28 October 2021

Negotiations in London 100 years ago

Remembering the Past

• The Irish delegation

As autumn turned to winter in 1921 negotiations were taking place in London that were to shape the destiny of Ireland for decades and the consequences of which are still felt today. The Irish delegation in London represented Dáil Éireann, the government of the Irish Republic, and they faced negotiators who saw themselves as representing not just the British government in Westminster but the British Empire.

Formal negotiations began on 11 October but the preliminaries had begun four months previously on 11 July, the day the Truce came into effect in Ireland. The first meeting between the President of the Irish Republic Éamon de Valera and the British Prime Minister Lloyd George took place in 10 Downing Street on 12 July. Eight days later the British presented proposals for a treaty that would see Ireland “within the Empire…in allegiance to His Majesty’s throne”, with Partition and the recently established ‘Northern Ireland’ parliament to remain in power in the Six Counties, full access to Irish ports for the British navy, facilities for their air force, recruiting to the British Army to be allowed and Ireland to share the burden of British war debt.

De Valera rejected these terms and said he would not present them to the Dáil. Lloyd George threatened to resume Britain's war in Ireland, as he was to do repeatedly during the negotiations. In a further formal response on 10 August De Valera said Ireland must be “free from Imperialistic entanglements” but would give Britain “reasonable guarantees not inconsistent with Irish sovereignty”. While Ireland as an independent state could enter “a treaty of free association with the British Commonwealth group” he made clear “we cannot admit the right of the British government to mutilate our country”.

Main questions were subject to approval of the Cabinet in Dublin and “the complete text of the draft treaty about to be signed will be similarly submitted to Dublin, and reply awaited”

The word ‘coercion’ was to feature much in the negotiations, mainly in relation to the Six Counties, with the British claiming Unionists could not be coerced and the Irish claiming they had no wish to do so. In replying to de Valera Lloyd George said the British could never acknowledge the right of Ireland to “secede from her allegiance to the King” and accused the Irish side of wishing to “coerce another part of Ireland to abandon its allegiance to the crown”. However, the greatest obstacle facing the Irish negotiators, apart from British insistence on the crown and Empire, was the fact that the British government had already put in place the Unionist regime in the Six Counties under the 1920 Government of Ireland Act and had done so with coercion. The paramilitary Special Constabulary was founded in November 1920, well before the setting up of the Six-County parliament. Pogroms against nationalists had taken place in 1920 and again in 1921 and more were to follow.

• President of the Irish Republic Éamon de Valera

And it was not only Lloyd George who was making threats. Tory Minister F.E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, on 19 August said that if negotiations broke down the British would be “committed to hostilities on a scale never hitherto undertaken by this country against Ireland”. Like other Tories in Lloyd George’s Coalition Cabinet, Smith had played the Orange card during the Home Rule crisis 1912-1914, and was committed to backing the new Orange state to the hilt. That said, the British had to be seen to negotiate and to appear reasonable to world, especially American, opinion. Winston Churchill said a settlement would remove “the greatest obstacle which has ever existed to Anglo-American unity”.

After much further correspondence de Valera wrote to Lloyd George on 30 September 1921 and accepted his invitation to negotiations in London on this basis: “How the association of Ireland with the community of nations known as the British Empire may best be reconciled with Irish national aspirations.”

While Ireland could enter “a treaty of free association with the British Commonwealth group” he made clear “we cannot admit the right of the British government to mutilate our country”

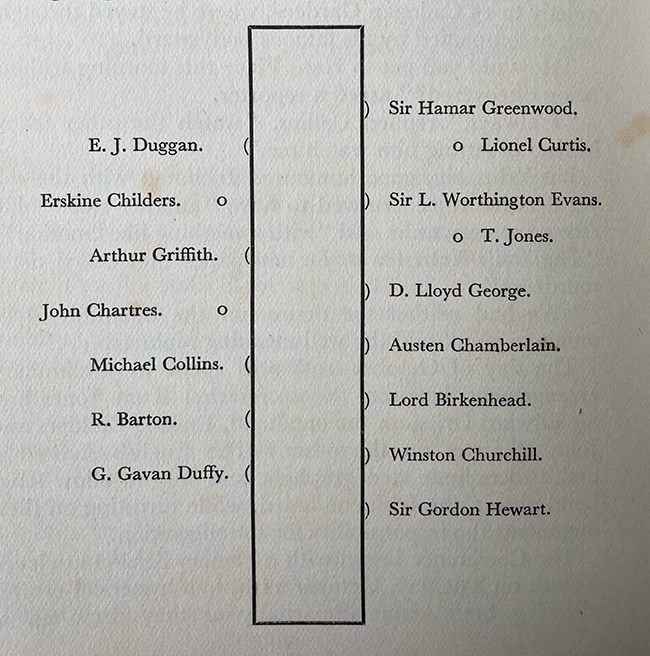

The Irish delegation was Arthur Griffith, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Michael Collins, Minister for Finance, Robert Barton, Minister for Economic Affairs, Éamonn Duggan TD and George Gavan Duffy TD. The main secretary to the delegation was Erskine Childers TD. The Dáil Cabinet gave the delegations its credentials as Envoys Plenipotentiary from the elected Government of the Republic of Ireland to negotiate and conclude on behalf of Ireland, with the representatives of His Majesty George V, a treaty or treaties of settlement, association and accommodation between Ireland and the community of nations known as the British Commonwealth.

Much has been written and debated about the decision of de Valera not to lead the delegation to London. Undoubtedly it was a weaker delegation without him and its task was more difficult. But what is often forgotten is that the Irish delegation was given a very clear set of instructions. All decisions on main questions were subject to approval of the Cabinet in Dublin and “the complete text of the draft treaty about to be signed will be similarly submitted to Dublin, and reply awaited”. When the crucial moment came this key instruction was not followed by the Irish delegation, with disastrous results.

The formal negotiations between the two delegations began in Downing Street on 11 October 1921. The British delegation consisted of Prime Minister Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead (Lord Chancellor), Worthington Evans (Secretary of State for War), Winston Churchill (Secretary of State for the Colonies), Austen Chamberlain (Leader of the House of Commons) and Hamar Greenwood (Chief Secretary for Ireland). Republican historian Dorothy Macardle described them as “dominated by traditions of disingenuous diplomacy, by inherited conventions and the rules of the old political game of skill”.

• Seating plan at the negotiations in 10 Downing Street

The approach on the Irish side was to offer the British all guarantees consistent with Irish independence. Ireland would be a neutral state and would not do anything to threaten British security. Ireland would freely enter an ‘external association’ with the British Empire, again consistent with Irish independence, in order to address the British preoccupation with the crown. The essential unity of Ireland would be maintained but the Irish side was prepared to offer the Unionists the option of a regional parliament remaining in place under an all-Ireland parliament. The question of Partition was central to the negotiations and was not a ‘done deal’ by any means from the Irish point of view. Delegations of nationalists from the Six Counties made repeated visits to Dublin during the negotiations stating their determination not to be corralled in an Orange state.

Lloyd George’s political skill was as an arch-manipulator and confidence trickster. He had already used these skills in relation to Partition. In 1916, a few days after the last Easter Rising executions in Kilmainham Jail, Lloyd George wrote secretly to Unionist leader Edward Carson on the proposed ‘provisional period’ of exclusion of Ulster from Home Rule: “We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland.” At the same time Lloyd George was assuring nationalists that any Partition arrangement would only be temporary. Nationalist leader John Redmond fell foul of this duplicity and it was one of the factors leading to the defeat of his Irish Parliamentary Party by Sinn Féin in 1918. Now Lloyd George would attempt the same trick again.

• Michael Collins leaving Downing Street, London

After a series of plenary meetings the negotiations were conducted in sub-committees and then personal meetings were introduced. This facilitated Lloyd George in weakening and dividing the Irish side. The last plenary was held on 24 October and after that Lloyd George and Churchill met Griffith and Collins in private conferences. The British were insisting on allegiance to the crown while hinting that if this was given they would insist on the Unionists coming in under an all-Ireland parliament. This was the bait with which Lloyd George now tempted Arthur Griffith.

On 27 and 28 October 1921 the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis met in Dublin's Mansion House. De Valera reported on the negotiations and said that they must be prepared for a breakdown and the war that might follow. They would not be accepting allegiance to the crown but were prepared to enter some form of association with the states of the British Empire.

Lloyd George used his own parliamentary position as a form of pressure on Griffith. He led a coalition government consisting of Tory Unionists and a section of Liberals. Tories opposed to the negotiations with the Irish put down a House of Commons motion of no confidence in the Prime Minister on 31 October. In November a major Unionist rally was due to be held in Liverpool. Lloyd George sought personal assurances from Griffith that he would not oppose recognition of the crown and Empire and Irish facilities for the British navy, in other words a closer approach to the British position than that agreed by the Dáil Cabinet, in return for pressure on the Unionists on Irish unity. Griffith agreed to provide these assurances and wrote to Lloyd George accordingly. Robert Barton and Gavan Duffy were alarmed and opposed to this course of action. Duffy crossed to Dublin to express concern at the way the negotiations were being handled by Griffith and Collins. But nothing was done and the scene was set for the final act of the tragedy.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures