19 August 2021 Edition

Unionism cannot cope with its loss of dominance

I think the last time I wrote for An Phoblacht was as a spokesperson for the Belfast Rape Crisis Centre in 1984. I wrote about what our work with women from all over the North was telling us about the prevalence of sexual violence against women and children, and how, contrary to the myth that strangers were the threat, it was largely being carried out within families and within communities. I mentioned the metaphorical rape of Mother Ireland by British John Bull and concluded that in any new Ireland women needed a commitment that there would be “no rape of Irish women...by Irish men.”

The piece got me into trouble with the UDA to begin with - this was quickly resolved when I wrote a matching piece for Ulster magazine. Then 30 years later, it was resurrected by a DUP politician who claimed on the basis of a misreading of what I had written that the BBC should not have me on its programmes.

My book “Northern Protestants - An Unsettled People” was published in 2000, when the Good Friday Agreement was new, and memories of the relentlessly violent years of conflict were raw. There was relief, hope for better times ahead. There was generosity and even a dash of magic. There was also sorrow and anger, and there was reason to fear that sectarianism would persist.

When I wrote a new introduction for the 2007 edition of the book, I quoted the broadcaster David Dunseith who said he sensed “a beginning of the green shoots of maturity” in the Protestant community. I also quoted the Progressive Unionist Party leader, David Ervine, who said there was less bitterness, less fear, and that: “We have become a more settled people.”

In 2000, I used the term, “the people I uneasily call my own”. My book’s harshest critics inevitably called me a Lundy, and, a term I had not heard before, a “guilty”, meaning someone ashamed of my own people and therefore cringing before its enemies. I was accused of not caring about the onslaught of violence that the IRA had directed at my community.

In the course of one radio discussion, a prominent unionist managed to call me both a “wee girl” and a Goebbels. But I also found many allies and, in the years that have followed, I have seen a new confidence grow among people from a Protestant background who no longer accept the old divisions here, the old banishings, the old assumption that if you criticise from within, you are a traitor. Far from wanting to defend and maintain, they want change. They identify with movements that are national, international and global.

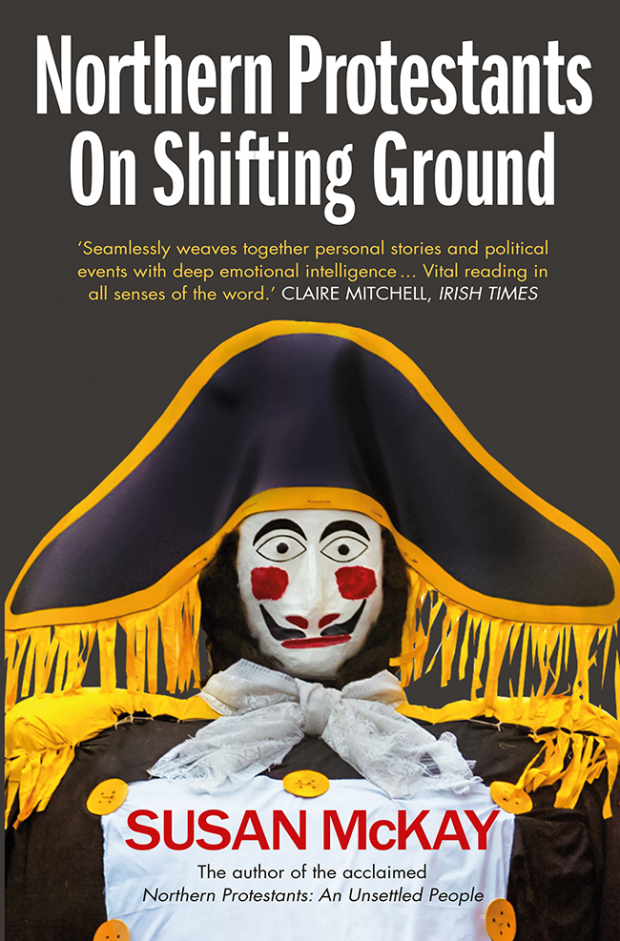

By the time I came to write my new book “Northern Protestants - On Shifting Ground”, I had become reconciled to my Lundification. In fact, I highlighted the voices of people from a Protestant background who have been excluded or rejected or have simply not been heard. The book has been well received, though not by elements of political unionism about which it is highly critical. This comes as no surprise.

In this centenary of the Northern Irish state, it has become clear that unionism does not know how to cope with its loss of the dominant position it used to take for granted. The DUP and elements of loyalist paramilitarism are consumed by nostalgia. Unionist leaders have failed to demonstrate the imagination and generosity that would be needed to transform the North.

They have not even tried to persuade republicans and nationalists that they truly want to share power. Instead they have wheeled out old militaristic clichés about coming out fighting, or said, like Arlene Foster, that if there was to be a United Ireland she would just leave.

Unionism’s state of disarray is nowhere more apparent than in its plea to the indifferent - verging on hostile - British government that all it wants is to be treated in exactly the same as the rest of the UK, while simultaneously refusing to implement UK law on, notably, abortion, claiming it is an imposition.

This belligerent weakness within unionism coincides with demographic changes which may well see the Protestant community become a minority. Sinn Féin is growing and there is a resurgence of energy and positivity in the SDLP. The conditions for a border poll will probably be met within the next decade. (Whether we can count on the British Secretary of State to instigate it is another matter entirely.)

However, my book is also, I think, likely to challenge republicans. Not because of the capacity of loyalists for renewed violence - which has been exaggerated, but because one of the themes that runs through the book is the deep pain that was, and is still, experienced by victims of IRA violence. The voices of people from a unionist background who were bereaved must be heard and responded to with imagination rather than well-worn formulas about all sides having suffered. Republicanism has to face up to the fact that there was an ugly strand of sectarianism in what it calls “the armed struggle”.

This book takes its title from something the poet and unionist Jean Bleakney said to me while we were walking along the border between her late father’s home in Co Fermanagh and Co Leitrim. Her father was a customs officer. She said that, in 2017, she had voted for the first time for the DUP. She had panicked, she said. “I felt the ground shifting...” Unionism, she said, was feeling “aggrieved, isolated and anxious” and it was losing ground in the face of Sinn Féin’s confident north and south republicanism.

Many Protestants I spoke with were open minded about the constitutional future. But everyone is going to have to be willing to change if there is to be a new Ireland, including those who most ardently aspire to it. The Republic as currently governed is no fit place for anyone who believes in equality or human rights. Above all, republicans must do everything possible to demonstrate that they would never treat a Protestant minority, or any other minority, in anything remotely resembling the outrageous way that unionism, in its heyday, treated the Catholic minority in the North. That ground has, thankfully, shifted for all of us.

Susan McKay is a journalist and author