20 May 2021 Edition

And still, they couldn’t break us

I was released from Armagh Gaol on 5 August 1981, three days before the death on hunger strike of Thomas McElwee. I left behind some of the bravest and best friends and comrades I have met during my long involvement in republicanism. The years leading up to and after the hunger strikes of 1980 and 1981 will forever be a part of me and what shapes me to this day.

There has been a lot written by historians and academics about that seminal period of Ireland’s long history of resistance to British rule. But, by far, the most important are the personal, first-hand, stories of those who were there, who lived through and witnessed these historic events in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and Armagh Gaol and on the streets of Ireland.

When the British Government announced in 1976 the removal of political status for Irish republican prisoners in the Six Counties and claimed that from then we were criminals, they, and we, had no idea of the consequences of that move.

I honestly don’t think they understood what they were dealing with. Their ambivalence towards the situation in the gerrymandered Six-County statelet and their unwavering support for the undemocratic system of governance exacerbated and prolonged the nationalist community’s desire to see it ended. For too long, discrimination and oppression had been the way of life for Catholics in a predominantly unionist regime.

The British and unionist government thought there was a military solution to an ages old scar that had festered and burned for far too long and they took the nationalist population for granted.

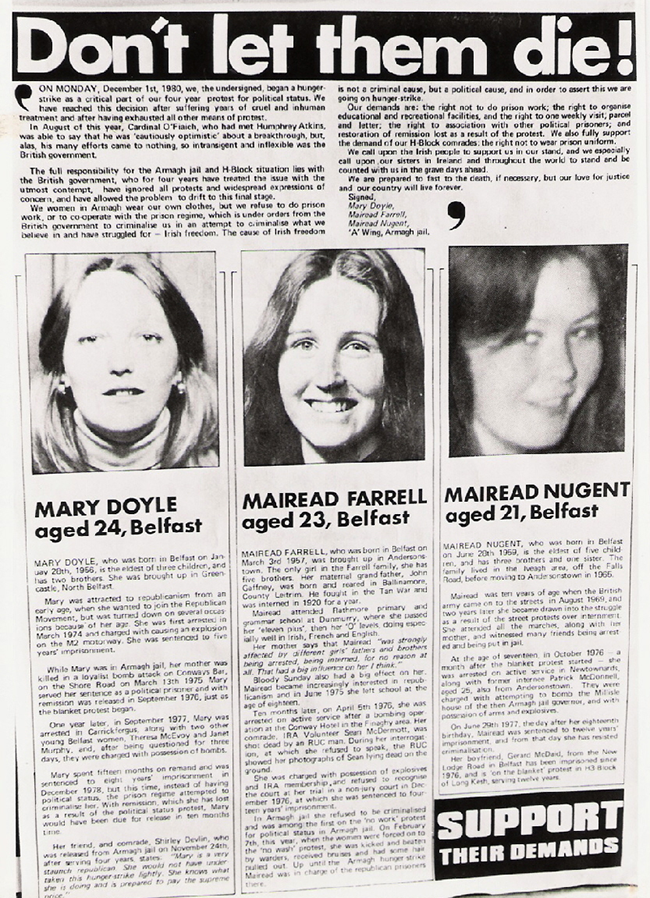

• (left to right) Eileen Morgan Sinéad Moore, Maréad Farrell (back) and Síle Darragh, Armagh Jail yard, 1980

Support for the IRA was growing and the British and unionist governments needed to find a way to break that resistance. They devised their ‘normalisation’ policy, the introduction of enhanced RUC patrols backed up by the sectarian UDR and even worse oppression visited upon the nationalist/republican population. They needed to ‘normalise’ the situation; to convince the world that this was a small local dispute and they thought us prisoners were the weak link.

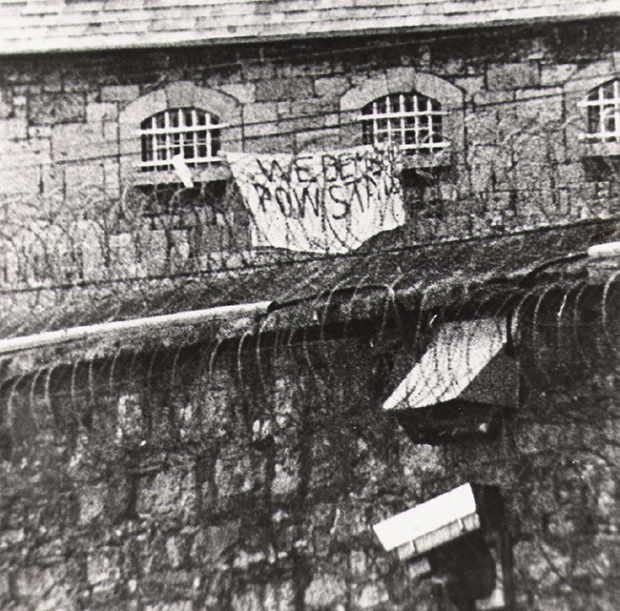

They underestimated us. We refused their labels and numbers, their beatings and savagery, the starvation and cold. We knew the struggle in the prisons were about more than wearing our own clothes and prison work. We knew their intention was to break the spirit of the very people we came from and to give in was to give them a victory, both militarily and psychologically.

We spent four long years denied all basic rights afforded to prisoners throughout the world. Very many served their entire sentences on protest after losing remission for refusing to work. We were denied letters, parcels, and visits. The men in the H-Blocks were naked in prison cells twenty-four hours a day because they refused to wear a prison uniform. Beatings were systemic, brutality became the norm. Physical and mental cruelty was a mark of some individuals, and many took pride in how belittling and cruel they could be. And still, they couldn’t break us.

Together, we were one. A slight to one of us was a blow to us all. They tried to single out those they thought of as weak. We circled around them and kept them strong. They tried everything. We resisted everything. Some of the petty things they did demeaned them much more than it did us. They showed us a cruelty and a mind-set that this world has seen too often, one that has seen torturers brought to court. They shamed themselves.

We resisted it all. But prisoners have only limited avenues of resistance; the next step was to be the final one. Too many had served full sentences on protest. Far more were facing many more long years in inhuman conditions. It couldn’t go on. We were at stalemate and the decision to hunger strike wasn’t taken lightly.

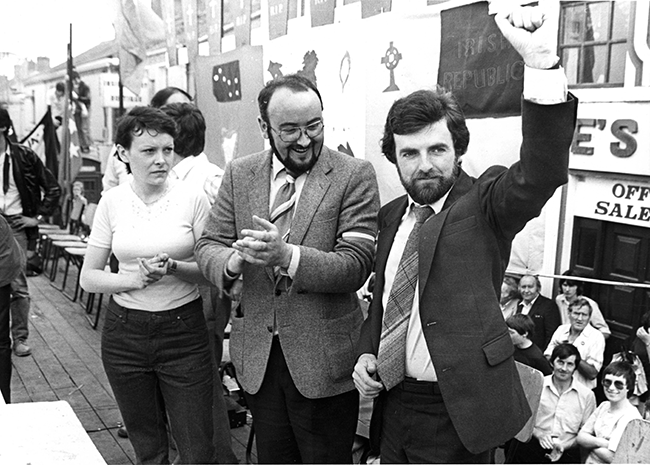

Those were dark days. There were highs when we clung to hope, like the election of Bobby Sands in Fermanagh/South Tyrone, and later Kieran Doherty in Cavan/Monaghan and Paddy Agnew in Louth, and there were many, many lows. We grieved their loss. We felt it as a physical pain, as deep and sore as losing a family member. They were our family.

• Síle with Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin and Owen Carron at an election rally for Kieran Doherty in Cavan/Monaghan, 1981

The bond between the POWs during that time was something that never could or will be seen again. We felt we knew them. We knew the names of their parents, brothers, sisters and children. We knew their cellmates and the yarns and craic they told, the stories they told and the songs they sang. They were a part of us, and our hearts broke at the loss of them.

But, they were also our pride.

What type of bravery is in a man to step forward and embark upon a long and painful death?

What does it take to stand alone and to use your own body as a weapon against those who have wronged you?

That takes a special kind of person.

The hunger strikers showed the world the strength of Irish resistance and set us on a path to changing the very nature of republican struggle. No longer could the British Government describe the north of Ireland as some kind of local quarrel between two competing sides. The world knew they were right in the centre of it. The hunger strikers put them directly in the gaze of the world and subsequent events have kept them there.

Times have changed. The struggle has changed and it is time to heal that deep scar.

I will never forget the period of 1976 to 1981. I will never forget those who died inside and outside the prisons to bring us to this point. I will never deny them and their memories. They are a part of us, a part of our history and we should be proud of them. And I hope to see the day when we can remember them all in a new and unified Ireland that embraces and respects all of its citizens equally. That is what they fought for. That is what they died for.

Silé Darragh is a Sinn Féin activists and former republican prisoner.