16 August 2021

Roger Casement remembered in London

• Francie Molloy speaking outside Pentonville Prison to mark the 105th anniversary of the execution of Roger Casement

On Sunday 8th August, Irish republicans gathered outside Pentonville Prison in Islington, London, to mark the 105th Anniversary of the execution of Roger Casement. The only 1916 rebel leader to be executed outside of Ireland.

The commemoration was well attended, with around 70 people in total, and was addressed by Francie Molloy, MP for Mid Ulster. Attendees maintained social distancing and face masks were encouraged. It was organised and hosted by the Terence MacSwiney Commemoration Committee.

In his opening remarks, Francie Molloy acknowledged that it was the first time since the outbreak of the pandemic that such a gathering could take place safely and that he was glad to be back once more with the London-Irish community.

Casement and London

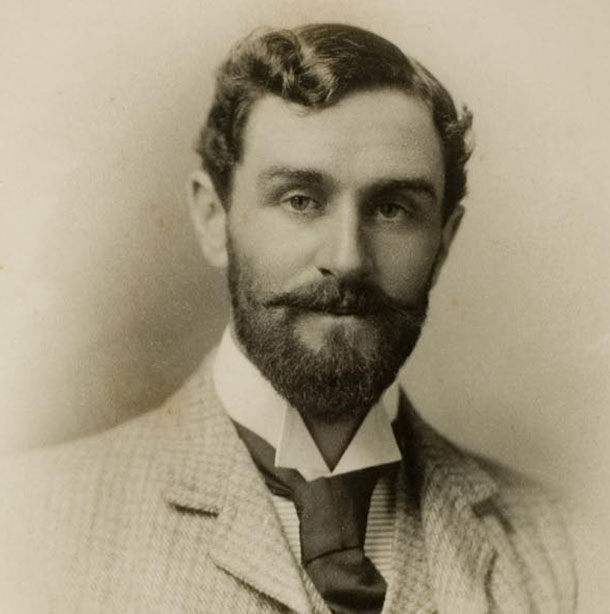

Roger Casement had a curious relationship with the city of London.

The ever-moving, almost nomadic, nature of his life meant that he was frequently resident in London. Often against his personal wishes. His preference was always to be home in Ireland or traversing the globe; rather than stuck in England’s capital. In November 1912, on his return from Peru, he wrote to his friend Mary Emmott: ‘I am stuck in London for the moment over official things – but I leave for Ireland on Saturday next I hope. This place is impossible – and I am impossible at present. I cannot see people at all – or talk civilly even – and am longing to be told by the FO [Foreign Office] that I am free to get away abroad altogether.’

Part of his childhood had been spent living in London and he received his early primary education there. Before relocating back to Ireland and completing his schooling at the Diocesan School in Ballymena, Co. Antrim (now the Ballymena Academy).

In later life he lodged at No. 50 Ebury Street, in Pimlico, London. This was where his diaries and papers were discovered following his capture. Diaries that would later occupy a disputed place in Ireland’s history.

Casement was a known personality in London. He well-regarded for his 1904 Report into the human rights abuses on the rubber plantations of the Congo Free State; a privately owned statelet ruled-over by King Leopold II of Belgium. And later again, in 1910, for his service on a Commission investigating the British-registered Peruvian Amazon Company’s enslavement and torture of Putumayo Indians.

However, as vociferously as he opposed imperialism and colonialism in the Congo, Peru, and elsewhere; his thoughts increasingly returned to injustices back home in Ireland. As he later remarked himself, “when up in those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold I also found myself – the incorrigible Irishman.”

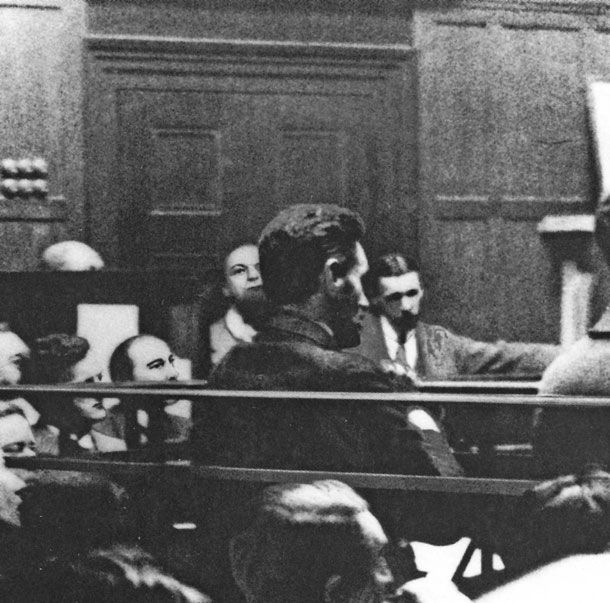

• Roger Casement (back to camera) in the dock

Anti-colonial politics in the heart of the British Empire

The close of the nineteenth century saw a vibrant nationalist revival within Ireland’s intellectual and cultural sphere. Roger Casement was closely associated with this new wave of thought. Fast becoming a known character within the Irish language and literary scene; but also, increasingly within separatist and republican circles.

