22 May 2021

The Partition Election, 'Northern Ireland' and the Second Dáil

Remembering the Past - 100 years ago

• Ulster Special Constabulary in Belfast

100 years ago this week the election to the new ‘Northern Ireland’ Parliament marked the beginning of the Orange state

In May 1921 the war in Ireland was continuing with ever greater intensity as the British government deployed its military forces against the civilian population in a vain attempt to defeat the IRA. There were military trials and death sentences, ‘official reprisals’ that saw homes and businesses burned out by British forces, and daily deaths in the conflict. At the same time the British government was advancing its plan to impose Partition under the Government of Ireland Act and it was soon to use negotiation as well as coercion to achieve and consolidate this outcome.

Theprinciple of Partition had been introduced by British Prime Minister Asquithinthe House of Commonsin March 1914when heproposed “county option with a time limit” by which any of the nine counties of Ulster might vote out of Home Rule for a period of six years. In May 1916, a few days after the last Easter Rising executions in Kilmainham Jail, Lloyd George, soon to be British Prime Minister, wrote secretly to Unionist leader Edward Carson on the proposed ‘provisional period’ of exclusion of Ulster from Home Rule: “We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland.”

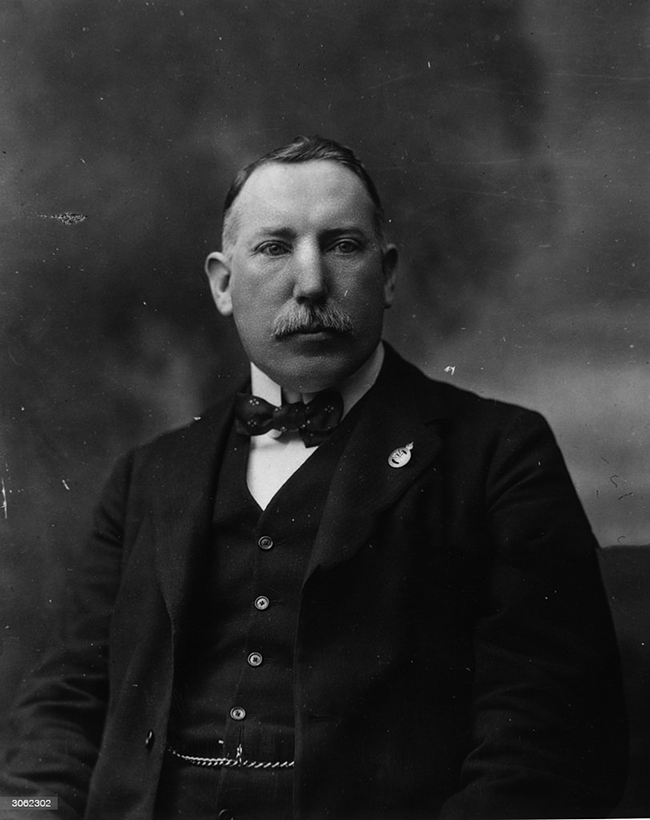

Unionist leader Edward Carson

Then and subsequently British and Irish Unionists politicians said repeatedly that they would not stand for the “coercion of Ulster”, meaning the inclusion of ‘Ulster’ (however they chose to define it geographically) in Home Rule for Ireland. In reality the coercion that actually existed took two forms:

- The attempted violent suppression of Sinn Féin across most of Ireland by the British government, despite the overwhelming mandate for Irish independence it received in the December 1918 election. This coercion escalated with the armed resistance of the IRA, developing into guerrilla war in late 1919, and terrorist repression led by the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries in 1920 and ’21.

- The sectarian and political pogrom in the North-East against Catholics, nationalists, republicans and any, including trade unionists in Belfast, who opposed Partition. Beginning in July 1920 Unionist mobs, including armed Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) members, expelled an estimated 10,000 workers from their jobs and drove hundreds of Catholics from their homes and businesses. Between July 1920 and July 1922 nearly 500 people were killed in Belfast alone. 60% of the dead were Catholics, though they made up just 30% of the population.

The British government appointed leading Tory Unionist Walter Long to devise a legislative scheme to provide for both Partition and some form of Home Rule. In November 1919 his committee reported to the British Cabinet that they must “oppose any solution which would break up the unity of the Empire” and exclude any proposal “for allowing Ireland or any part of Ireland to establish an independent republic”. The report said “Ulster must not be forced under the rule of an Irish Parliament against its will” and no attempt must be made to establish “a single parliament for all Ireland”.

But what was ‘Ulster’? Was it the historic province of nine counties? Since the first Home Rule Bill in 1886 Unionists had presented nine-county Ulster as the bulwark against Home Rule. During the constitutional crisis of 1912-14 the British Tory Party had united with the Unionists in Ulster to threaten armed revolt against the British Liberal government if it introduced Home Rule and when war broke out in 1914 Home Rule was suspended. Unionists looked forward to the exclusion of the nine counties if Home Rule was revived after the war but the overwhelming victory of Sinn Féin in the 1918 General Election and the 1920 local elections gave them a wake-up call. Unionist domination could not be guaranteed in a too finely electorally balanced nine-county Ulster.

In February 1920 Walter Long wrote to the British Cabinet that the people in inner Unionist circles “hold the view that the new province should consist of the six counties, the idea being that Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan would provide such an access of strength to the Roman Catholic party that the supremacy of the Unionists would be seriously threatened”. This was stated more explicitly by Unionist leader Edward Carson in Westminster in May 1920: “We should like to have the very largest area possible, naturally. That is a system of land grabbing that prevails in all countries for widening the jurisdiction of the various governments that are set up; but there is no use in undertaking a government which we know would be a failure if we were saddled with these three counties.”

Of course the six counties of Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone, were not by any means uniformly Unionist and within that area there was an anti-Unionist, anti-Partition minority of around 35%, the latter forming a majority in Counties Fermanagh and Tyrone and in the towns of Derry and Newry. Therefore it was necessary to terrorise the minority into submission if the new Partition set-up was to succeed. Visiting Belfast in July 1920 Carson used rhetoric that stirred up the pogrom. His fellow leader James Craig did likewise and successfully pressed the British government to establish the Ulster Special Constabulary – the UVF with British money, guns and uniforms – in November 1920.

James Craig

Thus the scene was set for the Government of Ireland Act which became law in December 1920. Its real purpose was Partition and the establishment of the Parliament of ‘Northern Ireland’ as the six separated counties were to be known. For British domestic and international opinion the Act was sugar-coated with a ‘Parliament of Southern Ireland’, like its Northern counterpart under the British crown, in the Empire and dealing with purely domestic matters. For added sweetness there was a Council of Ireland with representatives from the two parliaments which could decide to unite, under the crown, if they wished. Of course the British knew that Sinn Féin would never sit in the 'Southern Parliament' but the implementation of the Act proceeded, with a steady eye on its main purpose of Partition and retaining British Empire control in Ireland.

The Act came fully into force on 3 May 1921 and 13 May was set for nominations for separate elections to the two Parliaments which were to be held on 19 May in the 26 Counties and 24 May in the Six Counties. The Sinn Féin leadership decided to contest the elections and regard them as elections for the Second Dáil Éireann, with all those elected in the 32 Counties entitled to take their seats in the new Dáil. When nominations closed in the 26 Counties there were only Sinn Féin candidates nominated and they were deemed elected. Both the old Nationalist Party led by John Dillon and the labour movement had decided not to contest, leaving the field open for Sinn Féin to demonstrate clear national opposition to Partition.

Rural patrol by Specials

In the Six Counties the elections were fiercely contested and there was widespread intimidation of nationalist voters. The ‘Irish News’ pointed out that Catholics in East, North and South Belfast “are to be asked to return to the streets out of which they fled for their lives last July to mark their ballot papers”. On 17 May thousands of loyalist shipyard workers mobilised and successfully prevented an Independent Labour meeting from taking place in the Ulster Hall, because the candidates were pledged to “an unpartitioned Ireland based on the goodwill of all who love their native land”. Two days later over 250 Catholic workers, mostly women, were prevented from attending their work at Gallagher's tobacco factory in Belfast. In Fermanagh and Tyrone the newly formed Special Constabulary harassed Sinn Féin and Nationalist Party election workers and voters.

Polling day 24 May saw more intimidation, with the ‘Manchester Guardian’ reporting that “Unionists assembled outside the voting booths and set upon Catholic voters”, many of whom were injured, and “Anti-Partition personation agents were thrown out of several of the polling booths because they objected to the Unionist agents helping electors to vote. This left the Unionists free to personate all the voters who had not voted.”

Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party had agreed an election pact with votes being transferred in the PR system which was being used for the first time in a parliamentary election. Of the 52 seats in the new ‘Northern Ireland’ Parliament Unionists won 40, Sinn Féin won six and the Nationalist Party won six.

In the 26 Counties 124 Sinn Féin candidates were elected unopposed, as well as four Unionists. On a 32-County basis Sinn Féin again had a sweeping victory, winning 130 out of 180 parliamentary seats.

As Lloyd George frankly admitted, the majority in Ireland had again made clear their support for complete independence and the Irish Republic. But he and his government were not about to recognise that democratic mandate. The Six-County bulwark of the Empire had been established. Winston Churchill later wrote that once ‘Northern Ireland’ became a separate entity “clothed with constitutional form, possessing all the organs of government and administration…from that moment the position of Ulster became unassailable…Every argument of self-determination ranged itself henceforward upon their side. Never again could any British Party contemplate putting pressure upon them to part with the Constitution they had reluctantly accepted.”

Lloyd George and Winston Churchill

The newly elected Second Dáil Éireann was still forced underground, banned by the British regime, as was Sinn Féin, with many TDs in prison or on the run. In contrast the 'Northern Ireland' Parliament met for the first time on 7 June, but even with a large Unionist majority, and Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party abstaining, the Unionists MPs were not fully satisfied. Unionist MP William Grant said they would “takes steps to expel Sinn Féin from the Six Counties”. The day after the inaugural meeting of the Parliament renewed attacks on Catholics took place. At Carrogs, County Down, two Catholic men were murdered in their home by the Special Constabulary. During the rest of June there were killings of six Catholics in Belfast by the Specials, a number of Catholics and Protestants were killed during rioting and some 150 Catholics were driven from their homes.

Pogrom had prepared the ground for the setting up of the ‘Northern Ireland’ Parliament, pogrom greeted its establishment and pogrom would continue sporadically throughout its existence. Republicans and nationalists in the Six Counties could hardly believe that they would be abandoned to this. Most Republicans believed that Partition and the new Orange state could not last. Writing nearly 50 years later veteran Republican Máire Comerford summed up the feeling in the weeks before the July 1921 Truce and the start of negotiations with the British:

“We laughed hard at the thought that the English could make a lasting partition of Ireland against the practically unanimous will of the Irish people. Alas we had no conception either of their great ability, or the depths to which they would descend when the Conference stage was reached, their smile and their handshake more deadly than war.”

First meeting of ‘Northern Ireland’ Parliament in Belfast City Hall, 7 June 1921

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures