20 May 2021 Edition

Saying 'No' to the low wage precarious economy

Covid-19 has further exposed what 40 years of neoliberalism has meant for our communities and economies—a debilitated local state struggling to respond to the public health emergency amidst a legacy of increasing inequality, disinvested public services, and decaying community infrastructure. Now, if there is to be anything other than a worsening of these long-running trends in a lopsided and unequal ‘Amazon recovery’, it is essential that we change course. Local economies must be rewired in service of people, place, and planet rather than for the extraction of profits by the wealthy few.

There are clear ways in which to do this. Recent years have witnessed an explosion of practical experimentation with alternative approaches capable of fundamentally transforming local economies by redirecting public resources to shift patterns of ownership and greatly improve distributional, environmental, and social outcomes.

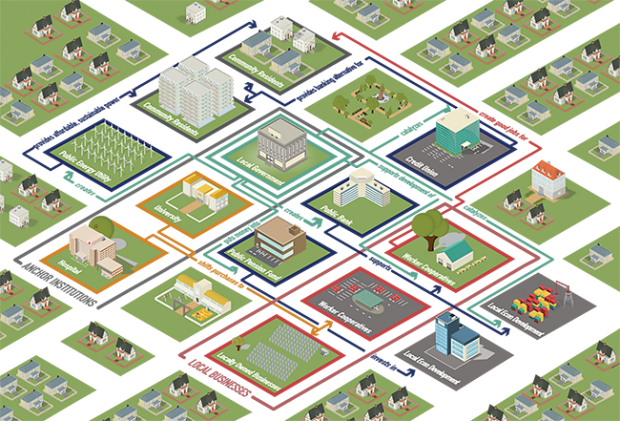

Relying not upon regulatory fixes or ‘after the fact’ redistribution but rather on deep structural changes to the economy, such approaches work through an array of institutions—including worker ownership, co-operatives, municipal enterprise, community land trusts, public banks, social enterprises, and more. They democratise the economy by broadening the ownership and control of capital. These approaches, and the institutional strategies for knitting them all together, have been termed “Community Wealth Building” (CWB).

CWB is emerging as a powerful alternative to neoliberal economic development. Offering real on-the-ground solutions for localities and regions battered by successive waves of disinvestment, deindustrialisation, and displacement, it is rooted in place-based economics, democratic participation and control, mobilising the untapped power of the local public sector.

The original model for CWB is in Cleveland, Ohio, in America’s rustbelt. The Evergreen Cooperatives were created in response to decades of economic destruction visited upon America’s manufacturing heartlands, part of an attempt to turn the tide. Cleveland had previously lost almost half its population and most of its Fortune 500 companies to capital flight, second only to Detroit in terms of poverty. Yet the city still boasted very large quasi-public institutions such as the Cleveland Clinic, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals—known as anchor institutions because they are rooted in place and aren’t likely to up and leave. Together, these institutions boasted a combined spending power of billions of dollars per year, very little of which stayed within the local community.

The ‘Cleveland Model’ involved bringing together the anchors in pursuit of a strategy of localising their procurement spending in support of a network of purposely-created green worker-owned businesses tied together by a community corporation. These included an industrial scale ecologically advanced laundry, a large urban greenhouse, and a renewable energy company.

A fund has recently been added to pursue employee ownership conversions of existing businesses. The Evergreen companies are structured so they cannot easily be sold outside the network without the permission of the community, and they return a percentage of profits to develop additional worker-owned firms. Unlike conventional corporations, these democratic businesses will not pick up and move their jobs elsewhere. They provide living wage jobs for their worker-owners, who also receive a share of their profits.

Such models keep money recirculating locally rather than extracting it. The estimate of the ‘multiplier’ from buying local is eight; this means that if you buy from a large multinational, that money leaves your community right away, but if you buy from a local business, it stays local and is spent on average a further eight times. Through such strategies—the opposite of neoliberal extraction—wealth can be kept recirculating, anchoring jobs and reversing long-term economic decline.

Today, the Evergreen companies are competing with the giant corporations that had previously provided contract services to the big anchors, even beating out the multinational firm Sodexo for the Cleveland Clinic’s full laundry contract. Evergreen has since acquired the former Sodexo plant, hired the former Sodexo workers, given them a pay raise to the local living wage, and put them on a fast track to employee ownership. No jobs were lost—all that has changed is that former corporate profits are instead recirculating back into Cleveland to the benefit of the local economy rather than leaking away to distant absentee shareholders.

Community Wealth Building has since spread far and wide. In the UK, Preston City Council in Lancashire has taken the approach and successfully implemented it at a city-wide scale with the help of the Manchester-based Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES). The ‘Preston Model’, as it has become known, encompasses a string of public anchors across Preston and Lancashire, to which has been added public pension investment and affordable housing, while laying the groundwork for a community bank.

Once a poster child for economic deprivation and ‘left behind’ places, Preston has already seen significant payoffs from its CWB approach, having been named the UK’s most improved urban area. The share of the public procurement budget spent in the city quadrupled between 2013 and 2018, a gain of £75m, while across Lancashire it more than doubled for a gain of £200m. Unemployment has fallen, and Preston has seen better-than-average improvements in health, transport, work-life balance, and youth and adult skills acquisition.

Other parts of the UK are now following this lead, from Salford and Wirral to North of Tyne, Newham, Islington, and North Ayrshire. The latter became Scotland’s first local government to adopt a CWB strategy, designed to support its net-zero carbon ambitions and a just transition. What once seemed like a fringe idea is moving fast towards the mainstream, a new way for local governments to shape their local economies. The Covid-19 pandemic and accompanying crisis makes these strategies all the more important.

Recent UK local elections show that such approaches also bear electoral dividends, with Preston and other Labour areas pursuing CWB strategies bucking the Conservative national tide. Meanwhile, Scotland’s SNP government will now be taking up a CWB Act, having just announced the first ever government minister for Community Wealth.

CWB is in the process of crossing the Irish sea. Few places have a more urgent need for such an approach than does Ireland, the extractive economy par excellence, where communities have been ravaged by neoliberalism and austerity.

The Irish economy has been based on low wages, precarious employment, financialised property speculation, and foreign direct investment, coupled with state subsidies and tax breaks for transnational capital. The North has adopted large parts of this model wholesale. The result is an agglomeration economy that has concentrated power and capital in the urban centres of Dublin and Belfast at the expense of state-led investment, indigenous enterprises, balanced regional development, and the needs of ordinary working people.

• Sinn Féin’s Minister for Communities Deirdre Hargey, has expressed strong support

There is already growing interest in CWB at the local level in Ireland — in Dublin, Belfast, Cork, and elsewhere. Trademark Belfast has taken up CWB, as has the Development Trust of Northern Ireland, while Sinn Féin’s Deirdre Hargey, Minister for Communities in the Northern Ireland Executive, has expressed strong support. The term Tógáil Maoine Pobail is to be submitted to the Irish Dictionary Committee for recognition as the official translation of “Community Wealth Building” in Irish.

A highly adaptable approach, CWB could be implemented virtually everywhere, from deindustrialised East Belfast to the decaying communities of Ireland’s western and border regions. As well as providing the basis for a new model of urban development, there are suggestions that CWB could be applied to promote regeneration, tackle inequality, and support transition in rural Ireland.

CWB presupposes new levels of community control and the expansion of community power. Ireland has a well-developed community infrastructure, a parallel state that has long supported working-class and marginalised communities when governments have not. These networks and traditions could now come into their own as part of a CWB approach to building a new economy in Ireland, one in which the needs of the community and planet are at long last placed before the prerogatives of private capital.

Joe Guinan is Vice President of The Democracy Collaborative and co-author, with Martin O’Neill, of The Case for Community Wealth Building (Polity, 2019).