21 December 2020

The Partition plot – hatched in deception, enforced in terror

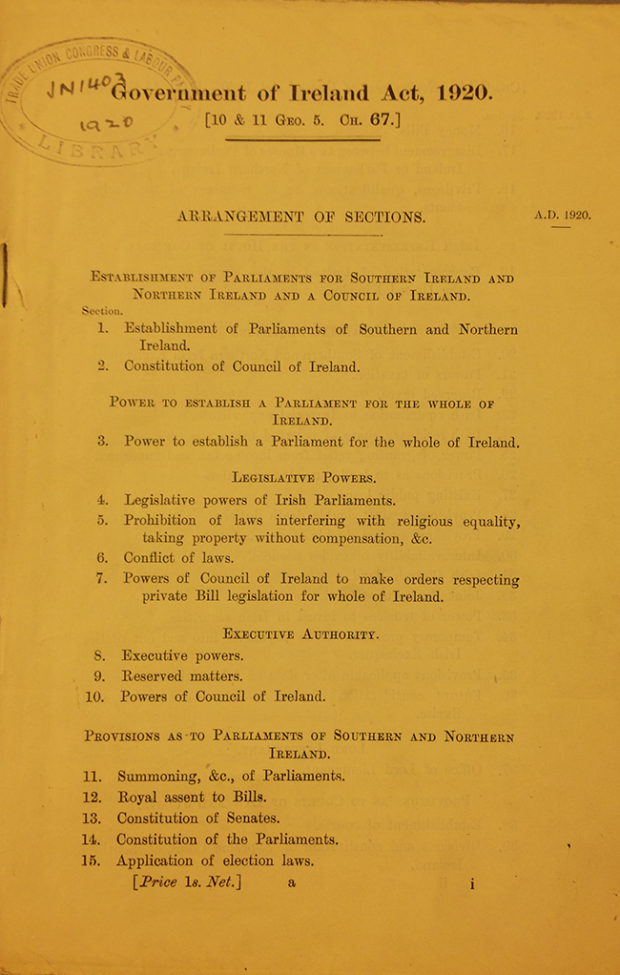

Centenary of the Government of Ireland Act

The centenary of the passing of the 1920 Government of Ireland Act falls on 23 December, the day 100 years ago when the legislation received ‘royal assent’ and became law, setting the British legal framework for the Partition of Ireland. The British government plot to divide Ireland was long in the making and it was accomplished by a combination of deception and terror.

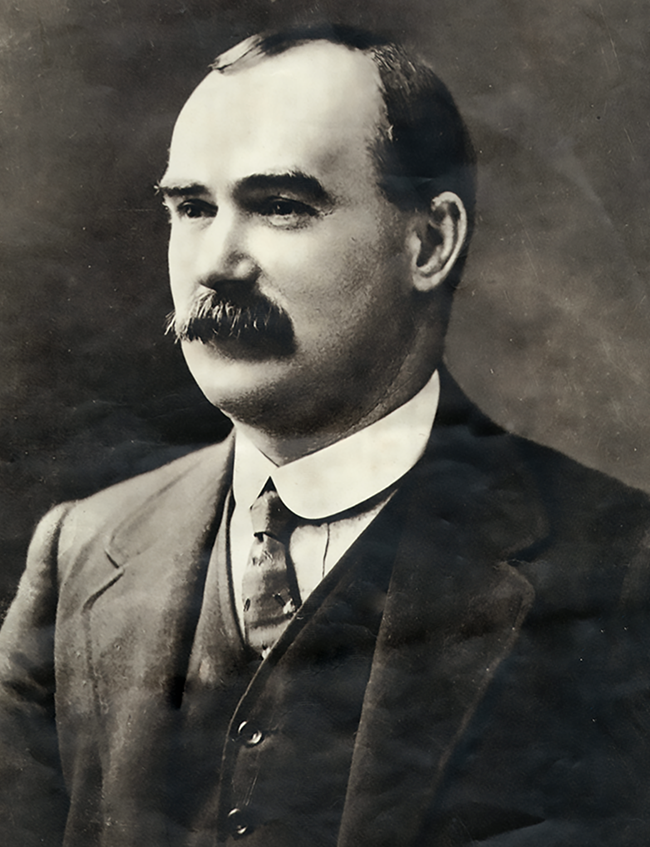

The principle of Partition was first introduced by British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith in the House of Commons when he proposed “county option with a time limit” by which any of the nine counties of Ulster might vote out of Home Rule for a period of six years. Irish Party leader John Redmond accepted the principle of Partition as a temporary measure, leading James Connolly to write that such a scheme “would mean a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the wheels of progress…” and it should be fought “even to the death”. From the beginning nationalists of all shades, as well as republicans and socialists, expressed their opposition to it.

James Connolly

With the outbreak of the First World War Home Rule was ‘placed on the statute book’ but postponed, supposedly until the war was over. John Redmond, based on this promise, encouraged nationalist Irishmen to join the British Army. But the threat of Partition remained and Connolly described the British government’s manipulation of Redmond as “ruling by fooling, a great British art, with great Irish fools to practice on”.

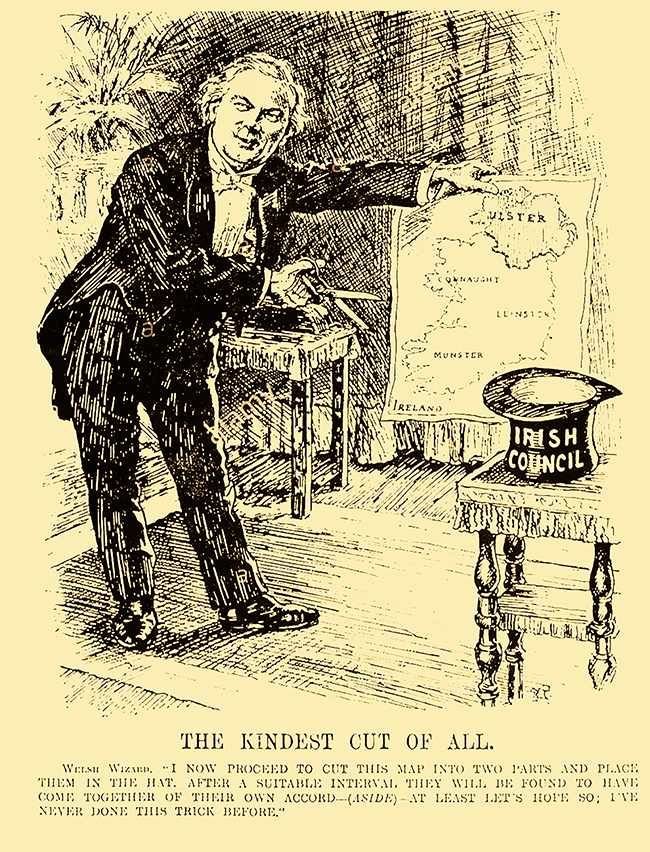

In the wake of the 1916 Easter Rising Asquith asked Cabinet Minister Lloyd George to intervene and attempt a ‘settlement’ - on British terms of course. The priority, with Britain in the depths of all-out war, was to ‘stabilise’ Ireland. In May, a few days after James Connolly’s execution, Lloyd George wrote secretly to Unionist leader Edward Carson on the proposed ‘provisional period’ of exclusion of Ulster from Home Rule: “We must make it clear that at the end of the provisional period Ulster does not, whether she wills it or not, merge in the rest of Ireland.” At the same time Lloyd George was telling Redmond and the nationalists that the exclusion of Ulster counties would be temporary.

Based on the British promise, Redmond and his Belfast lieutenant Joe Devlin MP called a convention of nationalists of Ulster to endorse Lloyd George’s plan. Warnings against even temporary Partition were dismissed by Devlin and the plan was endorsed. But it came apart when Southern Unionists objected to it and Lloyd George had to step back - but only temporarily. In December 1916 he became British Prime Minister and early in 1917 returned to his Partition plan.

The new British Prime Minister was again playing a double game. The United States was about to enter the First World War on the side of Britain and France. To help ensure full American commitment Lloyd George wanted to placate opinion in the US which was critical of British repression in the wake of the Rising.

In a speech in the House of Commons on 7 March 1917 Lloyd George admitted that “centuries of brutal and often ruthless injustice” had driven “hatred of British rule into the very marrow of the Irish race”. He spoke of Home Rule before the war ended – but only for “that part of Ireland that clearly demands it”. To placate the Conservatives and Unionists in his Cabinet, he said that to place the north-eastern counties “under national rule against their will” would be “an outrage”. Under pressure after the Rising, the executions and the jailing of hundreds of nationalists, and having lost the Roscommon by-election to Count Plunkett, the Redmondites walked out of the House of Commons in protest against Lloyd George’s speech.

