2 March 2012 Edition

Uncomfortable conversations are key to reconciliation

INCREASING UNDERSTANDING AND MUTUAL RESPECT BY REACHING OUT TO UNIONISTS

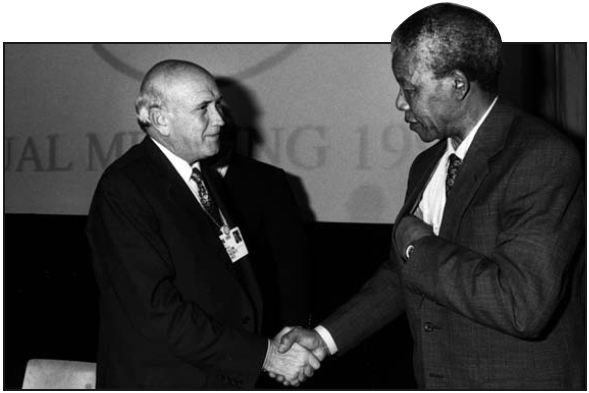

• South Africa’s de Klerk meets Mandela: Initiatives in the interests of reconciliation are crucial

We need to be prepared to take the lead in helping to shape an authentic reconciliation process and embrace the discomfort of moving outside our political and historic comfort zones. We need to be courageous

MANY YEARS AGO, unionists told republicans that our words could not be heard over the sound of guns and bombs. That was in a period when republicans sought contact and dialogue with unionist and Protestant people against the backdrop of the IRA’s ongoing armed struggle.

The willingness of those unionists to engage was a tribute to their personal courage at a time when they could have risked being ostracised within their own communities.

Now, with the benefit of hindsight provided by our peace process, their assertions have been proved right. It is bound to be more difficult to contemplate taking the initial steps towards peace in the midst of war. This is relevant for republicans committed to moving forward in the peace process and encouraging a discourse on the achievability of a united Ireland.

Our party is committed to anti-sectarianism and the creation of an inclusive, pluralist united Ireland. That, in turn, places the responsibility upon republicans to persuade and convince all sections in our society of its desirability.

Increased dialogue and engagement with the wider unionist and Protestant community is essential. And this poses a massive challenge to republicans. Why? Because it means being prepared to set aside our own assumptions about the nature of that dialogue in order to better understand the fears and apprehensions of Protestants and unionists — and to listen unconditionally to what they have to say.

We need to be prepared to take the lead in helping to shape an authentic reconciliation process and embrace the discomfort of moving outside our political and historic comfort zones.

We need to be courageous.

A deep suspicion remains within unionist communities towards republicans due to the legacy of the armed struggle. Real hurt exists on all sides.

Republicans have a vision of a society beyond our conflict resolution process. We speak about nation building but we need to be prepared to define engagement in terms beyond what suits ourselves. Engagement is not a strategy to make unionists into republicans.

Our aspirations to achieving reconciliation and trust will be fettered unless we take on board the import of legacy issues and continued suspicion within the wider unionist and Protestant community. Reconciliation means being willing to have uncomfortable conversations.

We should reflect upon what all that means and what is required to overcome entrenched sectarianism and community division in the North. Then we need to think even deeper how to address the gulfs in life experience and perception between local communities across the island. The difference between Ballyclare and Ballyheigue is much more than geographic distance.

This is a time for republicans to free up our thinking, to carefully explore the potential for taking new and considered initiatives in the interests of reconciliation.

The process of uniting Ireland will be built on increased understanding and mutual respect by reaching out, healing differences, and creating trust with unionists and Protestants.

We should be prepared to go the extra mile. That means listening, which in turn means not only seeking to persuade but also being willing to be persuaded.

Republicanism needs to become more intuitive about unionist apprehensions and objections, and sensitised in our response. We need to be open to using new language and consider making new compromises.

Regardless of the stance of others, we should recognise the healing influence of being able to say sorry for the human effects of all actions caused during the armed struggle. All sensible people would wish it had been otherwise, that these events had never happened, that other conditions had prevailed. The political reality is those actions cannot be undone or disowned. It would be better they had never happened.

Armed struggle is not a point of principle or an end in itself. It arose from political conditions, as a last resort and those conditions no longer exist. Yet the consequences have to be dealt with. The legacy of our conflict and the creation and perpetuation of the conditions which gave rise to it need to be addressed. Through meaningful dialogue, however, we can all seek to better understand the respective experiences of each other. Now the conflict is over, the imperative of creating a better society at ease with itself is a new challenge for us. And republicans should approach that laborious work with compassion and imagination. It requires bravery to take risks in struggle but it takes exceptional moral leadership and self-belief to build a real reconciliation process, one with the ability to help overcome the hurt caused by armed struggle.

That’s why we must ensure our engagement is based upon listening carefully to unionists and others and develop the capacity to explore what more can be done to help meaningfully heal our society’s divisions. Dialogue, using new language and making new compromises to create trust, are the seeds of nation building.

Facing these issues and grasping their implications are fundamental to the process of uniting Ireland. The challenges arising for republicans are significant but the importance in taking forward this work is greater still.