19 May 2021

McCreesh and O’Hara die on the same day

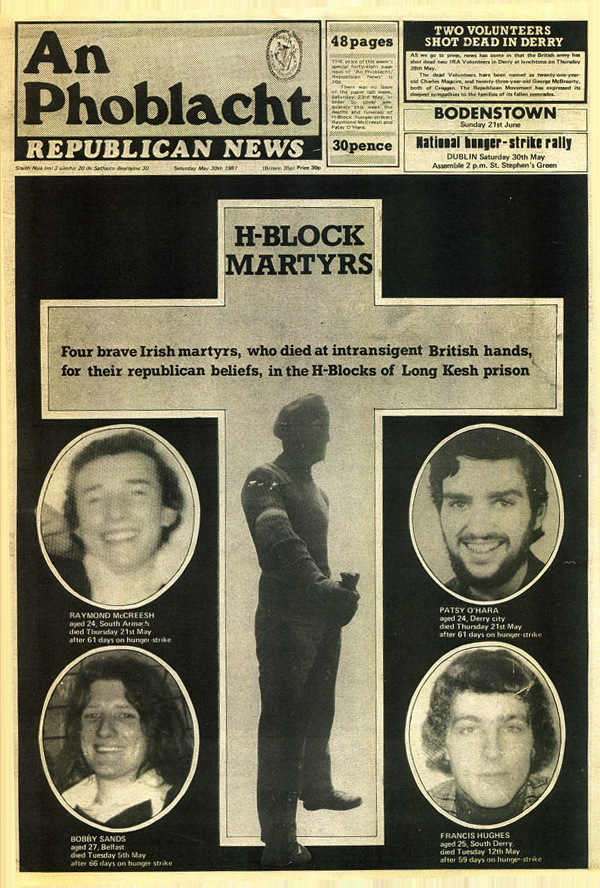

Remembering 1981: Four men dead as crisis escalates

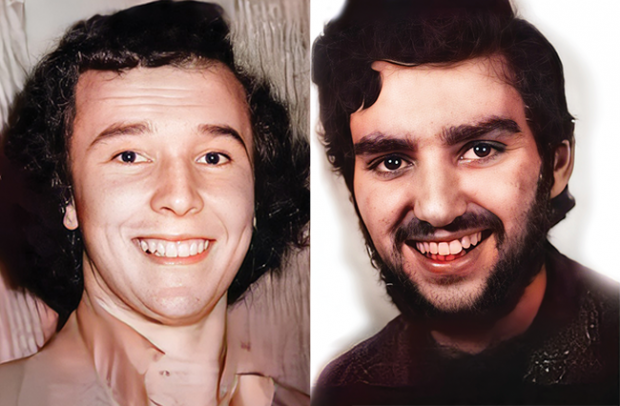

• Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O'Hara

Thursday, 21 May 1981, witnessed the deaths of two more Hunger Strikers. Raymond McCreesh passed away at 2.30am. Later that evening Patsy O’Hara died.

A Mass had been celebrated at Raymond McCreesh’s bedside on Wednesday evening by his brother Fr Brian McCreesh. He was semi-conscious and appeared to show some sign of recognition but died just a few hours later. His remains were returned to his beloved Camlough in South Armagh for the funeral the following Saturday.

Leaving the family home in St Malachy’s Terrace, the cortege stopped briefly at the lane outside the house where it was joined by a honour guard of IRA Volunteers, Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann. Led by a lone piper, the cortege paused to allow Raymond McCreesh’s comrades fire a final salute over the Tricolour-draped coffin.

• IRA Firing party for Volunteer Raymond McCreesh

At St Malachy’s church loudspeakers broadcast the Mass to a huge crowd of mourners. Mass was concelebrated by five priests led by Raymond’s brother Brian. In his sermon Fr Wolsey criticised the British for selectively quoting from the Pope’s 1979 Drogheda speech: “Violent means must not be used, the Pope says, to change injustices. But neither must violent means be used to keep injustices. The Pope has said so. The first passage has been over quoted; the second one rarely heard.”

• Raymond McCreesh’s coffin, flanked by an IRA guard of honour is shouldered by his brothers Malachy and Brian

After the Mass, the funeral procession made its way the short distance to the cemetery where, in sight of the family home, the coffin was lowered into the grave. Chairing the graveside ceremonies was South Armagh republican Joe McElhaw. Defying a British exclusion order, Sinn Féin President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh delivered the oration. Paying tribute to McCreesh, he said: “We are gathered here to perform a last, sad but proud duty for that great Irishman and human being, Raymond McCreesh.” He detailed McCreesh’s progression from Na Fianna Éireann to the IRA and his capture in 1976 after a gunbattle with the British army. He had fought imperialism, which was the “enemy of mankind”.

Ó Brádaigh outlined the area’s proud history of resistance to British rule. He accused the British Government of callously murdering McCreesh and his comrades but added that British policy was now in ribbons. “Where now is their Ulsterisation? Where now was their normalisation? Where now is their criminalisation?” he asked.

“These hungry and starving men in their beds of pain, by superior moral strength, have pushed the British government to the wall and have shamed them in the eyes of the world”, said Ó Brádaigh.

Comparing the Hunger Strikers to Terrence Mac Swiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork who died on Hunger Strike in 1921, he pledged that republicans would continue their resistance to British rule.

PATSY O’HARA

Patsy O’Hara passed away at 11.39pm. By his bedside were his father James, his sister Elizabeth and family friend James Daly. Speaking of his final moments his sister said: “My Father called, Patsy! And he sort of, as if he recognised the voice, sort of just tried to move his head, just one last time. And then he died. And as he was dying his face just changed, he had a very, very distinct smile on his face which I will never for-get. I said, you’re free Patsy. You have won your fight and you’re free. And he was cold then.”

Former leader of INLA prisoners in the H-Blocks, O’Hara came from a staunchly republican family and was much respected in his native Derry. The night of his death saw sustained rioting on the streets of Derry. The RUC replied with volleys of plastic bullets, murdering 45-year-old Harry Duffy in the process. Two days earlier they had murdered 12-year-old Carol Ann Kelly in Twinbrook.

Repeating their actions with the Francis Hughes cortege, the RUC hijacked O’Hara’s remains. Long Kesh Governor Stanley Hilditch had informed the family that the remains had been taken to Omagh where they could be collected. About 4.30am the RUC phoned Derry with a mes-sage. “If you want to collect this thing you had better do it before daylight.” They were determined to prevent a daytime cortege. In a sickening development it emerged, after the body was finally retrieved by the grieving family, that the RUC ghouls had mutilated the body.

• Patsy O’Hara pictured in his prison cell just one week before he died and on the day before Francis Hughes’ funeral. The film was smuggled out but unfortunately the camera and a miniature tape recorder were apparently discovered by the prison authorities two days later in the cell of Raymond McCreesh

The funeral, the biggest in the city since the Bloody Sunday funerals, was addressed by a number of people. Chairing the proceedings was James Daly, husband of murdered anti-H-Block activist Miriam Daly. He offered his condolences to the family before introducing a member of the INLA leadership who read out a statement. Patsy’s brother Seán then addressed the mourners. He compared Charles Haughey to Pontius Pilate and said the Hunger Strikes were an important victory for the cause of Irish freedom as the whole world could now see the callousness of the British.

Gerry Roche of the IRSP detailed the harsh experiences, North and South, endured by O’Hara during his short life. Commending his revolutionary spirit Roche said the attempt to criminalise the prisoners was an attempt to criminalise the entire struggle. O’Hara had recognised this and had resisted courageously. “He believed that it is no crime to fight the British occupation forces, but the duty of every Irish man and Irish woman,” Roche said.

An INLA firing party fired a volley of shots over the coffin in a final salute to their dead comrade.

The deaths of McCreesh and O’Hara in the H-Blocks took place against an increasingly violent backdrop outside the prison. The IRA was mounting increasingly effective military operations against the British army, with five British soldiers killed in an ambush at Altnaveigh, South Armagh.

Crown forces attempted to crush rising nationalist anger. In addition to the plastic bullet deaths of Carol Ann Kelly and Harry Duffy, there was a wave of indiscriminate plastic bullet attacks that left hundreds injured, many of them seriously, including Paul Lavelle (15) from Ardoyne who was left in a coma.

The Hunger Strike was causing a huge outcry in the 26 Counties and Taoiseach Charles Haughey was forced to give the impression of doing something, particularly in light of an impending election on 11 June. He promoted as a serious initiative an intervention by the European Commission on Human Rights which amounted to nothing.

• Funeral of Patsy O’Hara, Derry

Just two days before her brother died, Haughey met with Patsy O’Hara’s sister Elizabeth, during which he gave the impression that a development involving Europe was imminent and asked her for a contact number at which she could be reached. The following morning she got a call summoning her to Government Buildings. Haughey was still pushing the Commission angle but told Elizabeth that Patsy would have to come off the Hunger Strike to give time for a complaint to be made to the Commission. It was clear at this point that the Commission was just a diversion. Elizabeth O’Hara broke off all contact with Haughey.

There was mounting anger on the streets in the 26 Counties. Although the H-Block committee was determinedly non-violent as a matter of strategy, there was a wave of incidents across the state such as the 23 May torching of a bus belonging to English fishermen in Ballinamore, County Leitrim. In a vain attempt to distract from the real issue a Government summit was called with much fanfare to discuss “escalating violence”.

A statement from the Catholic Cardinal, Tomás Ó Fiaich said: “Raymond McCreesh was born in a community that has always proclaimed that it is Irish, not British. When the northern troubles began he was barely 12, a very impressionable age at which to learn discrimination. Those who protested against it were harassed and intimidated. Then followed Burntollet, The Bogside, Bombay Street and Bloody Sunday in Derry all before he was 15.” The Cardinal went on to say that McCreesh would never have been in jail had it not been for the abnormal political situation. “Who was entitled to judge him?” he asked.

The 20 May local elections in the Six Counties saw a number of H-Block candidates elected. Amongst them was Raymond McCreesh’s brother, Oliver.

International support for the Hunger Strikers soared. There were daily demonstrations in the United States. Thousands marched in protest through New York on the Saturday after the deaths of McCreesh and O’Hara. Amongst the countries that saw demonstrations, many of them large, were Australia, Norway, Greece, France and Portugal.

The deaths of Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O’Hara, who had started the strike on the same day, died on the same day and were born within a fortnight of each other in February 1957, marked a critical escalation in the prison struggle, as well as the struggle outside the prisons walls.

RAY McCREESH

• Raymond McCreesh pictured in 1975

Raymond McCreesh was born in the village of Camlough in South Armagh, the second youngest in a family of four brothers and three sisters. After leaving school, he attended Newry Technical College, and served an apprenticeship as a sheet-metal worker.

In June 1976, at the age of 19, McCreesh was arrested after a shoot-out between the IRA and the British Army near Beleek in South Armagh. After nine months on remand he was sentenced in a non-jury court in March 1977.

By the time he embarked on the historic 1981 hunger strike, Raymond McCreesh had spent four years on the blanket protest, and during that time forfeited his visits rather than wear the prison uniform for the half-hour per month. He only took his first visit with his parents in 1981 to inform them that he was going on the hunger strike.

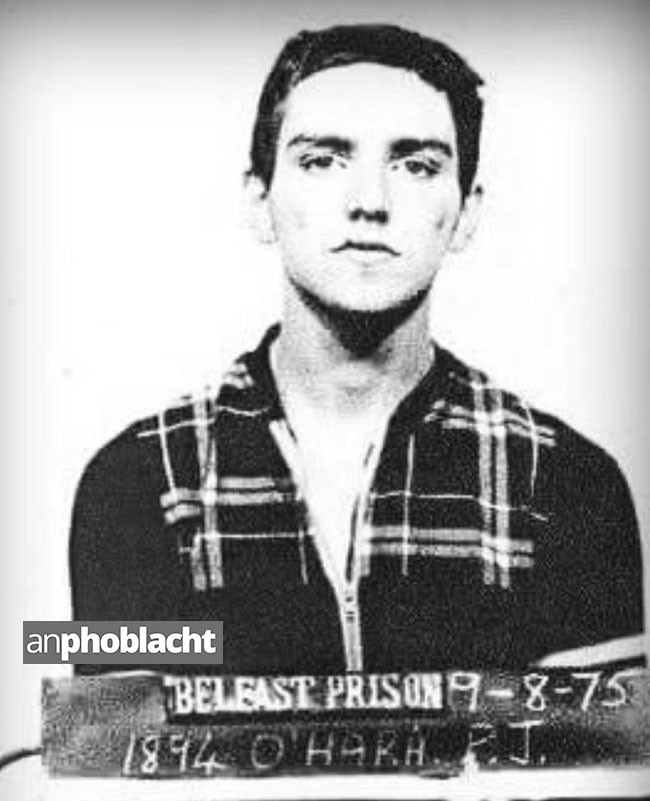

PATSY O’HARA

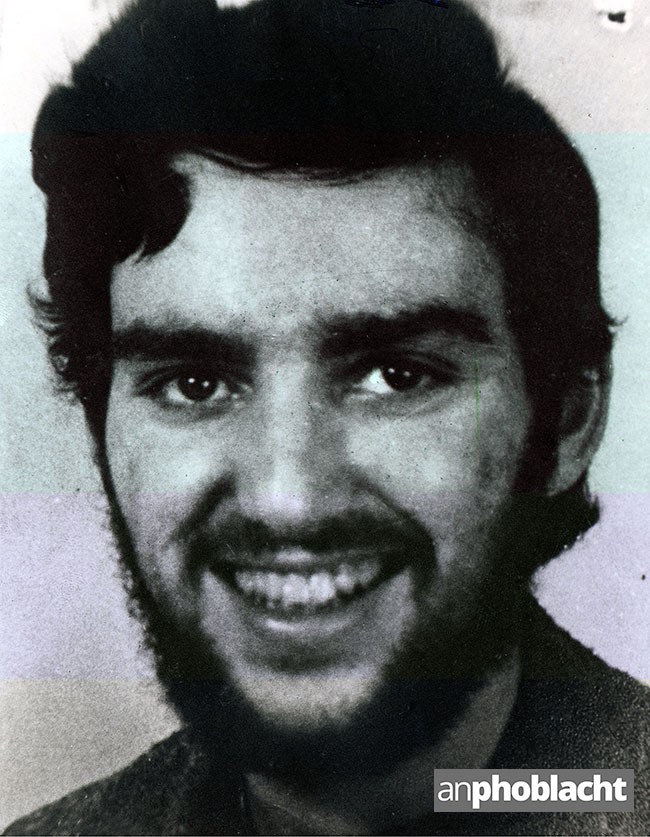

• RUC mugshot of INLA Volunteer Patrick O’Hara from 1975

Patrick O’Hara was born in Derry city on 11 February 1957. He was just 11 years old on 5 October 1968 when, along with his parents, he took part in the big civil rights march in Derry which was viciously attacked by the RUC. A year later he again witnessed one of the milestones in the conflict when the RUC invaded, and were defeated, during the Battle of the Bogside in August 1969.

Patrick, known to everyone as Patsy, joined na Fianna Éireann in 1970 and, although under-age, he joined Sinn Féin in early 1971. A few months after the introduction of internment his eldest brother Seán was interned.

In 1974 his home was continually raid-ed by the British Army and he was frequently harassed and beaten up by them before being interned in October. After his release in April 1975, O’Hara joined the Irish Republican Socialist Party, but within two months he was re-arrested and framed by the British Army. He spent ten months on remand before being acquitted.

The British Army and RUC continued to harass the O’Hara family in 1976 and Patsy’s brother Tony was arrested and charged with a political offence for which he was subsequently convicted on the basis of an alleged verbal statement.

Patsy was arrested again in September 1976 and charged with possessing arms and ammunition. This was really internment-by-remand and he was released after four months, when the charges were dropped.

In June 1977 he was arrested in Dublin, interrogated for seven days, and charged with holding a Garda at gunpoint. He was released on bail six weeks later and in January 1978 he was acquitted.

Patsy was arrested once more in May 1979. He was charged with possession of a hand grenade and was convicted on the basis of accusations made by two British soldiers. He was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment in January 1980 and immediately went on the blanket protest.

This week 25 years ago saw four young men, from various parts of the Six Counties, on a hunger strike to the death in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, as the republican leadership urged the need for mobilisations and action in support of their demands for recognition as political prisoners.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures