20 May 2021 Edition

The Road to Partition

The prophetic nature of these words by James Connolly published in the Irish Worker in March 1914, came to pass on the 23 December 1920, with the passing into law of the Government Of Ireland Act.

Civil War, repressive legislation, internment, discrimination, misogyny and the mistreatment of women and girls, emigration, gerrymandered electoral boundaries, 100 years of political instability and suffering, and two reactionary states were the children of Partition. To understand where Partition led us, we should understand how it first emerged as a policy objective of the British Government and Ulster Unionists.

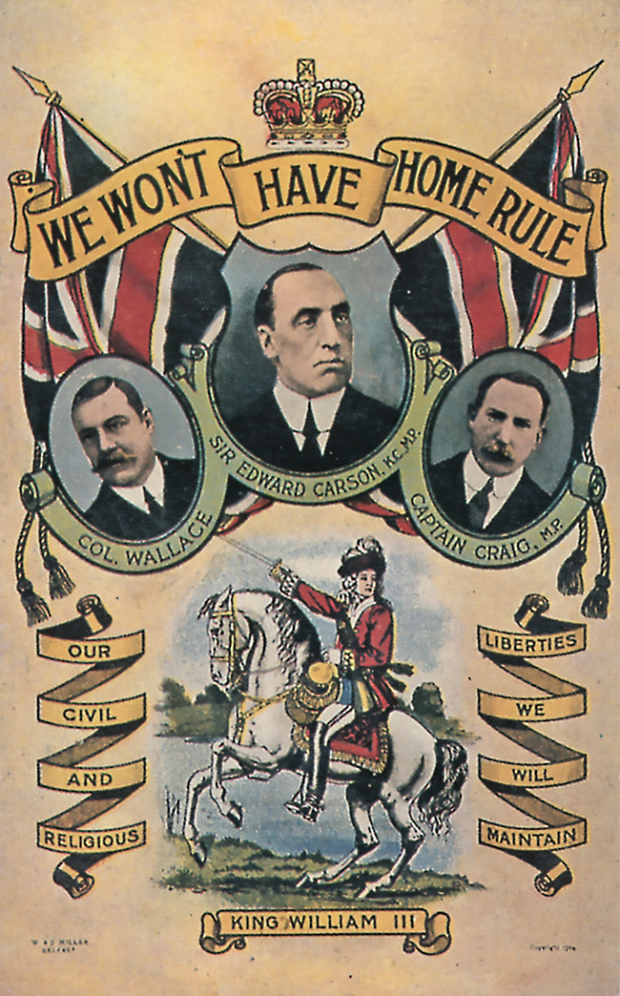

The genesis of Partition can be traced to the campaigns of opposition waged by Northern Unionist and the Conservative Party in Britain to Gladstone’s first Home Rule Bill in 1886. In these campaigns, four elements of Northern Unionism coalesced under the banner of the Orange Order. They were ‘Big House Unionists’, Protestant Industrialists, political clerics, the industrial working class and tenant farmers.

Beginning in 1886, the political conditions generated through their opposition to Home Rule, facilitated the growth and unity of Ulster unionism. What followed was the physical and psychological separation of Ulster Unionism from unionists throughout the rest of Ireland. Northern Unionists had consciously and deliberately created a defensive line across the map of Ireland based on their numerical, geographical, and religious strength in the nine counties of Ulster.

This led in March 1905, to the formation of a powerful centralized political organisation the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC). Between its birth in 1905 and the creation of the Northern State, the UUC would play a dominant and leading role in shaping the road to Partition.

From the introduction of the 1886 Home Rule Bill, the position of the nine counties of Ulster was raised in parliamentary debate. In his speech introducing the bill on 8 April, British Prime Minister Gladstone stated that, “various schemes” have been proposed, and that “One scheme is, that Ulster itself, or, perhaps with more appearance of reason, a portion of Ulster, should be excluded from the operation of the Bill we are about to introduce”, adding that, “What we think is that such suggestions deserve careful and unprejudiced consideration”.

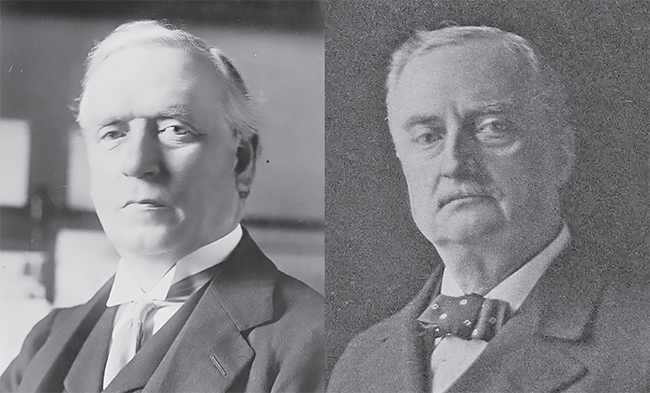

• David Lloyd George

Unionist opposition to Home Rule, supported by the British Conservative party, defeated the Home Rule Bills of 1886 and 1893.

In the 1910 British general election, the Liberal Party in Britain having lost their majority were dependent on the 74 seats of Irish Nationalists party to remain in power. Prime Minister Asquith came to an understanding with Redmond that a Home Rule Bill would be introduced if the Irish Nationalist Party supported his move to break the power of the House of Lords and support his budget.

This alliance between the Liberal and Irish Nationalist Parties galvanised the UUC and Conservatives. In early 1911 in the process of framing a Home Rule Bill, the British cabinet discussed a proposal by Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, to exclude some parts of Ulster from the Bill.

On 23 September, Edward Carson declared: “We must be prepared – and the time is precious in these things – the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant Province of Ulster.” Two days later, on 25 September, the UUC prepared a constitution for a Provisional Government of Ulster in the event of the imposition of Home Rule by Westminster.

In April 1912, the Home Rule Bill was introduced. During its journey through the Westminster parliament various amendments were made proposing opt-out clauses for parts of Ulster, all of which failed due to the difficulty of finding common agreement on the counties to be excluded. Despite their failure, the exclusion of Ulster was now firmly entrenched in the debate about the future of Ireland.

In September 1914, the Home Rule Bill became law, it was suspended until the end of the First World War. On 24 April 1916 when the Irish Republic was proclaimed at the GPO in Dublin, the political centre of gravity shifted away from London to Ireland.

• British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith came to an understanding with John Redmond that a Home Rule Bill would be introduced for support in his move to break the power of the House of Lords and to support his budget

The British Government sought to reclaim the political initiative. On 11 May 1916, Prime Minister Asquith announced Ireland was to get self-government (Home Rule); this announcement was followed by a further statement from Asquith, on 25 May that David Lloyd George, the Minister for War in the British Cabinet, was appointed to put the British Cabinet’s decision into operation.

After several separate meeting with Carson and Redmond in late May and early June, Lloyd George formulated a set of proposals, which advocated the immediate implementation of Home Rule with the provision that the six north-eastern counties be excluded. Lloyd George sold his proposal to Carson on the basis that Partition would be permanent. To Redmond the proposal was sold on the basis the outcome would be temporary.

Lloyd George had intentionally let the terms of the proposals, particularly the nature of exclusion, remain ambiguous. However, in a letter to Edward Carson on 29 May, Lloyd George wrote: “We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in with the rest of Ireland.”

On 6 June 1916, Carson spoke at a meeting of the UUC, and advocated acceptance of Lloyd George’s proposal to exclude the six counties. The meeting was adjourned until 12 June to enable Carson to confer with unionists from Cavan, Monaghan, and Donegal. At a reconvened meeting, the UUC accepted the proposition. At this meeting Carson dealt with the demographics which underpinned the decision. Ulster’s population contained 900,000 Protestants and 700,000 Catholics; But in the six-county area there would be 825,000 Protestants and 430,000 Catholics.

On 23 June 1916, John Redmond and Joe Devlin presented the same proposal to their Ulster supporters at a Convention in St Mary’s Hall Belfast where it was passed by 475 to 265. Redmond and Devlin believed that the Lloyd George proposals advocated ‘temporary’ exclusion of the six northern counties and therefore Partition of any sort was part of a war emergency act.

Eventually the contradictory proposals of Lloyd George were made public resulting in Carson and Redmond withdrawing from negotiations with the British Government. In December 1916, a crisis in the British cabinet led to Asquith’s resignation. Lloyd George became Prime Minister.

Lloyd George proposed an Irish Convention which sat in Dublin from July 1917 until March 1918. Sinn Féin boycotted the proceedings. By March 1918, the business of the Convention had halted, unable to reconcile the conflicting demands of its Nationalist and Unionist members.

The Convention failure was one of three major political reversals for the British Government in Ireland that year; Conscription was opposed and defeated by a broad spectrum of nationalist opinion, and 73 Sinn Féin candidates were elected in a December General Election, leading to the setting up of Dáil Eireann in January 1919.

Despite the clear mandate for Irish self-determination, the British Government moved ahead with its plans to Partition Ireland. On 25 February 1920, it introduced The Government of Ireland Bill. The Bill proposed the establishment of local parliaments in the Six and 26 Counties. The ‘Act to Provide for the Better Government of Ireland’, became law on 23 December 1920. The date fixed for the establishment of the two parliaments was 3 May 1921. Stormont’s first meeting was 7 June 1921.

• Crowds gathered outside Belfast City Hall in 7 June 1921 for the first meeting of the ‘Northern Ireland’ Parliament

Prior to the introduction of this new act the political crisis in the Six Counties intensified, underpinned by unionist paramilitary violence directed at the nationalist community. In June 1920, Derry’s nationalist community was subjected to sustained attacks from unionist paramilitaries, which led to 20 deaths, 15 of whom were from the nationalist community.

On 21 July, a meeting organised by the Belfast Protestant Association was held at the gate of the shipbuilders Workman Clark, in Queen’s Island, where unionist workers decided to expel their Catholic workmates from the shipyards. Many Protestant trade unionists were also driven from their employment. The expulsions spread quickly to other factories and mills across the city.

In the two-year period between 1920 and 1922, it is estimated that 11,000 Catholics were forcibly expelled from their workplace and 23,000 were driven from their homes. Thousands of Belfast Nationalists fled to the South of Ireland and over a 1,000 fled to Glasgow. Between July 1920 and December 1922, over 500 people were killed in widespread sectarian attacks in the City, including 300 from the nationalist community. All of this in a city where Catholics were 25% of the population.

The last word here should be left Edward Carson. On 14 December 1921 speaking in the House of Lords, he said “I was in earnest. I was not playing politics. I believed all this. What a fool I was: I was only a puppet and so was Ulster and so was Ireland in the political game that was to get the Conservative party into power”.

Tom Hartley is an author, historian and former Sinn Féin councillor.