21 November 2020

From Amritsar to Croke Park to the Bogside

Remembering the Past – Bloody Sunday Centenary Part 2

Newspaper headlines after the Croke Park massacre on Bloody Sunday 1920 compared it to Amritsar in India when the year previously the British Army had murdered hundreds of civilians at a site where, as in Croke Park, thousands of men, women and children were assembled. In both cases the British government tried to cover up the truth about a crime that was an act of terror against a people seeking independence and which was fueled by racist contempt for the victims.

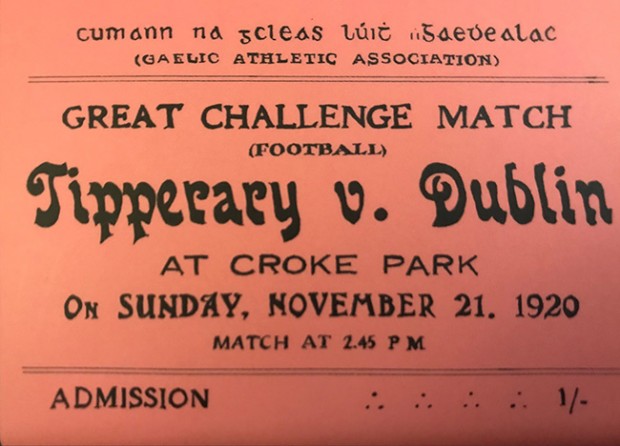

Dublin and Tipperary were scheduled to play a challenge Gaelic football match at GAA headquarters, Croke Park, Jones’s Road at 2.45pm on Sunday 21 November 1921. After the execution of British agents in the City that morning, and acting on information received from an IRA mole in the DMP, the IRA informed Luke O’Toole of the GAA that the crown forces might target the crowd at the game and it would be advisable to postpone it. However, people were already in the ground and many more were arriving so O’Toole considered it would be more dangerous to call it off and the game went ahead as planned.

Michael Collins, Luke O’Toole and Harry Boland

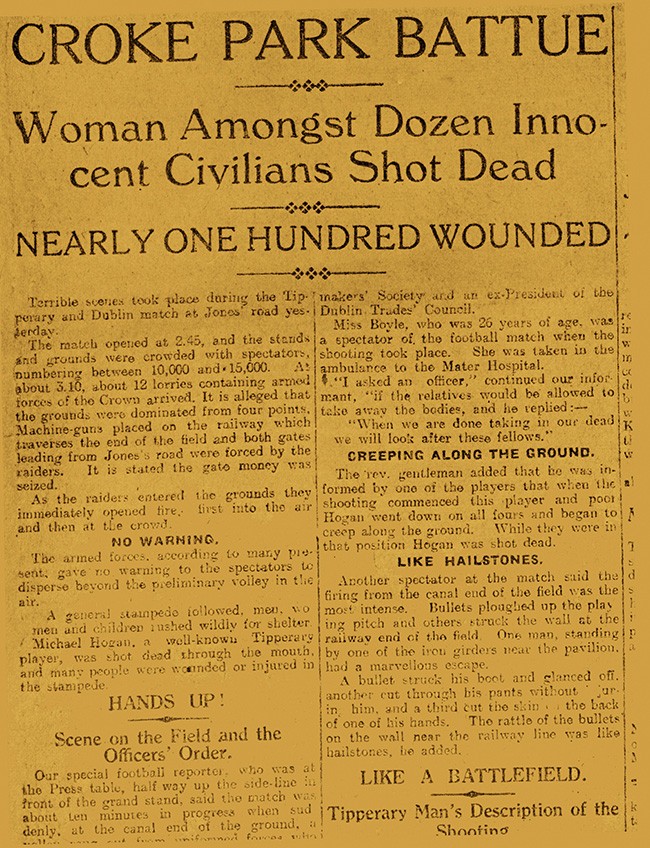

In the afternoon a major British operation began involving Black and Tans, Auxiliaries, regular RIC and British troops who descended on Croke Park. The operation was supposedly to stop and search people coming out at the end of the match. This was to be done by the Tans, Auxies and RIC while the British Army cordoned off the area and stood guard. The match began half an hour late at 3.15pm and shortly afterwards the British crown forces arrived and surrounded Croke Park. But there was to be no ‘stop and search’.

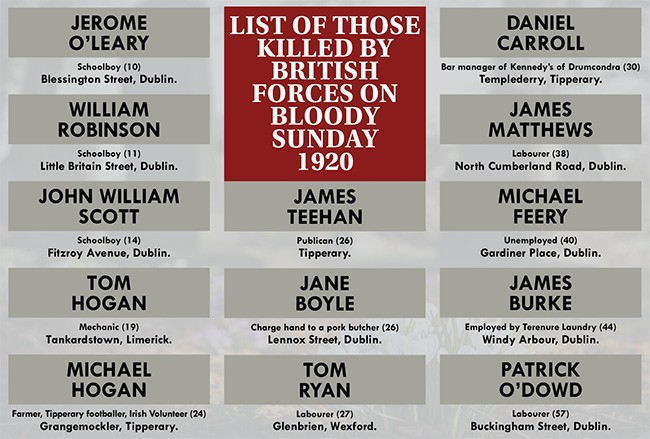

Almost as soon as the crown forces arrived the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries began firing into the crowd and at the players on the field. One of the first killed was William Robinson, age 11, who was watching the match from the branches of a tree. The youngest victim, Jerry O’Leary, was a year younger. The one woman killed was 26-year-old Jane Boyle who was due to be married later that week. Tipperary footballer Mick Hogan was shot dead on the field and when Thomas Ryan tried to whisper an Act of Contrition in Hogan’s ear, he too was shot dead.

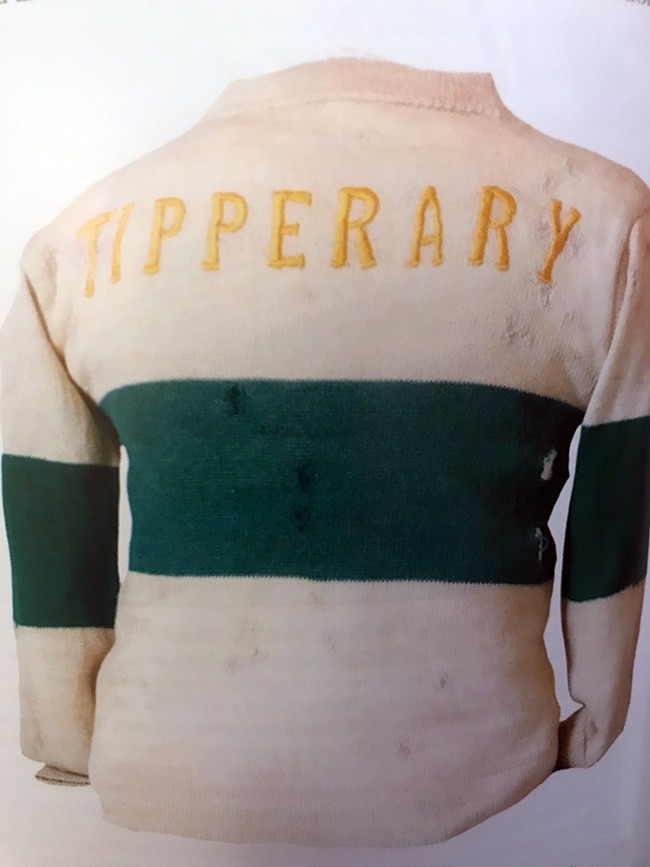

Tipperary footballer Mick Hogan’s jersey

There was blind panic as the crowd tried to flee the gunfire. People jumped from high walls. Children – including this writer’s grandfather, eight-year-old Thomas O’Connor - were dropped from the wall into the arms of men below. A surge from the ground turned into a retreat when the fleeing people were confronted with crown forces, resulting in a terrible crush causing more death and injury. The death toll reached 14.

Almost as soon as the massacre was over, the lies began. British propagandist Basil Clarke in Dublin Castle issued an ‘official account’ to the press. It claimed that the purpose of the British operation was to search the crowd for members of the Tipperary IRA which “was known to include some of the most desperate characters in that organisation” and that a search for arms “might result in the identification of some of these men with the morning’s assassinations”. This was the pretext. The excuse for the murders was later described by the GAA as “too ridiculous” to consider. Clarke claimed that “before the cordon was completed police were fired upon by Sinn Féin pickets at the entrance of the field...the police returned fire with the result that ten persons were killed and eleven seriously wounded”.

Croke Park in the aftermath of the shootings

Like the lies issued after the massacre in Amritsar in 1919 and after the Bloody Sunday massacre in Derry in 1972, the lies about Croke Park were issued in the immediate aftermath to try to absolve British forces of responsibility and to get the ‘official account’ into the world’s press before the real witnesses could speak. Clarke’s fiction was repeated in the House of Commons by the head of the British regime in Ireland Hamar Greenwood. Official but secret inquiries that followed were engineered to concoct ‘evidence’ to support the initial lies.

The façade of lies soon crumbled, however. Even elements of the British press were skeptical from the beginning about the ‘official account’ with The Times of London running critical pieces and making the Amritsar comparison. The British Labour Party’s Commission of Inquiry into Conditions in Ireland rubbished the excuses of Clarke and company and strongly condemned the crown forces. And most damning of all, Frank Crozier resigned as head of the Auxiliaries, citing Croke Park as one of the atrocities which prompted him to leave and denying the ‘official account’.

Before the shooting began at Croke Park that Sunday afternoon a British military airplane from Collinstown aerodrome (now Dublin Airport) flew low over Croke Park and released signal flares. These were the early days of aerial warfare but already colonised people like the Indians and the Irish knew the menace of such machines in imperialist hands. The day after the Amritsar massacre, on 14 April 1919, a British plane flew over the town of Gujranwala in Punjab and dropped bombs and machine-gunned more innocent men, women and children. Brigadier-General D.H. Drake Brockman of the British Army commented:

“Composed as the crowd was of the scum of Delhi city, I am of firm opinion that if they had got a bit more firing given them it would have done them a world of good and their attitude would be much more amenable and respectful, as force is the only thing an Asiatic has any respect for.”

It was the same mentality of the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries in Croke Park in 1920 and of the Parachute Regiment in Derry’s Bogside in 1972.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures