20 May 2021 Edition

A watershed year in the freedom struggle

1981 was a watershed year in the freedom struggle. It was the year which saw the incredible and prolonged battle in the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s prison for political status reach an unimaginable zenith of nobility, heroism, and determination when ten young men died on hunger strike.

The deaths of the hunger strikers effectively defeated Margaret Thatcher’s sustained attempt to criminalise the republican struggle and elevated it onto a new moral and political plane.

The formidable resources invested by Thatcher in her criminalisation campaign failed to impinge on the political legitimacy of the republican struggle which was embedded in a centuries old resistance movement for national independence – which the protesting prisoners courageously symbolised.

For five years, living in the most appalling, inhuman, and brutal conditions, these brave men and women, IRA and INLA volunteers on active service, in the front line of a literally life and death struggle, protected the integrity of that struggle with nothing more than their bodies and unconquerable minds – fortified and imbued with a simple, yet profound idea – the freedom and independence of Ireland.

1981 was also the year which saw for the first time, in this phase of the freedom struggle, the tactical use of elections by republicans to advance the prisoners’ cause.

The significance of this electoral intervention is to be found in the speed with which the leadership of the party decided to embrace elections as a central and key strategy to advance the struggle for a united and independent Ireland.

This swift move reflected the realisation at leadership level of the positive impact of the election results, in the first instance on the prisoners’ campaign and secondly on the freedom struggle, nationally and internationally.

On the day Bobby was elected, I well recall being in a friend’s house at the same time a senior IRA figure was passing through, whose response to the nine o’clock British news that Bobby was elected was that it ‘was worth ten bombs in London’.

As the convoy of ten coffins emerged from the prison hospital, beginning with Bobby Sands on 5 May and ending with Mickey Devine on 21 August, dramatic election results peppered the tragedy and sadness of the hunger strikers’ deaths and of those on the streets of the North, where over 60 people died.

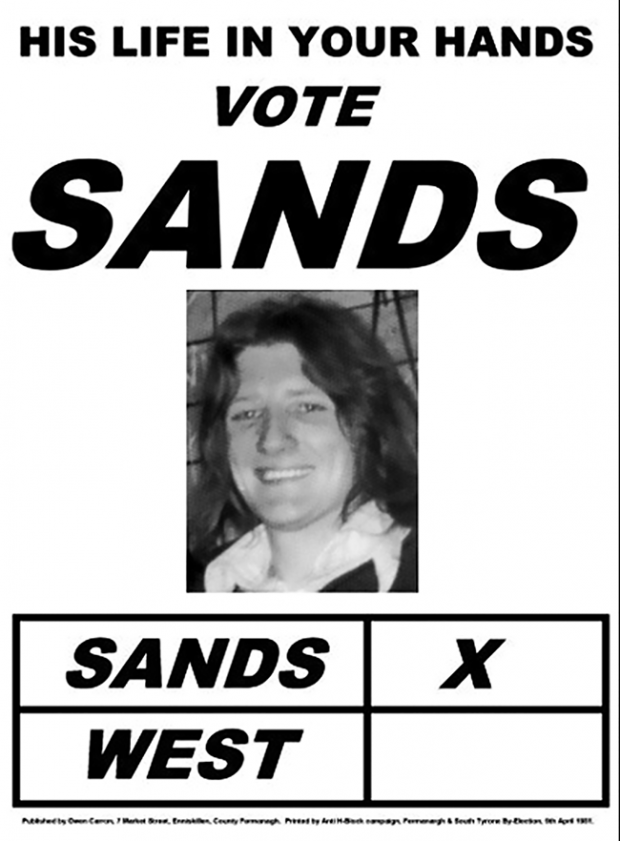

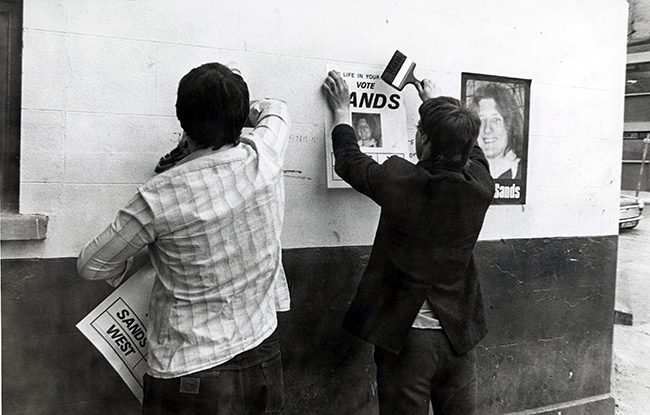

The idea to stand Bobby as an election candidate struck me almost instantly when I heard the sad news of the passing of Frank Maguire MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. He was a great friend and supporter of the prisoners’ cause. He was a former political prisoner himself in Belfast’s Crumlin Road gaol in the 1950s.

• The formidable resources invested by Margaret Thatcher in her criminalisation campaign failed

I discussed the idea with Gerry Adams and we in turn discussed with Bernadette Devlin McAliskey – out of which the wheels were set in motion to have Bobby nominated as a candidate.

Bobby Sands election victory in Fermanagh and South Tyrone on 9 April was followed with election victories on 11 June in Cavan-Monaghan and Louth when hunger striker Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew, a ‘blanketman’ prisoner, were elected TDs. Other political prisoner candidates stood in several constituencies across the south and received significant electoral support.

Taken collectively, the intervention by political prisoners in the 26-County election deprived Fianna Fáil of its stated objective of forming a government with an overall majority. Tellingly, this was the start of coalition governments and an end to single-party government.

It was ironic that it was support for republican political prisoners at the ballot box that deprived the outgoing Fianna Fáil government, led by Charlie Haughey, of its overall majority objective, given its abysmal failure to prevent the deaths of the hunger strikers or meaningfully intervene on behalf of the prisoners and their relatives.

• Dramatic election results peppered the tragedy and sadness of the hunger strikers’ deaths and of those on the streets of the North, where over 60 people died

On 20 August, Owen Carron, Bobby Sands’ election agent, won the seat in the by-election held after Bobby’s death with an increased majority – a reflection of the anger nationalists felt at the death of the people’s MP.

In May of that year, the Irish Independence Party, Peoples’ Democracy, the IRSP, and a number of independents, standing in the local government elections on a pro-prisoner ticket, achieved significant electoral success. West Belfast MP and SDLP leader Gerry Fitt lost his Belfast Council seat to Fergus O’Hare of People’s Democracy.

Oliver Hughes, the brother of Francis Hughes, was elected and, in September, James Mc Creesh, the father of Raymond, was also elected at local government level.

Less than a year after the end of the hunger strike, Sinn Féin formally took part in its first election in the Six-Counties since the outbreak of the conflict in the late 1960s. Five Sinn Féin representatives, standing on an abstentionist ticket, were elected to the Stormont assembly, including Gerry Adams and Martin Mc Guinness.

In the years immediately before the remarkable events of 1981, Sinn Féin was debating whether to involve itself in elections, particularly in the North. The party had an abstentionist boycott policy with regard to Dáil, Westminster, Stormont, and local elections in the North, but it stood in local elections in the South.

The difficulty facing advocates for ending abstentionism on a selective basis, e.g. local government elections and assembly elections in the North, can be gleaned from the opposition to a motion that current MP for Mid-Ulster Francis Molloy put at the Ard Fheis before the 1981 hunger strike.

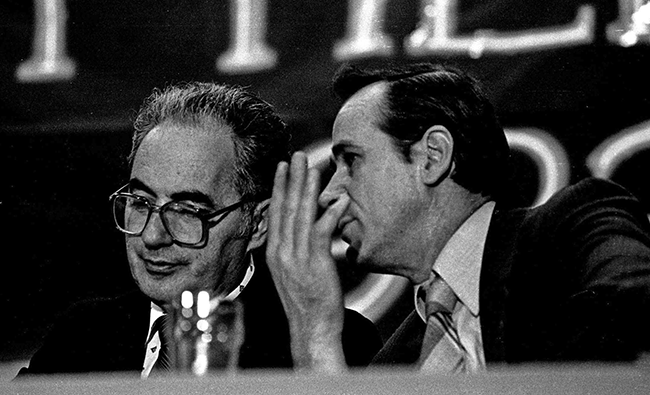

• Ruairi Ó Brádaigh and Dáithí Ó Conaill at the 1982 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis

Francis and Jimmy McGivern, on behalf of South Tyrone Comhairle Ceanntair, argued that the party should stand in the north and take their seats in local government elections. Ruairi Ó Brádaigh, then president of the party, spoke angrily against the motion saying that he would ensure that a motion of this nature would never again find its way onto the party’s Ard Fheis clár.

It was difficult to understand the logic of opposing Sinn Féin standing in local government elections in the North when the party stood in the local government elections in the south and took their seats. But, of course, the difficulty ran much deeper than the motion brought to the Ard Fheis by Francis.

It was a fundamental issue enmeshed in the history of the struggle for independence, going back to the 1921 Treaty and Partition, with the predominant outlook suspicious of being involved in elections in case it would ultimately undermine the use of armed struggle.

In a previous phase of the struggle, the ‘Border Campaign’ of the 1950s, two prisoners were elected to Westminster from the Mid-Ulster and Fermanagh-South Tyrone constituencies in 1955. Republicans won 23.6% of the ballots with 152,310 votes. In 1957, Ó Brádaigh was one of four abstentionist TDs elected in the Dáil elections.

It wasn’t a clash over tactics. It was a clash over the strategic development of the struggle which was summed up in the argument presented by Danny Morrison that armed and electoral struggle were complementary, not contradictory and that both should be pursued simultaneously.

This was famously characterised by Danny’s colourful phrase at the Ard Fheis in 1981 when he said, “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?”

The evolution of Sinn Féin’s involvement in elections was understandably slow and, at times, one is in awe at the position the party now holds in Ireland – in government in the North, the lead opposition party in the South, and on the cusp of being in government there following the next election.

And it all began in Bobby Sands’ cell in the H-Block’s prison hospital, where he agreed to stand as a candidate in Fermanagh-South Tyrone, where he heard the news of his outstanding victory and where he died 40 years ago on 5 May 1981 after 66 days on hunger strike.

Jim Gibney is a Republican activist, former political prisoner, and parliamentary adviser to Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile