26 May 2021

Fullerton family’s 30 year campaign for justice

• John Joe McGirl, Katie Keaney & Mary Ann Fallon (nieces of Seán Mac Diarmada) and Eddie Fullerton, at Seán Mac Diarmada commemoration, kiltyclogher, Co. Leitrim

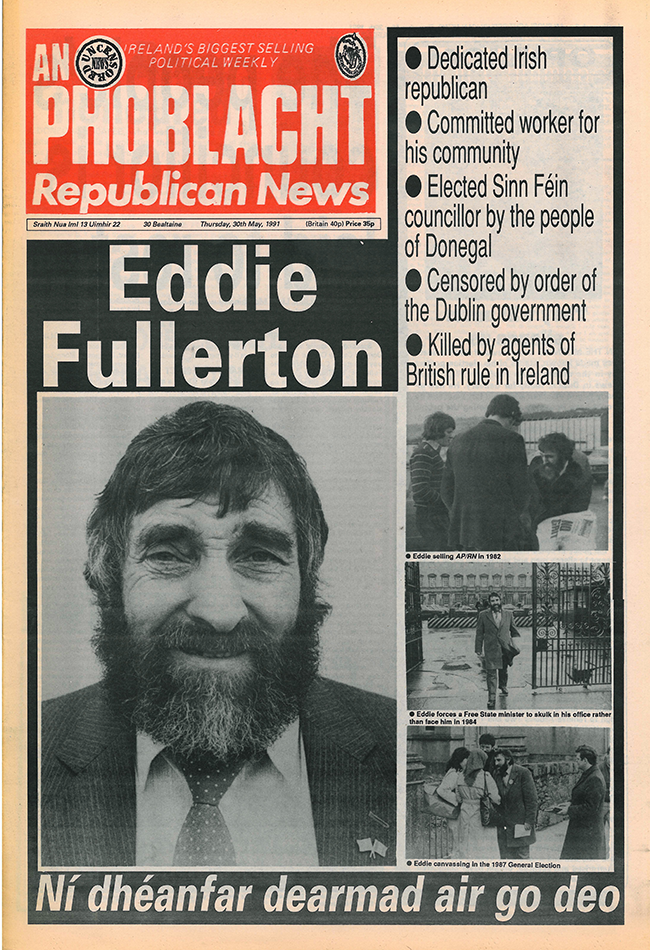

May 25th marked the 30th anniversary of the assassination of Sinn Féin councillor Eddie Fullerton. Roy Greenslade catalogues the Fullerton family’s ongoing campaign for justice. First published in An Phoblacht Issue 1 - 2021

Justice, to paraphrase William Butler Yeats, comes dropping slow. And especially slow for republicans. All too often, it does not come at all. That, sadly, has been the reality for the family of Eddie Fullerton, a Sinn Féin councillor in Donegal shot dead by a UDA gang 30 years ago.

Now, his family are marking the anniversary of his death by going on the offensive. Eddie’s 81-year-old widow has instigated a legal action against the British state to hold its officials and its police force to account for colluding in his murder.

It was in May 1991 when Eddie was gunned down inside his home. He was, by all accounts, a special man. Born on a small farm in Buncrana in March 1935, he was the eldest of 20 children born to John and Mary Fullerton. He was unable to continue his schooling beyond the aged 12, despite winning plaudits from his teachers, because his father needed him to work on the farm.

Aged 18, he went to Scotland to find work, eventually moving south to Birmingham. There, he fell in love with Diana Peach, started a construction business (employing many men from Donegal), raised a family of six, and became intensely interested in Irish politics.

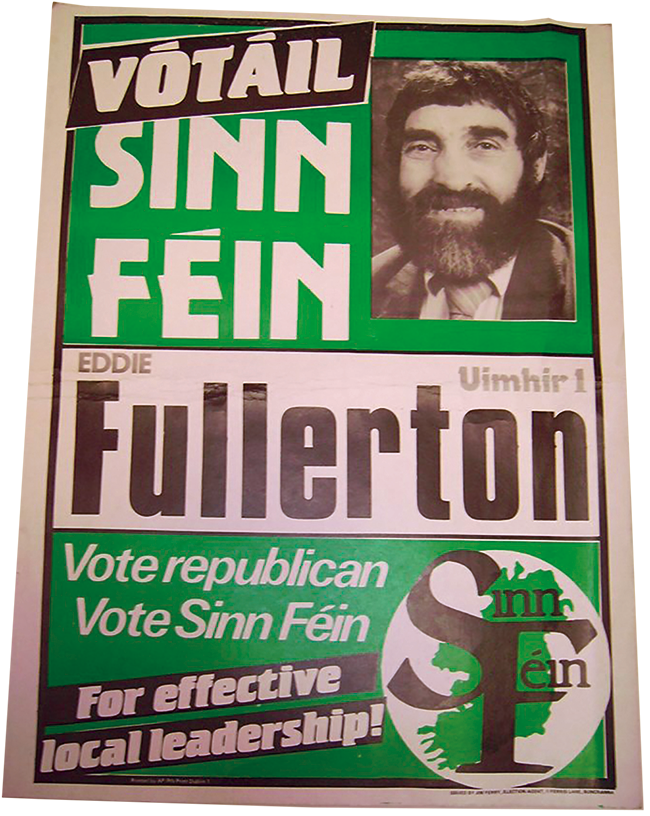

By the time he returned to Buncrana in 1975, he was a committed republican. Four years later, Eddie became the first Sinn Féin member in the modern era to be elected to Donegal County Council, where he topped the poll. Two of his comrades, the party’s former Vice President, Pat Doherty, and Liam McElhinney, both described him as “a larger-than-life character.”

They spoke of his hard work on behalf of the people of Donegal and the efforts he made to promote the party. According to Gerry Adams, he was renowned for being the largest seller of An Phoblacht by touring Inishowen every weekend, visiting scores of pubs and standing outside masses in Buncrana, Clonmany, and Carndonagh. “He was a pioneer, a driving force,” said Doherty. “He was outspoken, dedicated, and a relentless campaigner with a talent for organisation.”

There is an enduring memorial to his most successful campaign over the course of 12 years; the construction of a dam in order to create a reservoir above Buncrana. Completed six years after his death, it is now known officially as the Eddie Fullerton Dam and immortalised in a poem by Martin McGuinness.

Eddie was imbued with a socialist spirit. “He stood up for the underdog,” says McElhinney. “He was tenacious, wanting people to have their due rights. He took up people’s concerns and pursued them with vigour. It didn’t matter whether they supported the party or not. If he felt they needed help, he got stuck in on their behalf.”

Both Doherty and McElhinney were with him the night he was murdered. After Eddie had spent the earlier part of the evening at the opening of a sewerage plant in Buncrana by the then Environment Minister, Pádraig Flynn, he joined Pat and Liam at an election meeting in Letterkenny.

It was late by the time it ended and Eddie dropped Liam at his home before driving to Buncrana where Diana was waiting up. She made him tea and sandwiches, and it was after 1am before they went to bed.

About an hour later, they were woken by a loud bang – the front door had been sledge-hammered open – and heard shouting. Eddie quickly slipped on his trousers and went to investigate. He was confronted on the landing by two armed men. Rising from her bed, Diana heard a volley of shots, and then two more. As the killers fled, she found his body slumped across the floor, blood streaming from his head. She knew immediately that her 56-year-old husband was dead.

The massive turn-out at his funeral spoke volumes about his popularity and the grief of the community he served. but the meticulously planned assassination of Eddie – which was claimed by the UFF, a cover name employed by the UDA – also spoke volumes about the nature of the UDA’s activities. It was blindingly obvious that the attack could not have happened without British and Irish security force assistance.

The questions thrown up by the attack all pointed to collusion. How did they know where Eddie, who had received a loyalist death threat the year before, lived? Who provided them with the intelligence? What gave the gang the confidence to carry out an attack so far from the Border? How could they be sure of making their escape? What role was played by the Garda Síochána?

At the time, policing on the Border was well established with superintendents on each side meeting regularly to review intelligence. It was heavily fortified. No car could cross to and from the Six Counties without going through a checkpoint staffed by either the British Army or RUC officers. Yet, there is clear evidence that the killers were able to pass into Donegal from Derry and back again undeterred.

Once they reached Buncrana, their first act was to take a local family hostage. They must have had local knowledge to be directed to that house, from which they took the family’s car and a sledge hammer.

As for their escape, a witness approached the RUC the day after the murder to say he had seen three men wearing army fatigue-style clothing on the beach at Culmore Point. It was 2.30am, about half an hour after the shooting. He saw a Ford Sierra arrive, pick up the men and drive towards the Culmore checkpoint just two miles away. As a TV cameraman who regularly covered the Troubles, he recognised it as an unmarked RUC car. Significantly, the gang’s burned-out getaway car was found beside the beach the following day.

The witness covered the aftermath of the attack on Eddie and, on returning home, he told some RUC men what he had seen. Later, he was visited by a plainclothes officer who insisted he must speak to an RUC superintendent waiting in a car outside. When he got it in, he found there was a Garda Síochána superintendent inside as well.

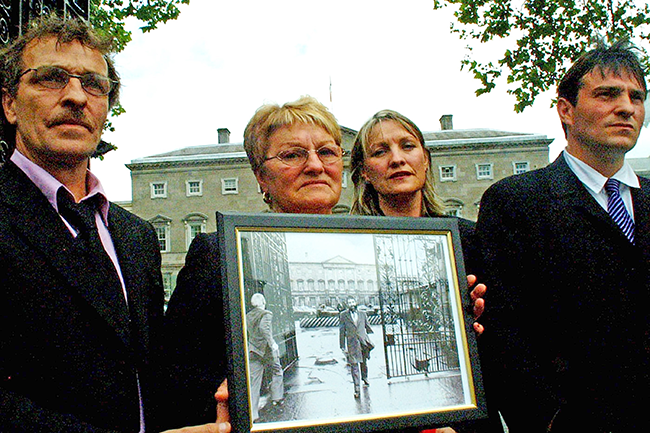

Fullerton Family - Albert (son), Dinah (wife), Amanda (daughter) and Eddie Jnr (son) outside Leinster House, carrying a 1984 photo of Eddie leaving Leinster House after a Labour Minister objected to his presence on a council delegation from Donegal

Both men were concerned to know whether he could identify the men he saw. He noted that the officers were tense until he said he couldn’t do so. Then, they relaxed. No notes were taken during this most unorthodox of interviews. The witness was told he would be contacted, but heard nothing. He was never contacted by either RUC or Gardaí to make a statement.

His sensational evidence finally came to light in 2003 after he was approached by one of Eddie’s sons, Albert. To date, that witness, in spite of attempts by both police forces to discredit him, has provided some nine formal statements to a range of investigators, all of which have been consistent. The Police Ombudsman in the North regarded him to be “a significant witness who had witnessed an indictable and triable offence”. The ombudsman also identified an RUC officer who remembered the witness coming forward on the day of the murder to inform senior RUC officers what he had seen the previous night.

Two other key pieces of evidence emerged much sooner after Eddie’s murder. A month later, a British TV current affairs programme, ‘World In Action’, revealed that an RUC file containing Eddie’s photograph and his details had been found in the possession of the UDA in Derry. In the same file were the details of another Sinn Féin councillor, John Davey, who had been shot dead in February 1989. Then, in April 1993, the weapon used to murder Eddie was recovered following the killing of four men at Castlerock, north Derry, the month before.

By normal standards, these revelations should have been more than enough to warrant an official inquiry. In its absence, Eddie’s family, led by Albert, formed the Eddie Fullerton Justice Committee in 2004 in order to unveil the truth about the assassination, collusion and cover-up. (Tragically, Albert was killed in a road accident in 2006).

Meanwhile, against the background of links between Eddie’s killing and that of other victims of loyalist attacks in the 1988-94 period, the Police Ombudsman in the North has conducted an investigation, known as Operation Greenwich. Its findings are expected to be released later this year.

Whatever the outcome, the family are determined to pursue legal action against the British state, on the grounds that it is ultimately responsible for Eddie’s murder, whether by commission or neglect.

Eddie’s daughter, Amanda, said: “For 30 years, our family has suffered blatant injustice. The police authorities and their agents on both sides of the Border have consistently demonstrated a gross dereliction of duty and an abuse of power, as is evidenced by the flawed investigation that followed my father’s murder.

“Those government officials who chose to turn a blind eye to this glaring injustice are also to blame. My father was not just a beloved family man, he was also loved by the community he represented. We all deserve to know the truth about the conspiracy to have this ‘beautiful man of the people’ assassinated.”

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures