24 October 2020

Terence MacSwiney, Ireland and the world

Remembering the Past – Terence MacSwiney Centenary

The story of Terence MacSwiney’s hunger strike has been told many times, in the pages of An Phoblacht and elsewhere. That it still carries such power and resonates to this day shows what an epic struggle it was. One Irish political prisoner was alone in the heart of the British Empire and fighting that Empire with only his determination and his body as weapons. His death and the national and international response to it proved his own words that “not all the armies of all the Empires of earth can crush the spirit of one true man. And that one man will prevail.”

Perhaps more than any other event during the Black and Tan war the deaths in October 1920 in British custody of hunger strikers Michael Fitzgerald and Joseph Murphy in Cork and Terence MacSwiney in London, expose the hypocrisy of those who would portray them as patriots and their struggle as a war of independence while deeming the IRA hunger strikers of 1981 as terrorists and their struggle as criminal. Terence MacSwiney was an IRA prisoner of war, elected by the people of Mid-Cork, a mandate denied by the British government. Bobby Sands MP (Fermanagh-South Tyrone) in 1981 was in the same position, as was his fellow hunger striker Kieran Doherty TD (Cavan-Monaghan) and their prison comrade Paddy Agnew TD (Louth).

There are other uncomfortable parallels for the political establishment in the 26 Counties. The new Free State government allowed MacSwiney’s Cork IRA comrade Denis Barry to die on hunger strike in November 1923 and the Catholic Bishop of Cork, Cohalan, who had attended MacSwiney’s funeral, ordered that no church in his diocese should permit Denis Barry’s body through the door. In all six IRA hunger strikers died in the 26 Counties, under both Cumann na nGaedhal (later Fine Gael) and Fianna Fáil governments.

After tens of thousands of people turned out on the streets of London to pay respects to Terence MacSwiney his funeral went by train to Holyhead where it was due to be ferried to Dublin. But at Holyhead the coffin was hijacked by the British Army and the MacSwiney family were violently ejected from the train. His sister Mary was thrown to the ground and his brother Seán was struck by a policeman. Yet another uncomfortable parallel for successive Dublin governments when we recall how the Fine Gael-Labour government in 1976 hijacked the body of IRA hunger striker Proinsias Stagg who had died in an English prison. MacSwiney’s body was taken in a ship full of crown forces to Cork where it was released for a republican funeral. The Dublin government went even further than the British as Stagg’s body was flown to Shannon Airport, where relatives were treated in the same manner as MacSwiney’s, and then the hunger striker was buried by the government itself in order to deny his expressed wish for a republican funeral.

In the week we commemorate the centenary of Terence MacSwiney we have seen a Cork Fianna Fáil Taoiseach ruling out a referendum on Irish Unity and refusing even to talk about a United Ireland. And this at a time when both the Brexit crisis and the Covid pandemic have exposed yet again what a crime and a folly the Partition of this island is. Partition was enshrined in British law (the Government of Ireland Act) exactly two months after MacSwiney’s death. For the first time there is an opportunity to work towards Irish Unity in a planned, programmatic way, peacefully and democratically, yet the current Taoiseach is actually pushing hard against it. This should only encourage all who seek Irish Unity to work even more determinedly for that outcome.

In the campaign for Irish Unity we need to show that a post-Partition Ireland will be a better country, a true Republic, with equality at its heart. Terence MacSwiney’s idealism envisaged such an Ireland. He knew it would require vigilance and diligence to ensure that political independence would not be badly used, as indeed it was to be in the Free State. He said:

“That we shall win our freedom I have no doubt; that we shall use it well I am not so certain, for see how sadly misused it is abroad through the world today.”

Looking forward to independence MacSwiney said “we shall take pride in our institutions, not only as guaranteeing the stability of the state but as securing the happiness of the citizens” and he cautioned that “a government that over-rides the weak because it is safe is a tyranny”.

MacSwiney had a clear view of Ireland’s place in the world, a view still highly relevant today. Like James Connolly and Roger Casement he saw a free Ireland helping other oppressed nations and opposing Empires and their war-mongers. His writings today read like a manifesto for independent foreign policy and positive Irish neutrality. And from this first quote we could also take inspiration in the struggle to save the environment:

“If Ireland is to be regenerated we must have internal unity; if the world is to be regenerated, we must have world-wide unity – not of government, but of brotherhood. To this great end every individual has a duty and that the end may not be missed we must continually turn for the correction of our philosophy to reflecting on the common origin of the human race, on the beauty of the world that is the heritage of all, our common hopes and fears, and in the greatest sense the mutual interests of the peoples of the earth.”

Seeing how Ireland was embroiled in the Great War by England, MacSwiney and the republicans of his generation wanted real independence:

“No-one is, I take it, so foolish as to suppose, being free, we would enter quarrels not our own. We should remain neutral. Our common sense would so dictate, our sense of right would so demand. The freedom of a nation carries with it the responsibility that it be no menace to the freedom of another nation. The freedom of all makes for the security of all.”

MacSwiney’s heroic hunger strike inspired millions of people across the world struggling to be free, especially those in India, Egypt and the many other British colonies in Africa and Asia. To those Irish nationalists who wanted to compromise with the Empire, and even profit from it, he had this message:

“For the Empire, as we know it, is a bad thing in itself, and we must not only get free of it and not be again trapped by it, but must rather give hope and encouragement to every nation fighting the same fight all the world over.”

MacSwiney was an optimist and believed the cause of the Irish Republic would prevail over the Empire. The struggle for the Republic has lasted longer than he envisaged but the Empire is down and down for good, the United Kingdom is shaking and Irish Unity is within our grasp. Towards the end of his hunger strike MacSwiney said to his friend Fr. Dominic:

“How we ought to pity these Sasanaigh. Their Empire is not only tottering but visibly falling. And once they are down they will never rise…”

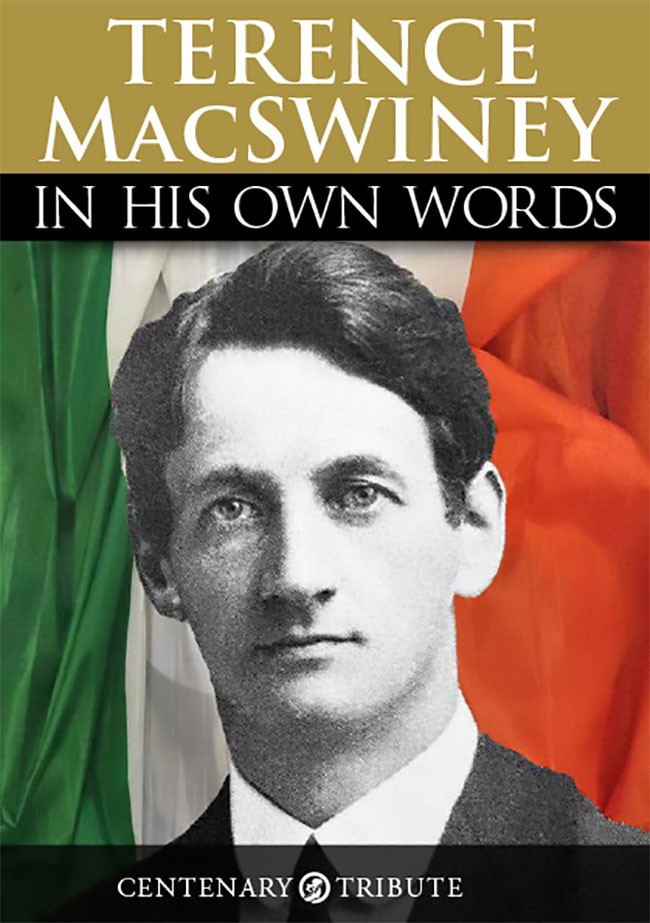

Mícheál Mac Donncha compiled and edited the booklet 'Terence MacSwiney - in his own words' which is available from the Sinn Féin Bookshop.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures