19 August 2021 Edition

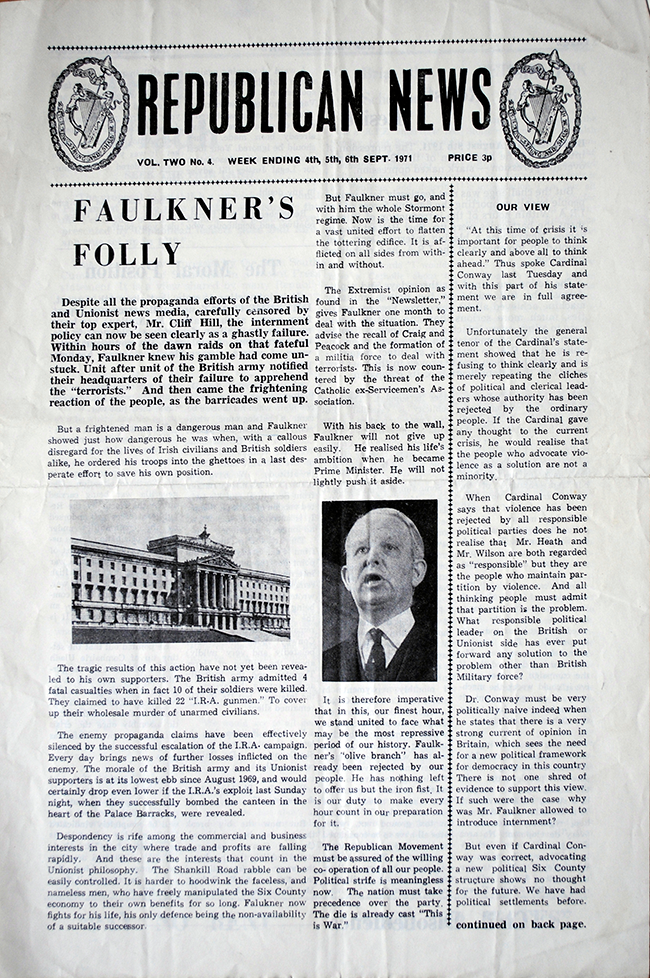

Internment 1971 – Operation Demetrius remembered

Imprisoning citizens without trial has been a feature of political life in Ireland for the long century since 1916. North and South of the border it was a tool used by the unionist and Dublin governments, to constrain and deflect republican struggle.

However, despite the folk memory of internment, it is hard to conceptualise today the scale, or the shock of the imposition of internment without trial in the Six Counties in 1971. It is a challenge to fully comprehend the extent of the attack on already repressed nationalist communities across the Six Counties, who were being increasingly encircled and ghettoised since the pogroms of 1969.

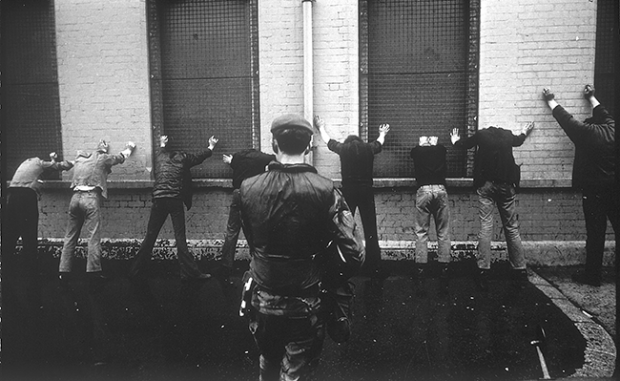

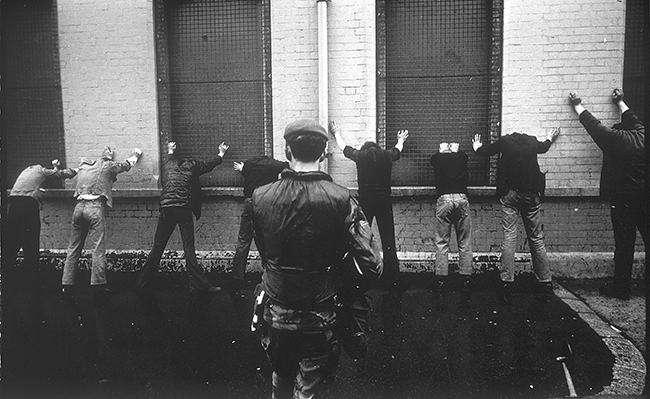

On 9 August 1971, the British Army, under the cover of darkness, swamped nationalist communities, detaining 342 people in what they had named Operation Demetrius. In West Belfast, over 2,000 troops were deployed to make arrests. At the end of that day, 12 people had been killed in the North. By the time internment was ended in 1975, nearly 2,000 people had been detained.

To mark the 50th anniversary of internment, An Phoblacht has excerpts from the never before published diaries of Jimmy Drumm. Mícheál Mac Donncha sample’s Jimmy’s first-hand accounts of August 1971. Danny Morrison also gave us access to his compelling diary from 1971, while Peadar Whelan looks at the longer-term implications of internment in the decades that followed. We also reprint a 2007 interview by Ella O’Dwyer with Margaret Shannon.

'Barbed wire abounding'

Jimmy Drumm’s Internment diary

One of the hundreds of men and boys arrested by the British Army during the Internment swoop on the morning of 9 August 1971 was veteran Belfast Republican Jimmy Drumm. He was brought to Crumlin Road where he had been imprisoned as a teenager 33 years previously. Having served that first sentence in 1938, he was immediately interned and remained in the ‘Crum’ and Derry Jail until the end of World War Two.

After his first release in 1945, Jimmy married Máire McAteer, a Republican from South Armagh. They had five children to whom they were devoted, but Jimmy was taken from them and interned again from 1956 to 1960. So, he was well into middle age when the British crown forces descended once more on the family home that August 50 years ago, arresting Jimmy and his son Seán. Máire was in Armagh Prison, serving a six-month sentence for encouraging people to join the IRA at a meeting in Turf Lodge a month before Internment.

Máire Drumm herself highlighted the years Jimmy had spent under British lock and key. Speaking in 1972, she said:

“At the present time, I’m a married woman with a husband in Long Kesh who has been interned for 13 years altogether in three different phases of internment without trial. He went back in 1956 and was in until 1960. Now he’s back since August 9 1971. I’ve had three periods of internment in my life in that I’ve suffered internment as a young girl, having a fiancé in prison, then as a young wife with a husband in prison and five children to rear on my own. And now as a middle-aged woman, my husband who’s also middle aged is back in prison again.”

Jimmy kept a diary vividly describing his arrest, interrogation, weeks in the ‘Crum’ and then the move to the newly opened Long Kesh Internment Camp. The diary is written in tiny, but fluent, and legible handwriting and records his own experiences and that of his family, the life of the prisoners and the news they were receiving from outside as the conflict escalated.

It runs from 9 August 1971 to 6 June 1972 when Jimmy was released. He and Máire continued their tireless work in the Republican Movement. Máire became Vice-President of Sinn Féin and was assassinated in her hospital bed by pro-British forces in 1976. Jimmy survived her by 25 years and died in 2001 after a long illness.

Jimmy Drumm’s Internment Diary is a unique document and an important source for the history of the republican struggle in that era. The diary is in the possession of Jimmy and Máire’s son Séamus Ó Droma who has made it available now for publication for the first time. We carry here extracts from the diary covering the Internment arrest, Girdwood British Army barracks, Crumlin Road Prison and the first days in Long Kesh.

Monday 9th August 1971

Soldiers of the British Army came to my home at 5am. Heard the screech of brakes, looked out and saw soldiers with blackened faces scrambling from an armoured vehicle (a ‘Pig’). Beckoned to us to come down – opened the door and they burst in. “Hurry, you’re coming with us.” Insisted on getting dressed. Ordered Máire and Seán downstairs. Kept insisting I “hurry!” whilst dressing - took my time.

Máire came running upstairs “Daddy, they’re taking Seán!” I couldn’t believe it. “They are, have ordered him out in his pyjamas.” Máire grabbed a pullover for him – I handed him my anorak.

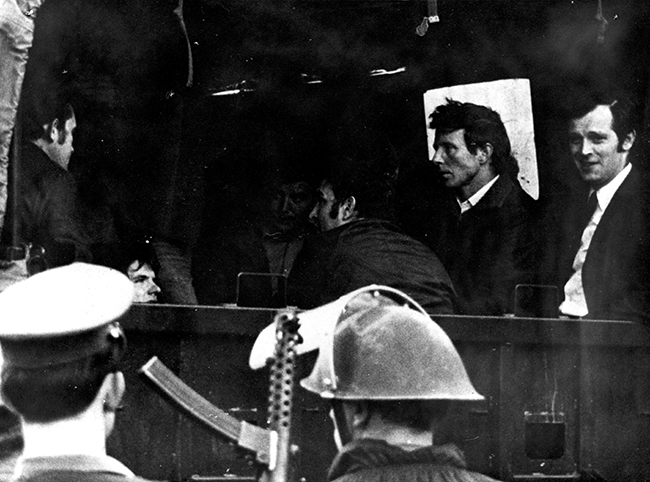

Bundled into ‘Pig’ and driven around to checkpoint at corner of Shaw’s Rd – Stewartstown Rd. Whole convoy of army vehicles assembled. Officer took over. Took our names, ordered that we be stripped of all possessions inc. ties, bootlaces, hands tied behind backs and put into army personnel carrier (canvas covered). Seán Boyle and Grey there already. 4 soldiers in with us, issuing verbal threats and obscenities what they’d do to us! Up Kennedy Way and and Monagh Rd.

In Turf Lodge ambushed by friends! Shower of bricks and bottles rained in on us – threw ourselves to the ground. Soldiers panicked – threw a gas canister which girl smothered with bin lid. Further ambushes going through Ballymurphy. Soldiers went wild – “Paddy b[astard]s, lousy Irish b[astard]s, another stone and we will shoot you.”

Down Shankill Rd, soldiers singing ‘The Sash’ etc. “Start praying to your B. Virgin now. We’ll throw you out to the Protestants” etc etc. Eventually made our way by side streets to Girdwood Park Army Barracks. Kept waiting half hour or longer whilst soldiers excelled themselves with threats of what they’d do to us. Alsatians barking and helicopter propellers churning away. (We were sure we’d be transported to England). Saw men being pushed and prodded along.

Eventually pushed out of lorry and roughly grabbed and shoved into ‘Reception’ (foyer of barrack gymnasium). Saw lot of old familiar faces straight away Larry and Joe McGurk, Gerry Maguire, Brendan etc. Name, address noted, instamatic cameras clicking away taking our photographs. Heard “Drumm” being called. Into gymnasium where 100 or more were seated on floor without back support. Wondered where Seán was. Hadn’t long to wait. 3 men, Seán Murphy, Seán and another came in. Pushed into room, gasping, Seán holding his side, obviously got beating. (Learned afterwards they had to run gauntlet of military policemen, and kicked and batoned the whole time. Our shoes had been removed. Seán had no stockings so suffered more.)

At intervals groups of 5 or 6 men were removed and received the ‘treatment’. Then interrogation by Special Branch and CID commenced. I was called out by MPs but mercifully at the same time detectives came looking me for interrogation. More form filling in. Name, occupation, dependents, etc. When did I join the IRA etc. Refused to answer. “This will probably mean internment.”

Back to another room upper floor. MPs pacing up and down, barking threats. “Open your mouth.” Then batches of 6 called out (amongst them Seán), learned afterwards they had to run gauntlet again in bare feet over broken glass to prison. Eventually about 80 left. Taken back to gymnasium in same position (around 1pm). Some time later got small amount of tea. Kept sitting floor until around 9pm when it was announced: “You’re to be our guests for the night.” Were issued with beds, eventually lay down to rest! Every ½ hour CID came around beds pulling back bedclothes looking for particular men to interrogate.

Tuesday 10th August

Then at 2am, “Rise and shine” and ordered out of bed for name-taking exercise. Wakened again at 7am (?), back to sitting on floor. Out to exercise on football pitch for ½ hour walking around – no talking! Plate of watery stew for dinner about 9pm. Harry Taylor and officials entered room. 12 names called out, took property and left, followed by another 11. H. Taylor (about midnight) came and told me Seán had been released from Crumlin Jail with a batch of other prisoners in the midst of gunfire but they were alright.

All day rumours whispered around that 24 people (including a priest) had died on Monday night in gun battles. Later learned that 15 people had in fact died. Kept sitting around until 3am when we were called out in batches of 6 – shown detention order, photographed. Line of RUC men on either side of us preceded by armed MP, another bringing up rear. Order given “Move! At the double!” Prodded by RUC across Girdwood, through hole in wall, into prison garden thence to ‘B’ Wing and Reception. After Reception moved to Cell 15 C3 in company of Liam Sheppard.

Thursday 12th August

Meetings today between different groups to settle question of O/C and staff. I acted as “go between”. Eventually J. O’Rawe O/C, Billy O’Neill on Staff with him, Art McMillen Adj and Michael Farrell. Myself in charge of parcels and letters. Got parcel from home. Laundry, sweets, shaving gear etc.

Friday 13th August

Today I should have been commencing my holiday…Saw press conference on TV Joe Cahill, P. Kennedy, and John Kelly. Joe stated that IRA had 30 members detained and 2 dead and 8 wounded.

Friday 20th August

Surprise visit this am from Máire, accompanied by Miss Totten, wardress. Lasted three quarters of an hour. Miss Kennedy came in and we were able to straighten out most of our problems. [Máire] was looking well. Papers full of protests and stories of brutality now fully reported in press. A beautiful day today. Sunning ourselves all day. Peter Bunting freed this afternoon. Smyth (Dublin) taken to Prison Hospital. Heard explosions.

Thursday 2nd September

Parade today in memory of T. Williams. Joe Cahill detained on arrival at Kennedy Airport, declared intent was money for arms. Immigration application for return to Ireland adjourned for week. Lynch to visit Heath next week. Midday explosions in centre of city caused panic...

Sunday 19th September

Rumours going around after Mass this am of a shift to Long Kesh were confirmed! 88 of us were going by helicopter in batches of 6. At 2pm I was in the fourth batch in company of B. McGrath, P. Smith, D. Hannaway, Jim May, C. Notarantonio. We were escorted to playing field of prison by warders and escorted to waiting helicopter. Escort of 6 warders accompanied us in our short 10 min journey over Belfast. All landmarks easily visible. I even got a glimpse of our house!

On arrival at Long Kesh we were herded into an army tent and left in groups for doctor, photographing etc and finally to Hut 16. Bunk beds (20) – 40 in our hut. Next hut 20 and rear of this hut used as dining room. Were surprised (disagreeably) to find that we were in a compound of 60 men. 2 huts and a further one containing toilets, wash hand basins and showers. Completely wired off from other compounds. Nearest compound to us consisting of 3 huts – the Maidstone men and remainder of our 88. Hut is a new corrugated iron Nissen type, electric heater and locker per man. We got a dinner at tea time, quite satisfactory. Personal property sent on by lorry delivered to us tonight. We were able to carry on sing song across the wires to Maidstone compound and shouted greetings. Recognised J. McMahon, J. Davey, J. McKenna, J. Savage, P. O’Hagan. Camp surrounded by 10ft corrugated paling. Army sentry box at each corner mounted on stilts. Barbed wire abounding.

Monday 20th September

The morning after the night before and Long Kesh doesn’t look any better! I awake at 6am (didn’t go to sleep until 1am). At 6am Johnny Collins roused the occupants of Hut 6 with a spirited rendition of ‘The Old Bog Road’ on the accordion. Door open at 7.30am, out for wash, and many had showers. Breakfast at 8.45am – weetabix, sausage, bacon and beans, tea, bread, marg. No papers or letters. Visits commenced at 12 noon. Jim O’Kane had visit, reported that wife had to practically undress to satisfy women police searches. (Later denied by Governor). Further visits followed – K. O’Rawe etc but they stated that only their handbags and shoes were searched. P.O. told me that Máire had phoned enquiring if visit tomorrow stood – was told it did. Also informed from Miss Kennedy (Welfare, Crumlin Rd) “that property stolen during raid on our house was not at Hastings St Barracks, - letter following”.

Asked to conduct election of O/C Compund. John O’Rawe - 45 votes D. O’Hagan – 0. J. O’Rawe now O/C. Staff O/C J. O’Rawe, Billy O’Neill, J. Maguire, O. Kelly, P. Hartley, D. O’Hagan. Later interview with rep of Ministry of Home Affairs elicited little. Points raised – confinement, recreation etc. F. McGarry O/C of large compound. B. McKenna also took part in talks. Are entitled to 4 letters per week – got one tonight. Will write to Máire after visit tomorrow. Wonder how girls will travel. No public transport. Prison mini-bus picks up visitors at car park. Parcels left in today not given out – obviously understaffed. Shudder to think what delay will be with outgoing and incoming letters. Scene as I write – 11pm. Some watching tv, playing cards, reading, writing and decorating hankies. Dinner – soup, pie, potatoes, cabbage, sweet (sponge and custard). Tea – sausage rolls, potatoes, bread, tea, marg. V. poor, below Crumlin Rd. standard.

'A huge wartime feeling and a sense that we’re all in this together'

Excerpts from Danny Morrison’s August 1971 diary

Danny Morrison was 18 and a student when internment was introduced. He lived in the Broadway/Iveagh/Beechmount area of the Falls in Belfast. The following account is based on a diary he kept during that time

August 9, Monday

Listened to the radio. The first news of the day said that a soldier’s been shot dead and there’s rioting in all nationalist parts of Belfast, in Derry, Newry and Omagh.

Outside our house there was shouting and screaming. There’s been raids and arrests and talk that ‘they’ve introduced internment’.

We began putting up barricades, which we’d last done in August 1969. Two on Broadway and one across Beechmount Avenue. Side streets on the Falls being kept clear for access for fighting. Milk bottles collected for petrol bombs.

We rioted at the top of Iveagh Parade, the neighbours in other streets out in huge numbers. When armoured cars or military jeeps flew past we let them have everything we’d got — bricks, rocks, stones, hammers, wrenches, petrol bombs — then swarmed onto the main road to retrieve weapons and show the retreating soldiers the numbers against them, that we despise them.

Mostly young but older ones also threw and those who couldn’t riot made us sandwiches and sent drinks up to the street corner. Incredible sense of morale.

Heard another two people have been killed. Heard shooting throughout the day, coming from the Murph or Whiterock. Radio Free Belfast’s back on air. Broadcasting messages of resistance, playing republican songs and telling people to be wary of rumours.

Rioted as long as the soldiers came, never feeling exhausted. Swede said we should get on top of the Co-Op roof and drop paint and bottles of petrol onto the armoured cars speeding past, then further along people could set them alight with petrol bombs to immobilise them.

Saw that bastard Brian Faulkner on TV announcing they’d introduced internment. Hateful. Only ones arrested have been Catholics.

Coming across Beechmount after midnight shots were fired close to us but we could see no Brits out on foot. Later learnt that the Brits shot and wounded Marty Devine at the corner of Beechmount Drive. There was more heavy shooting around Broadway and the Donegal Road.

Heard that ten people were now dead. Go to bed for a few hours.

August 10, Tuesday

News says now fourteen dead, many wounded, rioting in many towns.

The Brits tried to take down our barricades and we resisted.

Two soldiers in Andersonstown and another two in the Lower Falls wounded by snipers.

Rioting broke out from Broadway to Beechmount. We were out in even greater numbers, then the Brits opened fire and several struck the wall in Islandbawn Street. Later, they got out of a Saracen at the Avenue and took up positions in Daly’s Garage.

We replied with stones and bottles. Was standing at the top of Iveagh Drive when a soldier fired at me. Bullet went through the window of the Squirrel sweetie shop. He fired again and this time the bullet struck the ground a few feet in front of me and ricocheted, striking the gable wall in the entry behind me. Eventually we were pinned down with the Brits at Beechmount Avenue firing shots every now and then to keep the road clear. Heard that Eddie Doherty from Iveagh Street was shot dead by Brits on the Whiterock. He’s married with kids.

Met a nurse from the country. She was doing first aid on people who were injured, including my cousin Thomas McKee. Her name’s Carmel. She’s about two or three years older than me. I’ve no chance. She’s in digs on the front of the road.

Around about 11pm there was a rumour of trouble at the Broadway barricade. Lads were sent down. Me and Tony Taylor remained at the top of the Parade, next to the big ‘Guinness is Good For You’ billboard. Suddenly shots rang out and we dived to the ground. The shots went through the advertisement. My elbows were bleeding. Swede’s brother-in-law Gerry Deery gave me plasters and we went out again. The heavy shooting continued but it was all the Brits. Had a huge row with a local IRA man. Lads were screaming at him and giving him abuse. Why weren’t the IRA firing back? Where were they? If you don’t want to use your guns given them to us. He took as much as he could, then turned and walked away.

[It was only later that I learnt that the IRA had ordered no action in Beechmount. It wanted the area quiet so that they could meet in safe houses there and organise operations.]

August 11, Wednesday

I got a few hours sleep but was woke at twenty past four by the sound of bin lids. I jumped out of bed and went out but the raids must have been in Rodney and St James. The noise of banging bin lids was continuous. The brickyard at the top of Beechmount was set alight. There was more rioting and the number killed so far is twenty-two or more. There are no deliveries and the women have walked down to the loyalist Village area to buy food in the shops there.

We were joined by a group of Dubs who came up give us a hand. Things became quiet but were quite tense. Went home at half two.

August 12, Thursday

McCavanagh’s next door was hit in the early hours. Brits took away Danny McCavanagh, Jim Duff, Noel Maguire and one of the Dublin lads, Frank Power, who was staying there. Women came out banging bin lids. When I went to go out my mammy cried and begged me not to go. She didn’t want to see me killed. I was conflicted and spent some time in the house until she calmed down, then I went out.

There’s a huge wartime feeling and a sense that we’re all in this together. Peter Fox and I hoisted the Tricolour from the top of the Co-Op roof.

Aunty Eileen in England phoned up, wanting the family to move to Bury. Daddy would love to go but mammy would never leave her sisters and brothers or Belfast. Granny Morrison packed up Springview Street and Uncle Gerard, Harriet and kids have cleared out Crocus Street and are on their way to England. Said they’ll not be back.

After we finished rioting tonight a Norwegian photographer from Oslo asked if he could take our pictures. He asked us, ‘Do you consider yourselves revolutionaries?’ Tear it down! Form our own democracy! Yes!

August 13, Friday

During the night hundreds of soldiers removed all our barricades and opened up all streets. It had been pouring down. Not good weather for fighting. Frank Power’s brother Seán arrived from Dublin, worried sick, looking for him. I took him up to Rockmount Road to someone who said they’d seen him in Girdwood Barracks and he was beaten up. We came back down the road and met my mammy who told us Frank had been released. But we couldn’t find him. I got Seán a lift to Clonard Monastery where they’ll give him a room for the night.

Heard shooting from Beechmount tonight. This time is was the IRA.

August 14, Saturday

Heard that Frank Power had hitchhiked into the city centre and got the train to Dublin. During all the rioting I never got saying goodbye to our Geraldine who’s gone to live in England and get married. Peter and I walked into town. In Harrison’s record shop I bought 'Avalon' by Mathew Ellis and in Eason’s 'The Irish Republic' by Dorothy Macardle.

Operation Demetrius: Internment and the infamy of Long Kesh

By Peadar Whelan

As street warfare erupted across the Six Counties, the next chapter of the internment story was being written as detainees were systematically beaten in interrogation centres

On Sunday 8 August, hundreds of people marched through the streets of Ballymurphy in West Belfast to mark the 50th anniversary of the Ballymurphy Massacre, carried out by British paratroopers deployed to suppress the rage of a nationalist community incensed at the introduction of internment and the violence of the unionist state directed against them.

The march was all the more poignant as the echoes of the recent judicial verdict, confirming that the dead were unjustifiably killed by the British Army, reverberated through the march.

Among the marchers were campaigners from Derry’s Bloody Sunday group whose campaign for justice inspired the Ballymurphy families. There were also families from the Springhill/Westrock Massacre Campaign, highlighting their demand for justice for five unarmed civilians shot dead in July 1972 by Paratroopers.

Throughout the demonstration, the seething anger of the marchers could be felt, incensed at the British government’s plans to introduce amnesty legislation, their latest plan to prevent investigations and inquiries into the political/military strategies employed by the British state over the years of the Northern conflict.

The numerous banners from Derry, to the McGurk’s and Kelly’s bar bombings, to the Loughinisland Massacre and the families from Mid-Ulster – Tyrone and Derry – carried at the demonstration represented not only a geographical spread of Britain’s war, but also pointed to the various levels of British state activity in the conflict, including the use of unionist death squads.

That Sunday’s March for Truth took place on the eve of the 50th anniversary of Operation Demetrius, the military invasion of nationalist areas in August 1971, which saw 342 people from republican, socialist, and civil rights backgrounds rounded up and interned, ensuring that one of the seminal moments of our recent history was in focus.

Internment, used successfully against the IRA in the 1920s, 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s was the go-to form of suppression. However, the newly elected leader of the unionist party Brian Faulkner went further by sanctioning the killing of nationalists with his ‘shoot with effect’ order. This shows that the Ulster Unionist Party, riven by infighting, chose ever more repression, rather than real democratic change.

The events of July 1971 in Derry when civilians Seamus Cusack and Dessie Beattie were shot dead by British soldiers showed that the British Army were up for the task of ‘shooting with effect’!

That unionism wasn’t interested in a political solution at this stage is clear from the comments of John Taylor, Minister for Home Affairs, who defended the “action taken by the army … against subversives … when it was necessary to actually shoot to kill”.

Taylor warned, “I feel it may be necessary to shoot even more in the forthcoming months”. This was on 18 July. The next day, Faulkner called British Prime Minister Edward Heath to cajole him into introducing internment.

On 5 August after a meeting between Faulkner and the British government, internment was agreed for 9 August and, in a prelude to what lay in store for the nationalist community, a paratrooper shot South Armagh man Harry Thornton dead on 7 August as he drove along West Belfast’s Springfield Road.

As the armoured cars and raiding parties swooped into nationalist areas, smashing their way into homes to arrest ‘suspects’, the palpable anger of those communities brought people onto the streets.

And John Taylor’s warning was fulfilled. Before the month was out, the British Army killed 23 people, the youngest being 14-year-old Desmond Healy, shot dead in Lenadoon.

As street warfare erupted across the Six Counties, the next chapter of the internment story was being written as detainees were systematically beaten in interrogation centres.

For 14 of them, the nightmare of ‘deep interrogation’ began as they were spirited off to a secret location, later identified as the British military base in Ballykelly, County Derry, where they were subjected to interrogation under a methodology known as the Five Techniques.

Journalist Ian Cobain’s 2014 book ‘Cruel Britannia’, confirmed that the Five Techniques were authorised at the highest level of the British government and “ill treatment of selected prisoners had been an integral part of British military doctrine for years”.

While initially classified as “torture” by the European Court of Human Rights in a case taken against the British by the Dublin government, the ECHR, after the British appealed, downgraded the ruling finding the British guilty of using only “inhuman and degrading treatment”. This ruling opened the door for the rendition of suspects in the United States and Britain’s so-called ‘war on terror’ and was relied upon by Israeli torturers in their interrogation of Palestinian prisoners.

Those interned on or just after 9 August were held in Armagh women’s prison, Crumlin Road jail, and on the Maidstone, a British Royal Navy vessel anchored in Belfast Lough before their transfer to the Long Kesh site outside Lisburn.

Sentenced prisoners were also incarcerated in The Kesh where they were moved to after the British succumbed to a Hunger Strike by IRA prisoners and granted them ‘Special Category Status’.

The notoriety of the prison soon made it a watchword for abuse. When, in October 1974, the IRA prisoners fed up with their ill-treatment by British soldiers and loyalist prison warders torched the prison, it was clear that the war on republican prisoners had reached a new level.

The deployment of SAS special forces units and the use of the CR Gas, classed as a chemical weapon, is one of the hidden stories of the conflict and the history of the prison camp.

Volunteers Francis Dodds, Teddy Campbell, Patrick Teer, Hugh Coney, Jim Moyne, Henry Heaney, Sean Bateson, and Pól Kinsella all died in Long Kesh. While their death certificates might put the deaths of the others down to natural causes, there was deliberate medical neglect in most cases that contributed to their deaths.

Volunteer Hugh Coney was shot dead by a British soldier in 1974 as he tried to escape from the camp in the aftermath of ‘The Burning’.

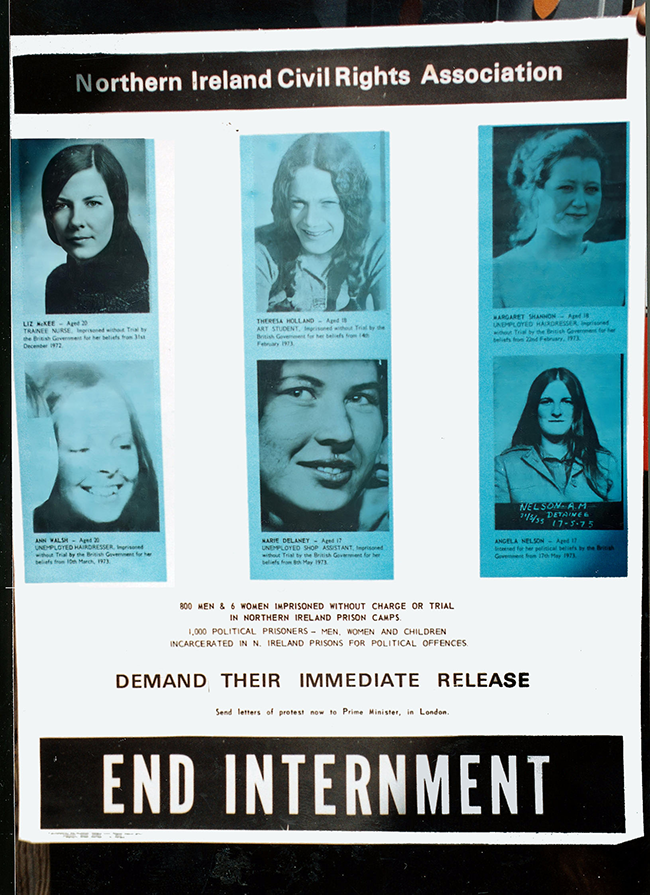

Liz McKee was the first republican woman to be interned, arrested on New Year’s Day 1973. She would be ultimately joined by 30 other women who were held in Armagh jail. Among those incarcerated with her was her close friend Tish Holland who was just 17 when arrested.

Only 107 loyalists were interned. The first only in February 1973, despite the fact that the UVF and UDA were responsible for some of the most notorious incidents of the conflict, including the McGurk’s Bar bombing in 1971 and the Dublin/Monaghan bombings in 1974. It was an indication of the laissez-faire attitude the British had to loyalist violence.

When internment was phased out in 1974, the last internees were released in December. It was a time of hope as the IRA had met Protestant clergy in Feakle, County Clare and a ceasefire was implemented.

Sinn Féin would be legalised as a sign of ‘British goodwill’. However as with Troy, the British wooden Horse was full of dirty tricks and the dark days of H Blocks, Blanket and No Wash Protest, and the killing of Ten Hunger Strikers by the Thatcher regime lay ahead of us.

Never again

Margaret Shannon on her internment experience, talking to Ella O'Dwyer

This article was first published in An Phoblacht, July 2007

Internment detainees were overwhelmingly male but among the women interned was Belfast woman Margaret Shannon, who talked to Ella O’Dwyer about her own experience of internment.

What year were you arrested?

I was arrested on 3 March 1973. I was 18 years of age and was held for five days and then I thought I was going home. Of course I wasn’t [laughs]. I was heading for Armagh Jail. I was taken from our house in Turf Lodge at the early hours of the morning. None of the others in the family were lifted. My dad said that morning – ‘say nothing’. I took his advice. I got a bit of a pushing about and one cop – my dad had warned me about him – he was called Harry Taylor – a veteran of brutality, said he’d come down to the cell and rape me. He didn’t, but I was afraid.

How at 18 did you cope with that kind of aggression and how was Armagh?

In God’s truth I said, I’m not going to let it annoy me, and I knew there were republican POWs in Armagh ahead of me – Liz McKee and Tish Holland were there. Tish was only 17 when she was interned and then there were eight republican POWs in Armagh too. The OC was Eileen Hickey. Sadly, Eileen died in recent years. I learnt so much in Armagh about life, discipline, values and how to live with other people. We kind of leaned on each other and I made a lot of friendships in jail then – people I still know to this day.

Do you think the Irish Government could have done more to counteract Internment?

I feel the Irish Government let us down back then. In 1970, eight months before it was introduced by Faulkner, Jack Lynch, the then Taoiseach, and his Justice minister Dessie O’Malley announced that the Irish Government was preparing to introduce internment in the South. In the event, they decided against it but the announcement was later used by the Stormont premier to justify bringing in internment in the North.

What did you do when you came out of jail at 20 and how did internment impact on your life later on?

I spent two years in jail and it did take away part of my youth. My dad and my brother were also interned, so it was hard on my mother. She went to the rallies against internment – she was great. But you must remember that while I was in jail, I had POW status. We turned a bad situation into a good one, as they say, and we studied.

I’m a counsellor now – not a political councillor – I work in the area of suicide support and with victims of sexual abuse. I have a very happy life now. I didn’t let jail ruin my life but it took away some of the important years.

It is estimated that something in the region of 1,981 people were interned at that phase of the struggle. Were there many loyalists interned?

Internment went on until December 1975. It was a weapon traditionally used to put down republicanism in Ireland but in fact it had the opposite effect and actually led to increased support for the IRA. Out of almost 2,000 internees, only around 107 loyalists lifted. That speaks for itself.

Do you think there has been progress in the North in terms of relations between the two main communities?

Yes, things have moved on. I remember the bigotry of unionism back at the time when I was growing up. When I was 15, I left school and took my first job as a junior clerk with an agricultural firm. I remember one day serving tea to some of the other staff. One of them refused the tea and said he didn’t drink ‘holy water’. When I told my boss about it, he said I’d better leave. But I’m by no manner or means a bitter person. I feel, for instance, that the loyalist community haven’t nurtured themselves enough all along. They never really took the chance to learn or study and I think they are only doing that now.

In the period of 30 years of what is loosely called ‘the Troubles’, the republican struggle has had many traumatic phases. Do you think there is a tendency for us to lose sight of the memory and relevance of internment?

Maybe. But for the people who were directly affected the memory is alive. I think we need to recall that period – internment – and the injustice that was involved. As I said, it didn’t ruin my life, but it took away some of my youth and the internment of my father, brother and myself was hard on my mother. The families of all the other internees went through the same.

It’s important that people throughout Ireland be made aware of the consequences of internment and that we do all possible to ensure it never happens in this country again. It’s important to remember, recall and look at what happened back then.