1 December 2020 Edition

Reporting in a War Zone

• Photo shows British Army barricade between the City Rates Office (right) and City Hall (out of picture on left) guarding entrance to Dublin Castle (top left)

I went from being Chris Graham, newly released Mountjoy POW to reporter Maeve Armstrong – my by-line with Republican News from 1978-89. The name held its own wee story. Maeve, well, the Irish Warrior Queen herself no less! I was living in a war zone so it might be handy to have a warrior around me and Armstrong, that was my wee granny Julia’s maiden name. She was my real-life heroine, so between the two names, I hoped the strength of character they both encapsulated might rub off on me!

Little did I know what I was getting into joining the ‘Rep News’ as we called it.

I’m rushing ahead – it hadn’t been my plan to join the paper when I got out of Mountjoy in March 1978 – I’d gone into gaol at 19, one of the Cork 7 republicans tried in Dublin’s Special Criminal Court for possession of explosive components. Being the only woman in the group, I went to Mountjoy, the others to Portlaoise.

Officially, there was no political status as such in Mountjoy so, as the only political prisoner there, I had to assert my political status every day until the regime begrudgingly acknowledged it.

In the North’s prisons, it was a different story as our prisoner’s political status was removed to criminalise them and our struggle. The rest is history - H-Blocks, two hunger strikes, mass mobilizations on the streets, dead comrades and civilians, the rise of Sinn Féin, its democratic mandate secured, peace process – a tide turned forever in our struggle towards Irish reunification.

When I was released and headed north to West Belfast, it was with a mind to defending our areas and our people again. So, when instead I was asked to take care of the security of the “Rep News” staff in order for the paper to be produced and circulated, I must admit I was a little perplexed.

I clearly had a lot to learn about the significance of publicity in the struggle. I became a fast learner – the paper was underground, hounded by the Brits who wanted it silenced or at the very least, seriously disrupted. Collectively however, we weren’t going to let that happen. The voice of the oppressed – when it is provided a platform – is more powerful than any amount of repressive legislation or the lies of establishment spin doctors.

I met Rep News’s motley crew who included among others Belfast republicans Jim Gibney, writer, and Danny Devenny (layout artist) – absolute salt of the earth. Danny Morrison too who merged the paper with An Phoblacht in January 1979 – a smart move.

The paper had to be produced from a series of safe locations in Belfast because it had been shut down and several people, including Danny Morrison, arrested. The paper was literally produced on the hop – it was my responsibility to secure and organise a safe operating network around the paper’s team. I also ensured the mock-ups got to the printers every week – others dealt with distribution across the North.

This was a logistical challenge at times because there was always the threat of the Brits/RUC finding out which venue or home we were using. Sometimes, areas would be swamped with crown forces and there were some near misses regarding deadlines being met which delayed printing. Those good folks who opened up their doors to facilitate the paper getting onto the streets risked being arrested or worse, being set up for reprisals later on.

At that stage, I wasn’t formally writing for the paper – I would transcribe the Comms coming into us from the prisoners in the H-Blocks and Armagh. The most powerful emotional memories I have to this day is about opening several of the comms with their tiny writing on toilet roll paper from Bobby Sands.

You were the first person to see his words - and hear his voice as I imagined it in my head - graphically describing that prison hell he and his comrades were experiencing every day in the H-Blocks. Having been so soon out of prison myself, it tore through my heart and soul reading ‘I am Sir, you are 1066!’ first published in Republican News July 1st 1978 or ‘I fought a monster today’ October 7th 1978. (The Comms were signed Marcella, his sisters name so we knew they were Bobby’s.)

Richard McAuley, Northern Editor of the paper for a time - and my husband for a time too - was mostly responsible for encouraging me to write more for the paper as I’d dipped my toe into doing some harassment stories.

You just did whatever was required, I would also work as typesetter on An Phoblacht in Dublin, working through the night, getting a few hours’ sleep on a sleeping bag on the office floor and then the train back to Belfast to begin all over again.

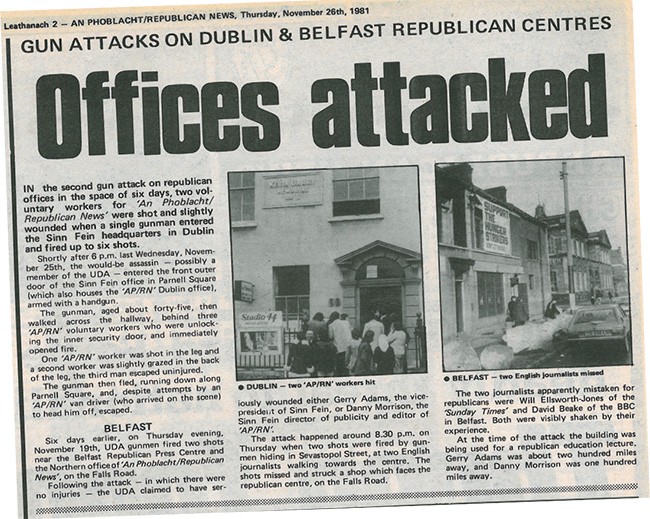

Layout Artist, Danny Devenny was shot in the leg by a UFF gunman in 44 Parnell Square, Dublin

One night, Danny Devenny was shot in the leg by a UFF gunman in the hallway of Parnell Square while I was upstairs typesetting. I was heavily pregnant at the time. You didn’t think risk, just that Danny was ok and got to hospital – I told Mick Timothy our editor to tell Ruairí Ó Brádaigh that we weren’t letting the Gardaí in to question us. It would delay the paper and anyhow, the Gardai who were usually camped outside the building probably had a ringside view of everything that happened and didn’t stop it.

It would be impossible in this short piece to describe the range of issues and political events which are historically significant which I covered in my role as Maeve Armstrong but essentially I didn’t do things by half – I would dig into issues, suss out eyewitnesses and ensure as far as possible that their testimony was substantiated, because I knew that the establishment media and the Brit propaganda machine of the NIO was always poised to discredit our accounts of events.

I travelled everywhere around the North meeting hundreds of people affected by the conflict and giving voice to the social economic poverty they experienced. I also covered the whole hunger strike periods and had access to many of the relatives, friends, and comrades as I pieced together the profiles of these heroic young men who had taken on to fight the monster from inside their prison cells.

One of the most enduring memories caught in slow motion in my mind is of Owen Carron, sitting in my home shortly before going to see Bobby Sands. Back and forth, he brushed and polished his shoes amidst the silence of all around him, a silence before the storm that was to be brought upon us by Thatcher’s vicious decision to let Bobby die.

That period in our history is for many of those who lived through it, including myself, still far too horrendous to fully recount. The amount of activism on the streets by extraordinary, ordinary people and the brutal response of the British Army and RUC was horrendous. We could not keep up with the scale of incidents which needed reported.

In the years that followed, I covered many of the shoot-to-kill incidents around the Lurgan and Portadown areas – we would often be tailed in and out of the areas by undercover units. One time, we were stopped and myself and the driver taken into Lurgan RUC barracks – they wouldn’t let me go to the toilet. After several requests, I warned them I would need to go - I did. We were thrown out 5 minutes later!

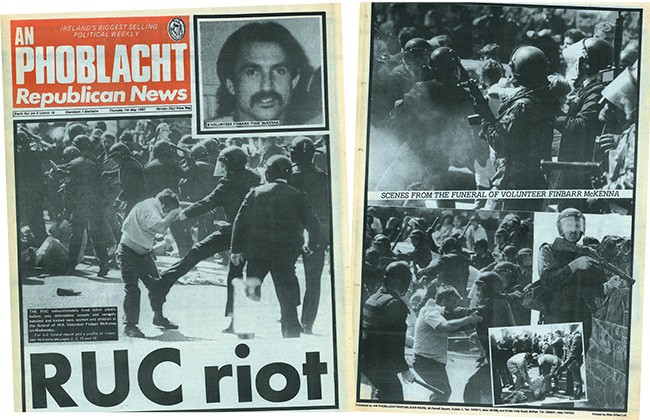

Battle of the Funerals – RUC and Brits attack the funeral of IRA Volunteer Finbarr McKenna

Yes, it could get a bit dodgy writing for the paper. I was covering the republican funeral of Volunteer Finbarr McKenna who died on active service on 2nd May 1987. This was the period known as the Battle of the Funerals when the RUC, clad in full riot gear, supported by the British Army, endeavoured to inflict maximum intimidation and saturation techniques to try and deter people from attending republican funerals.

It was a grim time for mourners and a disgusting tactic to use against grieving families who had lost their loved ones. That day at Finbarr’s funeral, they attacked us with plastic bullets and batons, charging at young and old and stampeding people who fell on top of each other.

I only remember thinking “I’m gonna die at a funeral” before the darkness enveloped me. The next thing I heard was “There’s a girl under here!” before I took a breath and got pulled out by the ankles.

Thank you Joe Leatham from Poleglass and Bernard Fox from St James’s. But that wasn’t the end of it – my glasses and my tape recorder were broken, I had no shoes and just across from me my poor dad Sam Graham, was being kicked mercilessly by the RUC. I went berserk and got him away from “the farces of law and disorder” as my dad would rightly call them.

What amazed and humbled me every time was the dignity of our people in the face of some of the most horrendous treatment at the hands of the Brits and RUC.

The use of plastic bullets to terrorise ordinary people from going on protests was not just confined to that – they also shot those weapons indiscriminately at passers-by as they patrolled our areas. A member of the Royal Anglian Regiment, sitting safely in his armoured personnel vehicle, opened up and shot little 11 year-old schoolboy Stephen McConomy from Derry on April 16th 1982. He was in the street, innocently playing with his friends. There were no disturbances in the area at the time.

I will never forget the beautiful wee face of Stephen, his entire head wrapped in white bandages and tubes and wires trying to keep him alive for the three days he lay motionless in Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital. Having two young children at the time myself, I especially connected with the anguish of Stephen’s distraught mother, Maria.

Stephen’s uncle, the late Michael Sweeney and his Auntie Rhona Toland also kept vigil and I had the privilege to look after them at my home too when they needed a short break. Can you imagine what it was like for them to watch while armed British soldiers and RUC walked into the intensive care unit while Stephen, an innocent child, fought for his life?

That’s how it was. So, when Maria asked me to take a photo of Stephen on his life support and get it to the media, the job was done. There was mayhem in the intensive care unit as the staff and RUC demanded the camera off me, threatening me with arrest.

11 year-old schoolboy Stephen McConomy killed by a British plastic bullet in 1982

The family, dignified but determined, stood their ground and insisted they had authorised the photo. It was intense - and as they say, a photo tells a story better than a thousand words. Stephen’s battle for life tragically ended when he died without gaining consciousness from his head wound but his iconic image was transmitted worldwide.

At a time when British propaganda had unlimited resources aimed at labelling us “criminals and terrorists” it was vital in my view that our truth had its own pathway of expression through our own paper and publicity outlets.

Stephen McConomy’s life force was slipping away because a British soldier, safe inside his personnel carrier, fired a plastic bullet at young Stephen’s head – he knew he could get away with it.

Today, that soldier and the rogue state actors who armed him with such lethal weapons continue to act with impunity and immunity. The British Ministry of Defence can hold onto “classified files” relevant to plastic bullets which could assist Stephen’s family in obtaining a fresh inquest into his death.

Those files can remain shut until 2071, nearly 100 years after Stephen’s death – that in itself should demonstrate, if nothing else does, the kind of monster which many in our communities have been dealing with and continue to deal with in trying to gain justice and truth from the British state.

It is why, nearly 100 years on since the partition of our country, that we need our nightmare to end and a new beginning, in a new Ireland for all communities, to come as quickly as possible.