In May 1917 on the eve of the South Longford by-election a manifesto against Partition was published and signed by three Roman Catholic archbishops and 15 bishops, three Protestant bishops, as well as county council chairs and other public figures. The manifesto declared:

“To Irishmen of every creed and class and party, the very thought of our country partitioned and torn as a new Poland must be of heart-rending sorrow.”

In such a close election this was a decisive intervention. Polling day was on 9 May and Joe McGuinness won by only 37 votes. He won despite an outdated electoral register, the local strength of the Redmondite party and press hostility. The Times of London described it as “a most damaging defeat” for the Redmondites and added that “no settlement based on the temporary or permanent partition of Ireland can have the smallest chance of success”.

The ‘Irish Times’ said the Partition proposal was now “dead as a doornail and any government which should try to resurrect it would show itself incredibly ignorant or insanely contemptuous of the solitary conviction which now unites all political parties in Ireland”.

But once again Lloyd George stepped back, only to revive his plan a third and final time. He did this after Sinn Féin won an overwhelming mandate for an undivided Ireland, an Irish Republic, and established Dáil Éireann in January 1919. The Dáil was banned in September and in December the Government of Ireland Bill, which provided for Partition, was introduced in the House of Commons. It was the product of a committee chaired by Unionist Walter Long. It partitioned Ireland, providing for a parliament each for ‘Northern Ireland’ and ‘Southern Ireland’ with a token ‘Council of Ireland’. Long made clear to the Cabinet that the priority was to maintain the whole of Ireland in the British Empire.

While the Bill was making its way slowly through the British Parliament the conflict in Ireland was intensifying politically and militarily. In local government elections across the 32 Counties, held using proportional representation in January and June 1920, Sinn Féin made major gains, including in Ulster where nationalists and republicans win control of Derry Corporation and Fermanagh and Tyrone County Councils.

In May 1920 Unionist leader Edward Carson in the House of Commons accepted that the partitioned area would be six counties, not all nine Ulster counties. He said:

“We should like to have the very largest area possible, naturally. That is a system of land grabbing that prevails in all countries for widening the jurisdiction of the various governments that are set up; but there is no use in undertaking a government which we know would be a failure if we were saddled with these three counties.”

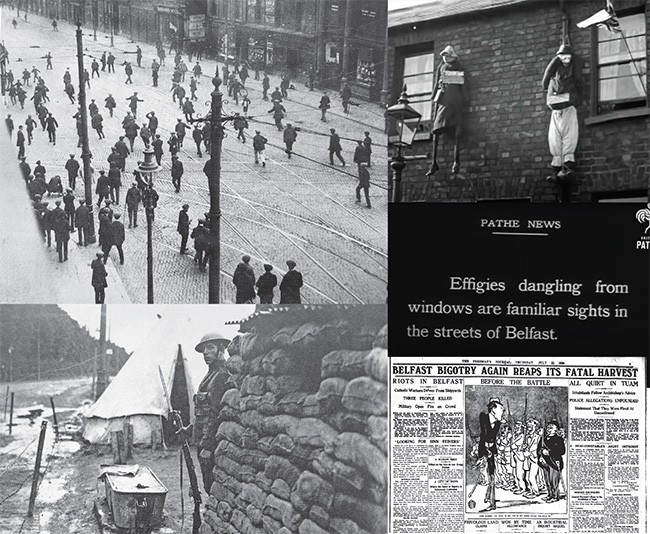

July 1920 saw the start of the Belfast Pogrom when sectarian Unionist mobs, including armed Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) members, drove an estimated 10,000 workers from their jobs because they were Catholics, with selected Protestant trade unionists targeted as well. Hundreds of Catholics were driven from their homes and businesses. The Pogrom continued in the following two years and between July 1920 and July 1922 nearly 500 people were killed in Belfast. 60% of the dead were Catholics, though they made up just 30% of the population. The Pogrom was fundamental to the foundation of ‘Northern Ireland’ as a sectarian state where the minority was to be terrorised into submission. This was seen clearly when the Ulster Special Constabulary was established in November, including thousands of UVF men.

The Government of Ireland Act became law on 23 December 1920, after the two fiercest months of the war. Four counties were under martial law. The centre of Cork lay in ruins, having been burned to the ground by British crown forces. Dubin city was in the grip of fear with nightly curfews, its City Hall and other civic buildings occupied by the British Army. Across the country British terror was being met by IRA resistance as flying columns became more organised and effective.

Soon there would be peace moves and eventually, in the summer of 1921, a truce and peace talks. But the British government’s plot to divide Ireland and keep its imperial grip on the island was coming to fruition with tragic consequences that would last for decades.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures