20 May 2021 Edition

Fleet Street and the hunger strikes

In the spring of 1981, Fleet Street, traditional home of the newspapers that helped to set Britain’s political agenda while dominating its national conversation, was all of a flutter at a coming royal wedding.

There were more serious distractions. Riots broke out in Brixton, Peter Sutcliffe (aka the Yorkshire Ripper) was on trial, the British Labour Party was in crisis, and Ireland’s greatest-ever footballer, George Best, entered hospital in another vain bid to win his battle with the bottle.

As ever, the popular press averted its gaze from the situation in the North of Ireland, the place it chose to call Ulster or, just as infuriatingly and wrongly, the Province. So, the start of a second hunger strike by prisoners in the H Blocks passed with barely a paragraph.

On 2 March, The Times, which cast itself as the paper of record, was a model of restrained formality: “Mr Robert Sands, described as leader of the Provisional IRA men at the Maze prison, began his threatened hunger strike yesterday.”

The Guardian, servant to the nation’s liberal minority, carried the longest of articles that morning to report that Bobby had refused food for the first time. It was written by its Belfast-based correspondent, David Beresford, who would later become the hunger strike’s most illuminating chronicler with his book, ‘Ten Men Dead’.

A couple of paragraphs appeared in the Daily Telegraph. Nothing in the Daily Express or The Sun, a brief in the Daily Mail, 31 words in the Daily Mirror. I was working for one of the papers that also ignored the event, the newly-launched, supposedly left-of-centre, red-top tabloid, the Daily Star. At the morning news conference, the hunger strike was not regarded as newsworthy enough to merit a mention.

At the time, the joint sales of those eight daily papers amounted to 14.7 million copies a day. Their total readership was estimated at three times that, about 44 million, a huge slice of the UK’s then population of 56 million. Of course, the national press was not the British people’s only source of news. There were the bulletins across BBC TV and radio channels, plus the ITV service. But it was newspapers that dominated the media landscape. What they reported, what they didn’t report, and, most significant of all, how they reported, was of paramount importance.

From 1969 onwards, the papers, whatever their political persuasion, had misreported, misinterpreted, and misrepresented the IRA’s struggle. Its members had been marginalized and demonised. In so doing, editors blinded themselves, and their readers, to the true situation on the ground in the Six Counties. As willing allies of successive British governments, Labour and Tory, they believed instead that their own propaganda reflected reality.

This denial of the potency of Irish republicanism was evident in their collective reaction to the beginning of the 1981 hunger strike. It was of no real concern. It was “proof” that the IRA was losing the war (although, of course, they pretended it wasn’t a war). Most definitely it was not “news.” For news was what those newspaper editors said it was, and they didn’t regard a prison protest in “Ulster” as news. End of story.

Press neglect of Northern Ireland, and the consequent ignorance of its readership, had a long history. From Partition until the Civil Rights protests in 1968, there was no scrutiny of its Stormont government. Unionists, safe from inquiring journalists, did as they liked. Once the Troubles arrived, newspapers - acting in concert with the British authorities they were supposed to scrutinise - conveniently overlooked the half century of despotism to portray the resulting complexity of political, economic and social division in the simplest of terms. It was a conflict between two warring tribes, they said. And they chose to side with the tribe that wished to maintain the Union regardless of its previous crimes.

That background is essential to understanding not only the lack of support for the IRA within Britain but the lack of knowledge about the conflict, which persists to this day. In 1981, despite Margaret Thatcher’s two-year-old government becoming ever more unpopular week by week, there was one subject on which she and every British newspaper editor could agree: the IRA must be defeated.

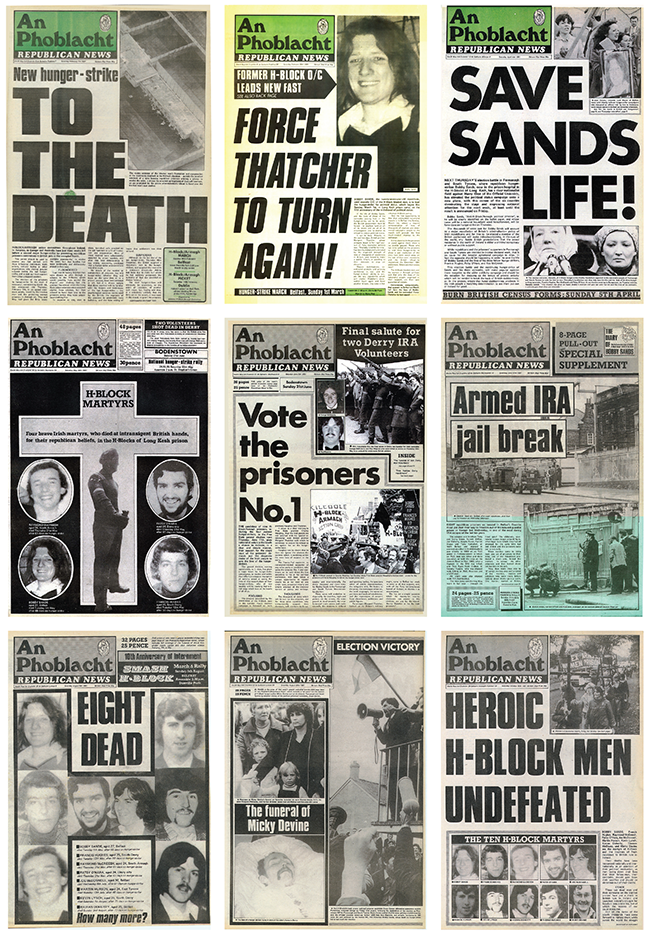

Coverage of the hunger strike was a classic example of how a compliant media operated as a propaganda arm of government. First stage: ignore and belittle. Throughout March, the absence of news articles about Bobby’s fast, even when he was joined by other volunteers, was striking. Editorials, such as there were, backed the government’s line that prisoners should never be granted political status. The message to readers was obvious: the hunger strike was a matter of no consequence. Nothing to see here, move on.

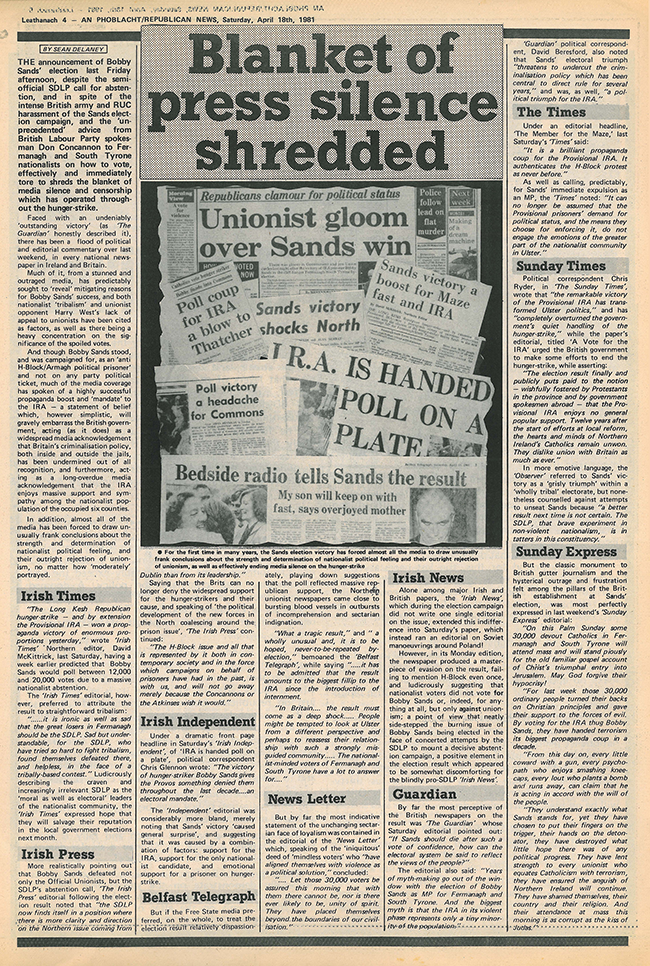

A similar silence greeted the decision, on 26 March, by Bobby to stand as a candidate in the parliamentary by-election for Fermanagh/South Tyrone. Once the other potential candidates dropped out, creating a straightforward battle for votes between Bobby and the Unionist, Harry West, only The Times, The Guardian, and Daily Telegraph thought it merited coverage. On 31 March, all three reported that Bobby was likely to win. The mass market titles kept quiet.

But, as polling day neared, the Daily Express confidently predicted that “sufficient Catholic voters will abstain” to enable West “to scrape home to victory”, which “will be a major blow for the IRA propaganda machine”.

But Bobby’s election victory on the 40th day of his fast could not be ignored. The Express carried the news on its front page, as did the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail. Rightly, the Mirror viewed it as a major boost to the prisoners’ campaign for political status. The other papers refused to admit that truth. So, at this point, we entered stage two of media mendacity: turning reality on its head.

Nowhere was this clearer than in The Times, which asserted that the vote had no especial political significance beyond “expressing sympathy for Sands and concern over conditions at the Maze” and merely amounted to “a rejection” of his opponent, West. It concluded: “The myth of Fermanagh must not be allowed to gain credibility.” When I first read that 40 years ago, I was struck by both its impotence and its arrogance.

What convinced the myth-making editorial hierarchy of The Times that anyone in Ireland either cared for its opinion or would take heed of its “advice”? Who did the paper think would stop a unique IRA-inspired electoral victory, soon to be repeated when two prisoners were elected to the Dáil, from gaining credibility?

I looked in vain among my colleagues for even a glimmer of sympathy, let alone understanding. For them, for the overwhelming majority of Britons, Northern Ireland was a mystery they could not understand, a riddle they didn’t wish to solve. There were honourable exceptions, however, such as the 500 people who decided to defy a government ban on marches by planning to march on Downing Street. They were set upon by police as they gathered outside Kilburn tube station. Thirty two of them were arrested. Some managed to get to Westminster, but were foiled by police cordons.

Meanwhile, newspaper editors, apparently oblivious to their own propagandistic role, were obsessed with the possibility of republicans securing a publicity coup in the event of Bobby’s death, which was the fervent wish of the Sunday Express editor John Junor who wrote: “I will shed no tears when Sands dies. My only hope is that if and when he does every other IRA terrorist will go on the same sort of hunger strike in sympathy. And stay on it until they are all in wooden suits.”

This belligerent, bloody- minded point of view wasn’t regarded as the least bit controversial among his audience. And I heard many a journalistic colleague say much the same, often worse. Irish republicans were The Other. After years of being misinformed about the nature of the struggle in Ireland, British people believed in the oft-repeated media myth that the IRA was a small “terror group” without much support and in the process of being rapidly defeated.

In Fleet Street, as in Britain, there was no grasp of the implications of a government allowing the hunger strikers to die. Thatcher’s soundbite rebuke to prisoners demanding political status - “a crime is a crime is a crime” - was accepted as a reasonable response. The Express told its readers that “decent Irish people revile them [the hunger strikers] as a stain on their country’s honour.”

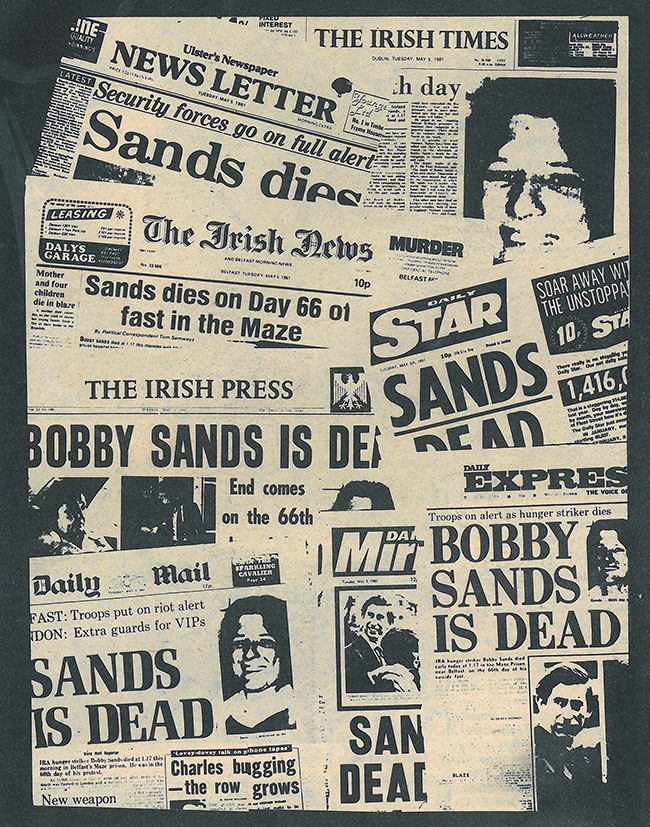

When Bobby finally succumbed on 5 May, the third stage kicked in: derision and denial. “Blackmail has failed,” said the right-wing Sun. “The society which has stood firm against violence in long blood-stained years will remain unshaken.” Its left-of-centre rival, the Mirror, agreed. A hunger striker’s death “advances no cause.” And so said the Express: “Sands will find no victory in the grave… The shadow of Bobby Sands will pass.”

A Guardian writer was unsympathetic, seeing Bobby’s self-sacrifice as “a bizarre mixture of heroism, idealism, criminality and black comedy.” In conceding Bobby’s bravery, the Telegraph regarded it as “the courage of the ruthless and corrupted sort that holds human life in contempt.” For the Express, he was simply “a fanatic.”

In their London offices, the editorial executives of Britain’s press preached the gospel according to prime minister Margaret Thatcher. They danced on the graves of Bobby and the other nine hunger strikers who followed him to their deaths. They were convinced that their words counted.

Of all the papers, it was The Times, by relying on the reports of its Belfast correspondent, that was able to perceive the real effects of the hunger strike, noting that it had stimulated “a measure of active sympathy with the Provisionals that has not been seen since the army shot thirteen men dead in Londonderry in January 1972.”

How different from the Daily Telegraph leader writer who so confidently pronounced that hunger striking “normally fails to procure lasting fame for those who employ it.” Really? Forty years’ on, whose iconic portrait stares down from the walls of Belfast and Derry? Whose name is synonymous with the hunger strike that proved to be the starting point for the Peace Process? Who defeated the propaganda perpetrated by Britain’s mighty national press?