In London, he worked closely with the essayist Robert Lynd to arrange events and provide support for Gaelic League sympathisers in England. Alongside this language activism, London was also the setting for some of Casement’s first forays into direct political activism and organising.

On 10 December 1903, in Chester Square, Belgravia, Casement first met the journalist E.D. Morel. It was a meeting of minds that Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, would later herald as ‘the most dramatic scene in modern history.’

The two men immediately struck up a close friendship, built around in their shared concern for the plight of the Congolese people. The following month, on 4 January 1904, in the coffee room of the Slieve Donard Hotel, Co. Down, the pair agreed to establish the Congo Reform Association.

The Congo Reform Association would go on to become one of the most successful pressure groups in early twentieth century British politics. It provided a model for broad-based organising and mobilisation in support of universal human rights and international solidarity. The movement successfully unified various stands of liberal, socialist, and progressive thought in Britain on a single platform. As Angus Mitchell observes, ‘in any inclusive study of the roots of modern British socialism and internationalism, Casement’s collaboration with E.D. Morel should be cited as a critical conjuncture in a tradition of English radicalism and the struggle for the fairer distribution of land.’

On 7 June 1905, Roger Casement personally organised a high-profile Holborn Town Hall meeting, in central London, where multiple public figures publicly adopted the ‘Belgian Solution’. Although, due to his position as a public servant, his role remained behind the scenes. The ‘Belgian solution’ had been developed by Casement and Morel with the assistance of the Belgian socialist and fierce critic of Leopold II; Emile Vandervelde. Under the terms of the solution responsibility for the Congo would be transferred out of Leopold II’s hands and instead vested to the Belgian Government. This ‘Belgian Solution’ proved a success and was subsequently adopted by the British Government and ultimately, with considerable reluctance, by Leopold II. Marking a first, albeit tentative, step in the dismantlement of Belgian rule in the Congo.

Casement firmly saw such activism as part of a wider internationalist effort against imperialism. As he confided to Morel, ‘Tackling Leopold in Africa has set in motion a big movement – it must be a movement of human liberation all the world over.’

• Robert Monteith with Roger Casement and Daniel Bailey on a German U-boat on their way to Ireland, April 1916

Gun-running and revolution in Ireland

London also provided the setting for another momentous occasion in Casement’s political life. As his opposition to British interference in Ireland intensified, Casement became further convinced of the need for arms in the hands of Irish nationalists.

On 8 May 1914, at No. 36 Grosvenor Road, Westminster - the home of his closest friend Alice Stopford Green - Casement met with Eoin MacNeill, Darrell Figgis, Erskine Childers, and Alice Stopford Green to discuss the proposal of importing arms. Darrell Figgis left behind a vivid description of the scene:

‘It was a grey afternoon. The windows gave on to the Thames, and against the grey sky the warehouses on the southern bank were, through the gathering mist, lined in an outline of darker grey and black, the tall chimneys uplifted above them. The tide was out, and beside the distant quayside some coal-barges lay tilted on the sleek mud of the river-bottom, with their sides washed by the silver waters that raced seaward. Against this picture, looking outward before the window curtains, stood Roger Casement, a figure of perplexity, and the apparent dejection which he always wore so proud, as though he had assumed the sorrows of the world.’

This meeting marked the genesis of the Howth and Kilcoole gun-landings of July 1914, a turning point that set in motion the momentum towards the Easter Rising.

• Joe Dwyer at Roger Casement commemoration

Capture and Execution

Of course, London also served as the site of the final chapter of Casement’s life.

In the early hours of 21 April 1916, Casement famously landed on the Banna Strand, Co. Kerry. Alone and without radio, he was soon captured by the RIC at McKenna’s Fort, Ardfort.

Ironically, two of the men who supposed to contact the Aud and collect him that morning were former Gaelic League London members; Dónal Sheehan and Con Keating. Themselves the products of the Irish language revival scene in London that Casement had enthusiastically encouraged and supported while living there. Sheehan and Keating tragically did not make it to Casement due to a motor accident at Ballykissane, Co. Kerry, in which they drowned alongside their comrade Charlie Monahan.

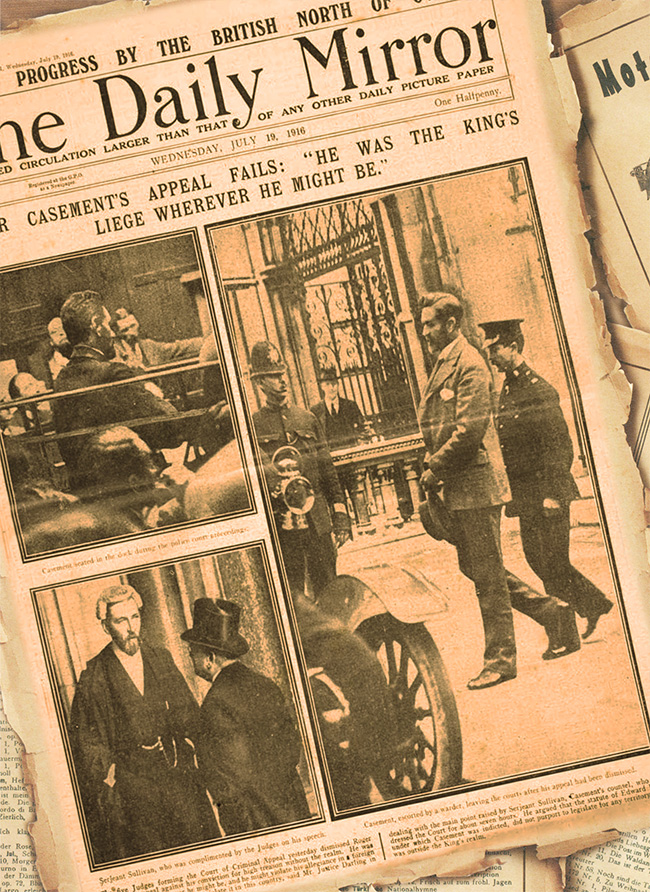

Casement was arrested and brought to London early in the morning of Easter Sunday, 23 April 1916. The following day the Easter Rising was launched. During his time in London, he was held in the Tower of London, Brixton Prison, and ultimately Pentonville Prison.

At a special meeting of the Gaelic League London Ard-Choiste, on 20 July 1916, a motion was passed voicing opposition to newspaper reports that there was any popular sentiment in Ireland supporting his execution. The League soon embarked on a London-wide collection of signatures pleading for clemency.

But while Casement was once again in London, his thoughts were as ever on home. As his cousin Gertrude later described, during his court appearance:

‘Roger looked wonderfully tall and dignified and noble as he stood in the dock. He seemed to be looking away over the heads of the judges and advocates and sightseers, away to Ireland – probably his mind’s eye was fixed on some well-known spot such as Fair Head or Murlough Bay – certainly he had no look of one who was conscious of his awful and sordid surroundings…’

Casement was ultimately hanged for alleged ‘treason’ on 3 August 1916. His executioner later remarked that he was ‘the bravest man it fell to my unhappy lot to execute.’

Legacy

In death his association with London was firmly cemented. Despite his request to be buried in Murlough Bay, Co. Antrim, he was buried in a ‘traitor’s grave’ behind the prison walls of Pentonville Prison.

In 1917, when the London Sinn Féin club was reformed at Chandos Hall, just off the Strand, it adopted the title ‘the Sir Roger Casement Sinn Féin Club’ to his memory.

The repatriation of Casement’s body to Ireland became a longstanding campaign and rallying point for the London-Irish community over the successive decades. It was finally secured in 1965, although, due to partition, he was reinterned in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, rather than his final wish of Murlough Bay.

Casement’s legacy is an important one for the Irish people globally. Arguably no other Irish republican championed the cause of internationalism as ably as he did. He placed the cause of Ireland on the world stage. Tying Irish freedom with the freedom of all small nations and struggling people.

This internationalism was not additional to his republicanism. It was central to it. As he said himself, ‘the more we love our land and wish to help her people the more keenly we feel we cannot turn a deaf ear to suffering and injustice in any part of the world.’

It is a message and a legacy that needs to be heard today. Especially amid the current global health pandemic and climate crisis.

As Francie Molloy MP observed in his address on Sunday:

‘Casement’s belief in solidarity and cooperation between all the people of the world is fundamentally republican. It is a principle that is often ignored or diminished by the opponents and detractors of Irish republicanism. We’re not ‘Little Irelanders’. Our vision is fundamentally internationalist. We stand with struggling people of the world – and we are confident in the fact that they stand with Ireland too. In our own day and age – we reiterate our call for a global response to the current health pandemic. A global pandemic requires a global remedy. We face an enormous responsibility. No-one is safe until everyone is safe. No-one is free until we’re all equal. That is where Casement would have stood.’

The author wishes to thank Frank Glynn and Felix Maguire of the Terence MacSwiney Commemoration Committee for all their work organising Sunday’s commemoration. And also, Emmett for recording the commemoration and Louisa for allowing the use of her photographs.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures