18 February 2021 Edition

Republicanism and ecology politics

Seán Fearon challenges republicans to consider incorporating a green agenda into their political activism ‘When we think of economic performance as Irish republicans, we must prioritise social and economic equality, redistribution, physical and mental wellbeing, the quality of employment, the impact on our democracy, the health of our communities, and the sanctity of the natural world’.

Irish republicanism, as the primary vehicle of radical social and economic progress on this island, is perhaps an outlier among mainstream left-wing movements in continental Europe, Britain, and the United States. Environmentalism and an embrace of green politics is, at best, tangential to our programme of change on this island.

Misconceptions may lie in the widely held view that the politics of ecology - the balance between the ecosystem of humanity, our economic activity, and all other ecosystems on earth - are some sort of middle-class hobbyhorse. It is perhaps for this reason that the climate emergency is on the coat-tails of our economic programme; a sort of appendix to the social justice arguments that have made Irish republicans relevant in exploited communities, now as ever.

However, the anti-colonial, anti-imperialist and often socialist forms in which Irish republicanism has found expression since the 1790s are bonded to the politics of ecology. The British imperial project in Ireland, and its colonial practices of land confiscation and exploitation of Irish workers which have animated republicans throughout our history, are the same practices which have brought us to the brink of ecological collapse. They are bound together by the logic and pseudo-religious obsession with economic growth.

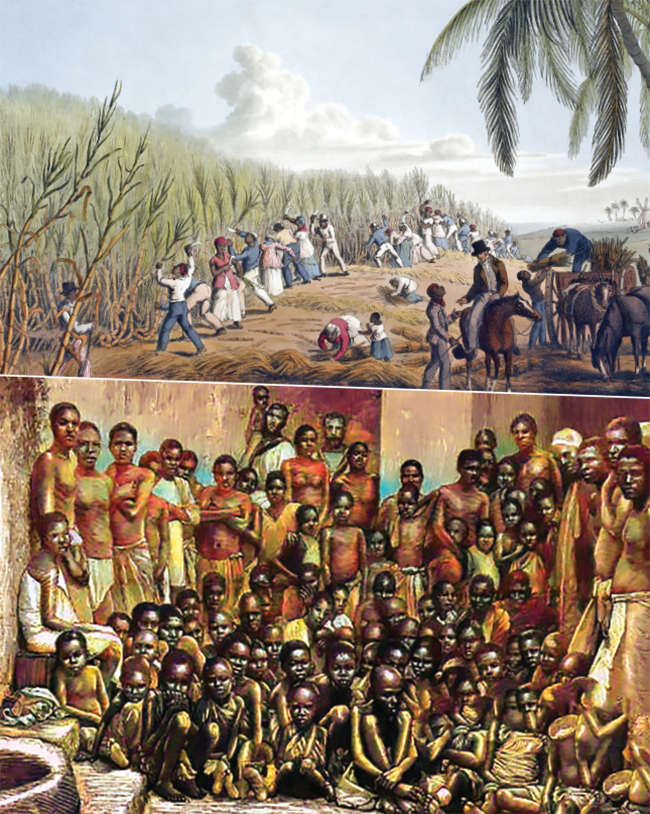

Like the people of East Asia, the continent of Africa, and Latin America, generations of working people in Ireland were exploited and brutalised at the altar of imperialist growth, but among post-colonial societies, the Irish state stands out as uniquely growth-obsessed. We have swallowed whole the myth that rising national output and a bejewelled arrangement for multinational corporations is one and the same with economic development and a modern, humane and ecologically sustainable society.

Generations of working people in Ireland, like the people of East Asia, the continent of Africa, and Latin America, were exploited and brutalised at the altar of imperialist growth

Of course, Ireland is not alone in this. There is a blinkered obsession among policy makers, political parties from right to left, and, above all, the economics profession with growth as the sole measure and object of economic performance. It dominates today’s globalised capitalist economy. Everything else is secondary, namely the well-being of society, the health of our communities, and the disfigured state of the natural world.

‘Growthism’ is an idea entirely at odds with indigenous concepts of progress and wellbeing, in Ireland as in other colonised regions. In our aim to unravel the malicious legacy of colonialism here, and the layered economic inequality it left in its wake, republicans should share common cause with those rejecting endless economic expansion to bring the world economy back into line with our planetary boundaries.

In short, we need a ‘greening’ of Irish republicanism and a vision of a new model of a post-growth economy in Ireland.

Imperialism & economic growth

The pages of An Phoblacht will be very familiar with interesting and much more detailed accounts of the history of Britain’s colonial subjugation of Ireland than I am able to muster.

However, it should be known that the arrival of Oliver Cromwell to Ireland in the mid-17th century marked not just the violent confiscation of vast swathes of land, but the plantation of new theories about the purpose of economic activity – growth.

By Cromwell’s side was a man called William Petty, credited in some quarters as the progenitor of developed ideas of political economy and economic growth. In order to make a success of the plantation and colonisation of Ireland, Petty argued, the Irish people would need to be Anglicised, made more productive, their population expanded, and driven to economic growth.

It is no coincidence that, as Petty scribbled his racialised theories of progress, the foundations of modern capitalism were being laid in Britain through the ‘enclosure’ movement. This involved the first privatisation of common lands which fundamentally altered the relationship between rural peasantry and their ruling class. Instead of living on and working the land for subsistence, they now lived on privately-owned land which required them to pay rent. They would also need a wage to pay this rent and buy the food they once gathered from the land. A rural class of wage-labourers was born.

The economics of growth, of boom and bust, have failed

In the simplest possible terms, economic growth is the practice of economic activity producing more value in its outputs than it consumes as inputs. We constantly think of outputs, goods and services which create rents, profits, and dividends for their owners. We rarely think of the inputs, namely people and their labour, raw materials harvested from the earth, and energy.

Growth is the product of the competitive and expansionary engine of capitalism and, as the British Empire moved beyond Ireland, it and its imperial competitors scoured the corners of the earth for slaves, fossil fuels, and valuable goods to trade. The size of the world economy expanded rapidly.

The same impulse for ever greater and faster economic expansion underpinned the industrial revolution and would create rates of economic growth we are familiar with today. Due to compound function of growth, any economy that grows by three percent a year, every year, doubles in size every twenty-five years or so.

The implications of this for the natural world and our climate are now terrifyingly clear. As a result of this model of growth, we are in the midst of the sixth great extinction event in world history and runaway global heating now threatens human civilisation as we know it.

Ireland’s post-colonial economy

Despite this, growth is now the order of the day, and, for most, it is synonymous with sound economic management, regardless of what is growing or how much of that growth is creamed off by a privileged few. However, for post-colonial societies around the world, a very specific model of growth exists.

Political economists argue that, for much of its history, the Irish state might be usefully viewed as a rich developing nation, and not a poorer developed nation. In other words, we are Newly Industrialised Country (NIC), akin to our post-colonial counterparts in east Asia and Latin America, for three reasons.

Firstly, we did not industrialise in the 19th century, instead a socially-engineered famine devastated our economic capacity.

Secondly, post-Partition Ireland was left unable to partake in the post-war 20th century class compromises that produced universal public services, stable indigenous export-led development and an unprecedented rise in living standards achieved across the rest of Europe and the United States. Instead, to paraphrase Peadar Kirby, gombeen governments ‘rode the agricultural donkey as Europe galloped ahead on the industrial stallion’.

Thirdly, when Fianna Fáil embraced globalisation and a new Irish neoliberalism with its 1958 Programme, it sowed the seeds of the ‘dual economy’ seen in post-colonial societies across the world – a booming multinational sector dependent on foreign investment and another entirely separate, much less profitable ‘real’ economy rooted in our towns and villages.

Moreover, these two economies have diverged further and further at each major economic event in our recent history – the Celtic Tiger, the 2008 crash, and now the ‘COVID crash’.

The profitability of, typically American, multinationals involved in the trade of high-tech services in Ireland is well-documented. Meanwhile, outside of these FDI enclaves in the urban hubs of the Irish state, market income inequality is the highest in Europe and the worst in the OECD, half a million homes don’t have access to elemental utilities such as broadband and poverty is pervasive.

Embracing post-growth Irish republicanism

The point here is that economic growth as the sole objective of economic success is not only breaking down the fragile limits of our planetary system, but the post-colonial nature of the Irish growth model is glaringly unequal, leading to regional imbalances and underdevelopment, and has created an almost neo-colonial dependence on foreign investment to fund basic public services.

And while growth as a primary objective may have been defensible when countless Irish people lived in abject deprivation, we are now an advanced society with more than enough resources to satisfy the needs of every citizen plentifully.

Katherine Trebeck writes that in advanced societies like ours, with loneliness, mental ill-health and deep dissatisfaction in work spreading like wildfire, the fruits of past growth are now rotting before any of us can enjoy them.

This is because growth, and the ever greater strain demanded of us to satisfy it, is simply not a measure of development in and of itself. Improving metrics of global income like GDP or GNI were never designed to objectives of progress in and of themselves.

Since 1980, a staggering 48% of growth in global income has gone to the richest 5% in rents, interest on loans, profits, and dividends through the assets they have accumulated. Workers don’t, and increasingly won’t, see the benefits of growth.

We need new humane and modern objectives for development which break from our colonial and post-colonial relationships with ‘growth at all costs’. Growth should be superfluous, an accident, and, for a time, it was necessary. However, for the sake of planetary stability and a fairer society on this island, it can no longer be the primary objective of economic policy.

Seán Fearon is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University Belfast researching post-growth political economy and a green response to COVID-19