5 December 2021

Centenary of a catastrophe - the signing of the Treaty

Remembering the Past - 100 years ago

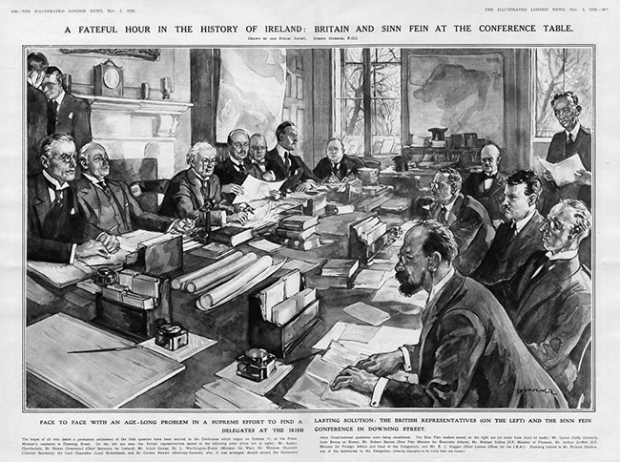

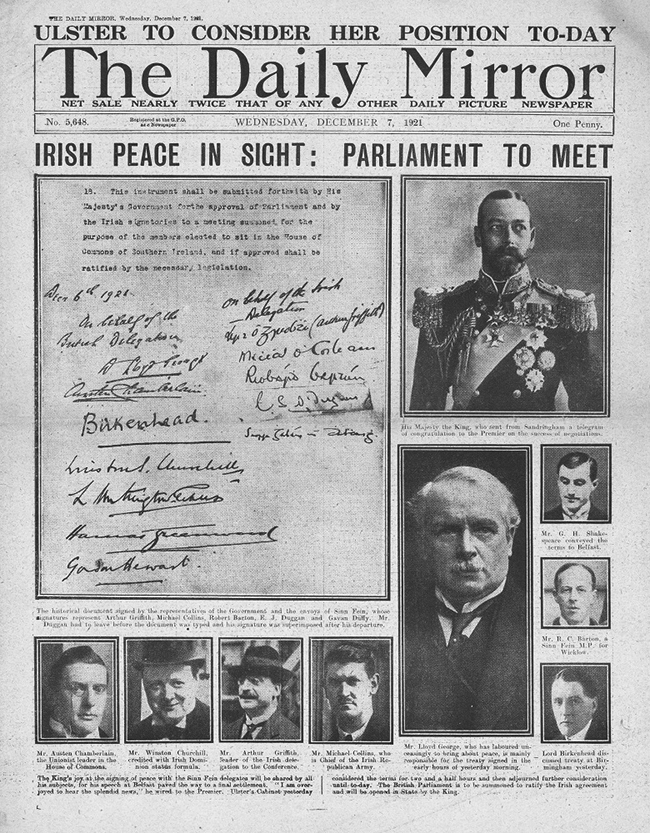

The ‘Articles of Agreement’ commonly known as the Treaty were signed in London in the early hours of the morning of 6 December 1921. They were signed by a divided Irish delegation under threat of an immediate resumption and escalation of the British government’s war of terror in Ireland.

Three days earlier on 3 December in Dublin the Irish negotiators attended a tense Dáil Cabinet meeting. They had with them the latest British draft. During heated debate Cathal Brugha said that the document, if signed, it would split Ireland from top to bottom. The Cabinet did not approve it but sent the delegation back to negotiate further. They had their instructions that any final treaty or treaties must be referred back and approved by the Cabinet before signing.

British Prime Minister Lloyd George had prepared the ground well for the culmination of the many weeks of negotiations in London. He had secured from Arthur Griffith a personal commitment not to break on the issue of the Ireland’s inclusion in the British Empire. In return Lloyd George claimed that he would put pressure on Unionist leader and ‘Northern Ireland’ Prime Minister James Craig to come in under an all-Ireland parliament. Lloyd George presented himself as staking his political future on this, pointing to the Tory Unionists in his Cabinet and the Tory grassroots that they had to satisfy. There was a double threat of war – from Lloyd George himself if the talks broke down and from the prospect of his replacement with a Tory government that would be more likely to resume the war.

When the Irish delegation arrived back in London Robert Barton, George Gavan Duffy and Erskine Childers began drafting counter-proposals based on the Irish Cabinet position. The divisions in the delegation were deep by this stage and Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins and Eamonn Duggan refused to go to Downing Street with the counter-proposals. When Barton and Duffy said they would go alone, Griffith agreed to join them.

The Irish counter-proposals of 4 December reflected the concessions made on the Irish side during the weeks of talks, they even included an oath recognising “the King of Great Britain as Head of the Associated States” of the British Commonwealth. But the British rejected the counter-proposals out of hand and when Gavan Duffy said that the difficulty was coming into the Empire the British delegates got up and walked out, seeming to signal that the talks were over. But they were not over, Lloyd George’s had more moves to play.

Lloyd George asked to see Collins alone in Downing Street on the morning of 5 December and Collins agreed. At that meeting Lloyd George held out the Boundary Commission as the solution to Partition and Collins in his note to his colleagues afterwards said that with the Commission “we would save Tyrone, Fermanagh and parts of Derry, Armagh and Down”.

Later that day the Irish delegation returned to Downing Street. The British produced a memorandum which stated that if ‘Ulster’ (meaning in this case the Six Counties of ‘Northern Ireland’) did not agree to come in under an all-Ireland parliament, the British would proceed to create such a parliament but allow ‘Northern Ireland’ to opt out of it, in which case there would be a Boundary Commission. Griffith then made a crucial and, for the Irish cause, a politically fatal intervention. He said that he personally would sign the Treaty. Historian Dorothy Macardle wrote:

“That indeed, was the moment of Lloyd George’s triumph. Arthur Griffith’s lifelong loyalty to Ireland, his loyalty to his Government, to his colleagues, to his mission and to his Republican oath, had given way before loyalty to a promise, made as part of a tactical maneuver, to Lloyd George. It could hardly have happened if Griffith had not in his own mind been satisfied with the prospect of an Ireland within the Empire, under the crown.” (‘The Irish Republic’ by Dorothy Macardle).

With Griffith in the bag, Lloyd George then went after the other delegates and used the full threat of war. He produced two envelopes which he claimed contained letters to Craig – one saying a deal had been reached and the other that talks had broken down and there would be war. In Austen Chamberlain’s recollection Lloyd George said it would be “war - and war in three days!”

The final British draft reached the Irish delegation at 9pm at Hans Place and decisions had to be made. While Griffith was the leader of the delegation, Collins was seen as the ‘strong man’ and his leadership role in the IRA and the IRB was crucial. Convinced that the Boundary Commission would make ‘Northern Ireland’ unworkable, and with the secret backing of the IRB for his position, Collins was prepared to sign, later justifying himself by saying that the Treaty gave “the freedom to achieve freedom”.

Griffith worked on Barton and Duffy, giving Lloyd George’s threat of war full credibility. Though opposed to signing, Barton believed the threat and later recalled that the British Prime Minister had declared “with solemnity and power of conviction” that “the signature and recommendation of every member of our delegation was necessary or war would follow immediately”. He agreed to sign. Duffy did not believe the threat of war was real but with Griffith, Duggan, Collins and Barton now prepared to sign he was not prepared to take sole responsibility and agreed to sign under duress.

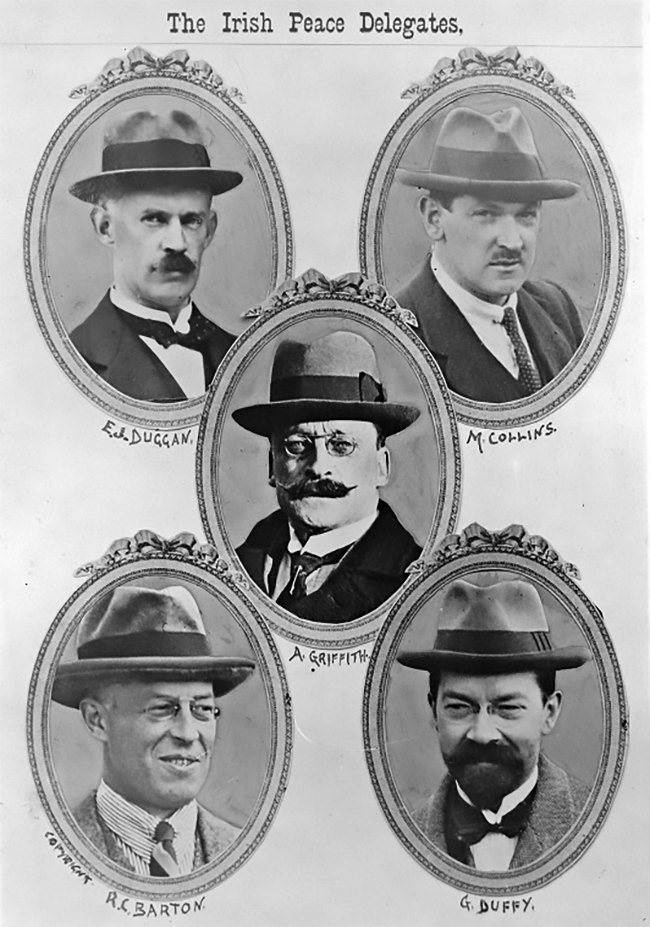

• The Irish negotiations team: Arthur Griffith, Eamonn Duggan, Erskine Childers, Michael Collins, George Gavan Duffy, Robert Barton and John Chartres

The divided Irish delegation acted under the British threat of war and no-one seems to have seriously questioned if that threat was a bluff. While the British certainly had the capacity to resume war (how ‘immediate’ was open to question), could they have done so politically, given that they had been negotiating for months? The eyes of the world, especially the United States, were on the Irish talks in London. Yet the Irish delegation does not seem to have considered using that advantage to the full by exposing the British threat to public view and refusing to proceed unless the threat was withdrawn.

Much has been written about the capacity of the IRA to resume armed resistance. Assessments of this were coloured by the Treaty division itself and the Civil War, with both sides making different claims. But having successfully resisted overwhelming British force since 1919 how could it be credibly argued that, with a united military and political leadership, in the face of British aggression, and after genuine Irish efforts to negotiate peace, resistance could not have been sustained? Remember, the task of a guerilla army was not to defeat the conventional enemy forces in the field but to sustain itself and its support among the people, keeping up resistance until further political progress could be achieved.

Succumbing to the threat of war, the delegation did not refer the Articles of Agreement back to the Cabinet in Dublin as their instructions obliged them to do. They did not even telephone to Ireland to report back. They returned to 10 Downing Street on the night of 5 December and the Treaty was signed there at 2.15am on Tuesday 6 December 1921.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures