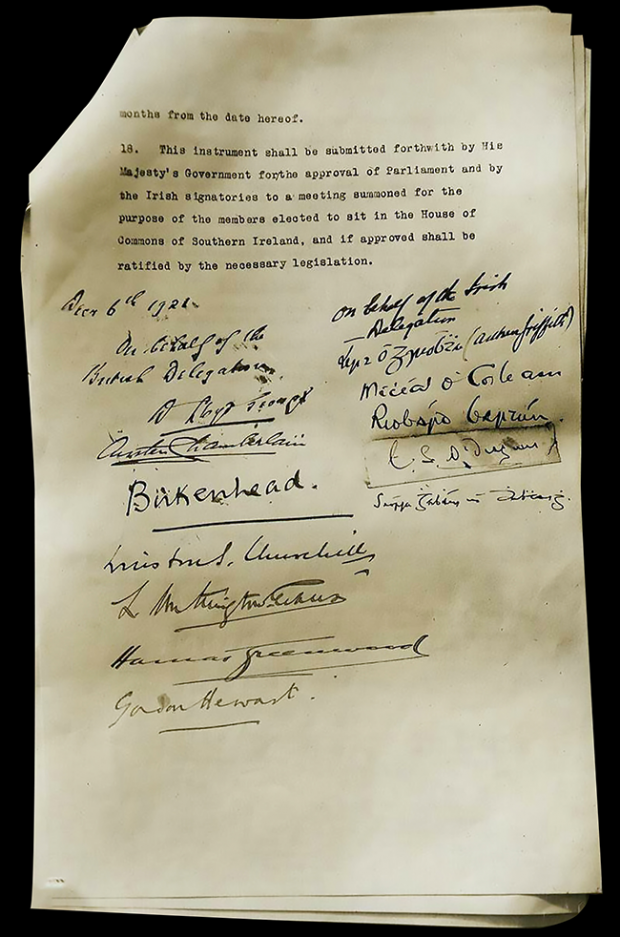

The delegates were ‘plenipotentiaries’ with full powers to negotiate and conclude a treaty or treaties. But their agreed instructions were to refer all major issues and any final treaty or treaties back to the Cabinet in Dublin before signing. When the crisis came, the delegation failed to refer the Treaty back before signing. To this day, the failure to do so seems incomprehensible and the only plausible explanation seems to be a combination of the divisions among the Irish negotiators and the threats made by Lloyd George and F.E. Smith.

The Boundary Commission

The Boundary Commission was crucial in persuading Collins in particular to accept the Treaty. Lloyd George had whittled down the delegation’s opposition to Partition. The Boundary Commission was first introduced by the British in the guise of a tactical manoeuvre to help pressurise the Unionist government of James Craig to agree to come under an all-Ireland parliament or else see their Six-County territory reduced.

Lloyd George dramatically threatened to resign if Craig did not agree. This impressed Griffith who, in return, gave his personal commitment to accept the crown and empire. But it was a bluff by Lloyd George that the Irish side failed to call. And then he sprung the trap, held Griffith to his commitment, and the only thing the Irish had to show for it was the Boundary Commission, now inserted as the main article in the Treaty relating to Partition.

Both Collins and Griffith seem to have believed genuinely that the Commission would result in Craig losing Counties Tyrone and Fermanagh and parts of Counties Armagh, Derry and Down, rendering ‘Northern Ireland’ unviable and leading to Irish unity. But this view of the Commission was never agreed by the Cabinet in Dublin and was one of the principal reasons why the Treaty should have been referred back.

British threats of war

The British threat to resume and escalate their war in Ireland hung over the negotiations from the beginning. Tory Minister F.E. Smith, on 19 August said that if negotiations broke down, the British would be “committed to hostilities on a scale never hitherto undertaken by this country against Ireland”.

De Valera said repeatedly that the Irish people must be prepared for the possibility of a resumption of war if the negotiations broke down. But it was at the negotiations in those final hours on 5 and 6 December 1921 that Lloyd George deployed the threat of war most effectively. He said that each of the Irish delegates, if they refused to sign, would be personally responsible for war and it would be immediate and terrible.

Perhaps the greatest single failing of the delegation was that they succumbed to this threat. They allowed it to prevent them referring the final draft back to Dublin as Lloyd George pressed them to sign or face disaster. The British certainly had the resources to resume war but whether it was politically possible for them to do so after negotiating for months was highly doubtful, a fact which the Irish delegation seemed to have considered little if at all.

The Treaty was signed and the delegates returned to Dublin where the Cabinet, Dáil Éireann, and the IRA were soon deeply divided. But there was nothing inevitable about the Civil War that broke out in June 1922. For that, other forces within Ireland and the intervention of the British government again were crucial.

The Treaty had the backing of the wealthy and privileged in the 26 Counties, including the Catholic hierarchy. Big business interests backed it, as reflected in the editorial stand of all but a handful of newspapers, both national and local. These forces pushed powerfully on the Free State leaders.

And the British government was determined that their recasting of the conquest would not fail. They stopped Collins from producing a Free State constitution that would be an advance from the Treaty. They thwarted his efforts to assist nationalists in the Six Counties. They deplored peace efforts with the anti-Treaty IRA. They drew Collins and Griffith ever closer and pressed them relentlessly, until they succumbed, to attack the anti-Treaty IRA in the Four Courts.

The recasting of the conquest was seen most sharply in the Six Counties where nationalists were now trapped in the new Orange state. There would be more pogroms, mass imprisonment, gerrymandering, and corruption, beginning 50 years of one-party Unionist rule. The Boundary Commission was to prove a fraud, eventually yielding absolutely nothing and entrenching the Orange state behind an unaltered and hardened border in 1925. And it is this last and most poisonous and persistent legacy of the Treaty that remains to be abolished today.

The Treaty – some key quotes

“I … do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I do not and shall not yield a voluntary support to any pretended Government, authority or power within Ireland hostile and inimical thereto, and I further swear (or affirm) that to the best of my knowledge and ability I will support and defend the Irish Republic and the Government of the Irish Republic, which is Dáil Éireann, against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and I will bear true allegiance to the same, and that I take this obligation freely and without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion, so help me God.” – Oath taken by all TDs and IRA Volunteers 1919-1921.

“I … do solemnly swear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State as by law established and that I will be faithful to H.M. King George V, his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of the group of nations forming the British commonwealth of Nations.” – Oath in the Treaty signed 6 December 1921.

“Sinn Féin demanded an independent, sovereign Republic for the whole of Ireland, including Ulster. We insisted upon allegiance to the Crown, partnership in the Empire, facilities and securities for the Navy, and complete option for Ulster. Every one of these conditions is embodied in the Treaty.” – Winston Churchill.

“My idea is the Workers’ Republic for which Connolly died. And I say that that is one of the things that England wishes to prevent. She would sooner give us Home Rule than a democratic Republic. It is the capitalists’ interests in England and Ireland that are pushing this Treaty to block the march of the working people in England and Ireland.” – Constance Markievicz, Dáil speech against the Treaty.