20 May 2021 Edition

Time to build a new Ireland, one without walls

• Seán Murray interviewing people for his documentary 'The Wall'

As we reflect on over 100 years of Partition, the Northern state progresses to a rapid decline. What was meant to be a centenary of celebration has instead become an annus horribilis for the leaders of unionism. The pincer movement that removed Arlene Foster was quickly followed by the sinking of submarine Steve and as we enter another long summer, the growing siege mentality exacerbated by the implementation of the NI Protocol leaves nationalist areas throughout the Six Counties vulnerable once again. With the onset of the marching season and growing discontent from working class loyalists on yet another betrayal by the British government, will we see this outplayed in a summer of sectarian attacks on their nationalist neighbours?

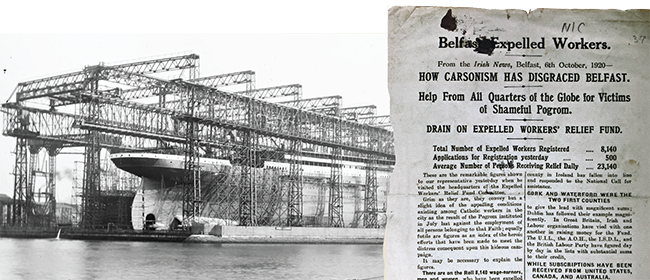

My own area, Clonard, has borne the brunt of many of these attacks, much of which increased in the years following Partition. Pogroms against Catholics were a common feature of Belfast during the nineteenth century as unionism sought to entrench its dominant position in the North. Partition in 1920 led to widespread violence and, between July 1920 and December 1922, over 300 Catholics were killed and over 11,000 forcibly forced from their jobs. 23,000 were driven from their homes, including my own great-grandfather’s family who were burnt out of their home in Turin Street, Belfast in 1920. Only months before, he was one of many Catholics forced from the shipyards and beaten by loyalist mobs. He suffered a serious head injury and never fully recovered.

In a recent documentary, I discussed the upcoming centenary through the prism of my own family tree where I detailed the story of my great-grandfather and the wider effects of Partition on following generations. His story is intertwined with that of my grandmother’s side of the family who were Protestant unionists from the Shankill Road. The film offers a backdrop to the complexities and trajectory of our individual cultural heritage.

• Catholics forced from their jobs and in the shipyards they were beaten by loyalist mobs

My great-great-grandfather, David Clifford, was an Orangeman and member of the British Army who became a full-time police reservist. Both families couldn’t have been more ideologically diverse, a disposition that became increasingly polarized as years went by.

The daughter of David Clifford, my great-grandmother Margaret (Maggie), married Geordie Cunningham, a Catholic from Norfolk Street in Belfast, thus ending the family tradition, a move that caused great hostility from locals on the Shankill Road.

The family home was no place for a mixed relationship and the move to a Catholic area offered a haven in what was a very turbulent time. After converting to Catholicism, the family set up home and had two daughters and a son, one of whom was Molly Murray – my grandmother. Her own life and that of her own children was to change dramatically when, in August 1969, history was to repeat itself.

On 15 August, rampaging loyalist gangs along with B-Specials once again attacked the Clonard area, burning many homes in Bombay Street, Clonard Gardens and Kashmir Road. A number of Catholic families were evicted from Cupar Street and their homes destroyed with two Catholic-owned off-licence premises looted and then burnt. Only for the swift action of locals in repelling the well-armed baying mobs, the towering Catholic Monastery would also have been burnt to the ground.

• August 1969 – the scene from Clonard Monastery

Clonard was irreversibly altered. The mental barriers imposed by the policies of a sectarian state were now manifested by the physical barriers on every street corner. The houses that had been destroyed in Cupar Street were exactly where the peace line lies now. This provided the first separation between both communities that saw the gradual and heightened construction of what is now known as the ‘peace wall’.

The events of 1969 politicised a new generation and the struggle that followed saw many local men join the IRA. My own father was one of a number of family members jailed during internment in 1971, a policy that witnessed many young men from the area imprisoned without trial. He was again jailed in 1981. I then spent many years travelling to Long Kesh with the children of other prisoners in the Sinn Féin-organised buses.

The 1980’s was my decade, the decade of my youth. On reflection, we were anesthetised by the conflict. We were the generation born into it and the many sectarian killings that occurred within the community was something we became accustomed to. We mourned for the loved ones of our friends and by the time we attempted to make sense of it there was another funeral or wake to attend.

In exploring the trajectory of my own family history, I am reminded of the course it has now taken and the suffering we have all endured to bring us to where we are now. The state that attempted to break the spirit of those before us is now being fractured by their sons and daughters. The Good Friday Agreement paved a new way forward for us all and the sectarian state that was built on undemocratic foundations would always crumble at the equitable demands of its people.

The resistance we now see to requests for historical redress by victims of state violence is one further attempt by unionism to control the narrative of the conflict. However, the official narrative is now gone, there aren’t enough buckets for the sinking ship. In April 1934, Prime Minister James Craig declared “All I boast is that we have a Protestant parliament and a Protestant state”. That project is gone, Partition has failed us all. It’s time to build a new Ireland, one without walls.

Seán Murray is an award winning film/documentary maker from Belfast. His documentary titled The Wall can be viewed at https://seanmurray.tv.