13 August 2020

Seán Russell and the IRA of the 1940s

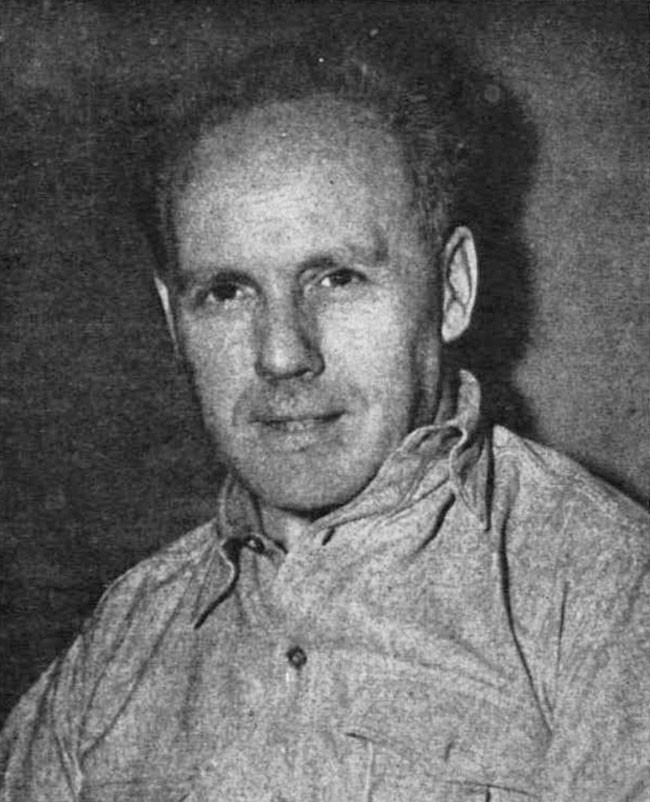

Eighty years ago on 14th August 1940 Seán Russell died on a German U-Boat and his body was committed to the sea. It was a journey that he began as a founder member of the Irish Volunteers and ended as IRA Chief of Staff attempting to return to Ireland from Germany.

Russell’s name was in the news again recently when, in the wake of attacks on statues in various countries, his statue in Fairview Park was dubbed controversial by Fine Gael Tánaiste Leo Varadkar and by a local Fine Gael Dublin City councillor. It was not the first time the Russell statue was used to attempt to score points at modern Sinn Féin, for party political point-scoring is what it was. Having got their media soundbites Fine Gael did not carry out their threat to seek the statue’s removal. However, other elements vandalised the monument, again not for the first time.

But who was Seán Russell and why the controversy? He was a Dubliner who joined the Irish Volunteers at their inception in 1913. He fought in 1916, was a senior member of the Dublin Brigade in the Black and Tan war, on IRA General Headquarters Staff as a very efficient Direct of Munitions in 1920-’21, and was with the Anti-Treaty IRA in the Civil War.

Russell was very much a military man, determined to arm and equip the IRA to resume the armed struggle against British occupation when the opportunity arose. In 1926 he was part of an unsuccessful IRA mission to Soviet Russia to acquire support. He was equally comfortable seeking help in the USA from Irish exiles. He played little part in the political battle of ideas in the IRA during the 1930s, disregarding ‘politics’ and focussing on military action.

The story of the IRA in the 1930s is a downward graph. Recovering throughout the ‘20s from the military defeat, executions and mass imprisonment of the Civil War, and the mass emigration of Republicans that followed, the organisation was revived and had a very large membership by 1932. In that year it assisted Fianna Fáil to defeat the Cumann na nGaedhal Government in the General Election. There was a honeymoon period with de Valera as both the IRA and Fianna Fáil confronted and marginalised the fascist Blueshirts. At the same time the left within the IRA leadership pressed for the movement to campaign on social and economic issues. The Chief of Staff Maurice Twomey tried to keep the Army together but in 1934 key figures left to form the Republican Congress. The Congress itself split and in 1936 de Valera turned on the IRA and banned it.

Military men like Russell saw all this as a vindication of their view that ‘politics’ should be left to the politicians. They were conscious also that when the IRA had embraced socialist policies in 1931 it had been widely condemned by the Catholic hierarchy and by many within its own support base, conservative Catholicism then being at its strongest in Ireland. In place of political ideology, policy and strategy, Russell and others adhered to the almost mystical notion that the seven surviving members of the Second Dáil Éireann constituted the legitimate government of the Republic. Russell linked up with Joe McGarrity and Clan na Gael, the Irish Republican organisation in the United States, which favoured a military campaign in the Six Counties and sabotage in Britain. Russell’s pursuit of this strategy in his tour of the USA, without the authorisation of the IRA Army Council, led to his expulsion from the IRA in 1937.

Russell fought back and gained control of the IRA leadership as Chief of Staff in 1938. That year saw the complete splintering of the big Movement that had been the IRA of the early 1930s. Frank Ryan and many of those who had departed to form Republican Congress had gone to Spain with the International Brigade, fighting for the Republic against Franco. Leaders like Tom Barry and Tomás Mac Curtáin who disagreed with Russell’s approach, resigned from the IRA leadership. Russell’s predecessor as Chief of Staff was Seán MacBride and he had resigned in 1937 believing that de Valera’s Constitution, adopted by referendum in the 26 Counties, provided a political path to Irish Unity and the restoration of the Republic. Maurice Twomey did not agree with Russell’s proposed campaign but remained in the IRA. To further complicate matters, numbers of IRA members who were left-wing in politics remained in the organisation under Russell.

Russell secured a declaration from the surviving Second Dáil members vesting their ‘authority’ in his Army Council. In January 1939 the IRA issued an ultimatum to the British government demanding the withdrawal of all British armed forces stationed in Ireland, and the bombing campaign in England commenced. The targets were low-level public facilities such as railway stations and telephone boxes. In a premature explosion in Coventry five civilians were killed. IRA Volunteers Peter Barnes and James McCormack were prosecuted for this, though they were not responsible for it, and were executed in February 1940.

Russell made contact with the Nazi government of Germany, through an agent sent to Ireland. James O’Donovan who had drawn up the plan for the bombing campaign in England, went to Germany as an IRA envoy. Republicans who disagreed with Russell became aware of these contacts and George Gilmore, a former leader of Republican Congress, openly condemned them. He described O’Donovan as ‘Fascist-minded’. O’Donovan was essentially a political exception in the IRA, though highly placed, his influence leading to material in the IRA’s journal ‘War News’ welcoming Hitler’s victories and even making anti-Semitic statements. But as Seán Cronin points out in ‘Frank Ryan the Search for the Republic’:

“On the matter of ideology, one must be cautious when dealing with the IRA….Many left-wingers did not follow Republican Congress into the wilderness in 1934 because their first loyalty, they felt, was to the IRA.”

Returning to the United States in April 1940, Russell hoped to garner further support for the campaign and to expand it to an armed effort in the Six Counties. However he was arrested and became the subject of much publicity with Clan na Gael demanding his release. He was released on bail and then went on the run. He was smuggled out of the United States to Europe with the help of the staunch socialist and Irish Republican Mike Quill, leader of the Transport Workers Union of America. He went by ship to Genoa and then to Berlin where he was welcomed by the German authorities and accommodated in a large house. There he remained during the summer of 1940 as France fell to the German onslaught. His main aim was to return to Ireland and to the IRA.

Was Russell a collaborator with the Nazis as his critics allege? He certainly did not see himself as such. He saw himself in the same position as Roger Casement during the First World War, seeking German aid for the effort to free Ireland with no strings attached. Based on interrogation of German intelligence agents even British intelligence concluded in 1946:

“Russell throughout his stay in Germany had shown considerable reticence towards the Germans and plainly did not regard himself as a German agent.”

Erwin Lahousen was a senior German intelligence officer who plotted to assassinate Hitler and went on to be a key witness for the prosecution at the Nuremburg war crimes trials. He said that Russell confided his views to him. He attributed these words to Russell:

“I am not a Nazi. I am an Irishman fighting for the independence of Ireland. The British have been our enemies for hundreds of years. They are the enemies of Germany today. If it suits Germany to give us help to achieve independence I am willing to accept it, but no more, and there must be no strings to the help.”

To many Republicans then, and certainly to most people today, these words would appear extremely naïve when dealing with one of the most vicious regimes that ever existed. And Russell was naïve and narrow-minded in his approach, certainly courageous and selfless but politically isolated and misguided. Many Republicans such as Tom Barry had come to realise that the only possible policy while de Valera maintained the neutrality of the Free State and, in 1940, faced possible invasion by both the British and the Nazis, was non-confrontation with the State and support for neutrality. This was also the view of Frank Ryan who in 1940 was in Germany, having been handed over to the Germans by the Franco regime following widespread pressure for the reprieve of his death sentence in a Spanish prison.

So it was in August 1940 that Russell and Ryan were reunited by German naval intelligence, the Abwehr, and boarded a German U-Boat to travel to Ireland. All this seems to have been very much a side-show for the Germans, while keeping their options open with regard to Ireland. Though Ryan and Russell had disagreed politically they had remained friends and perhaps if they had landed and seen the changed situation in Ireland the direction of the IRA during the remaining war years might have been different. But it was not to be. Russell took severely ill on board and on 14 August 1940 he died with Frank Ryan at his bedside.

In Ireland the IRA was at a very low ebb. When the English bombing campaign commenced in 1939 de Valera introduced the Offences Against the State Act and hundreds of Republicans were rounded up and interned without trial in the Curragh Camp in County Kildare. Many were tried before special courts. By the time of Russell’s death, two prisoners, Seán McNeela and Tony Darcy had died on hunger strike (April 1940) and Volunteer John Kavanagh had been shot dead by the Special Branch in Cork (August). A month later Volunteers Patrick McGrath and Thomas Harte, were executed in Mountjoy Prison. And the year ended with the death of Barney Casey, Republican prisoner shot dead in the Curragh by Free State military police.

The ruthlessness with which de Valera and his Justice Minister Gerry Boland pursued the IRA, and especially their treatment of prisoners, left a legacy of great bitterness. IRA members recalled that members of Dev’s party had not long previously been engaged in activities for which they were now jailing and executing Republicans. Gerry Boland had been on the IRA mission to Russia with Russell in 1926. The executed Patrick McGrath had been a personal friend of Dev and his wife Sinéad and was a 1916 veteran.

Due to censorship much of what was done in Dev’s prisons was only revealed after the war. This was one of the factors contributing to the rise of Clann na Poblachta, led by Seán MacBride, and the defeat of Fianna Fáil in the 1948 General Election.

The self-serving party political efforts to twist the memory of Seán Russell to attack Sinn Féin today are facile and unhistorical. With regard to the monument in Fairview Park they also ignore two key facts. Relatives of Seán Russell point out that as he was buried at sea this is their only memorial. And as the National Graves Association has pointed out, the monument does not only remember Seán Russell, it also names other IRA members of that period who lost their lives in the struggle for freedom. In the order they appear on the monument they are:

Tom Williams, executed Belfast Prison 1942

Patrick McGrath, executed Mountjoy Prison 1940

Thomas Harte, executed Mountjoy Prison1940

Paddy Dermody, shot by Special Branch 1942

Maurice O’Neill, executed Mountjoy Prison 1942

J.J. Reynolds, Charles McCafferty, John Kelly, killed in premature explosion, Castlefin 1938

Charlie Kerins, executed Mountjoy Prison 1944

Peter Barnes, James McCormack, executed Birmingham 1940

Seamus Burns, killed in action, Belfast 1944

George Plant, executed Portlaoise Prison 1942

Tony Darcy, Seán McNeela, died on hunger strike, Arbour Hill Prison, 1940

Seán McCaughey, died on hunger strike, Portlaoise Prison 1946

John Kavanagh, shot by Special Branch, Cork 1940

Richard Goss, executed Portlaoise Prison 1941

Gerard O’Callaghan, killed in action, Belfast 1942.

Sources and further reading

‘Frank Ryan the Search for the Republic’ by Seán Cronin

‘The IRA 1926-1936’ by Brian Hanley

‘Survivors’ by Uinseann MacEoin

‘The IRA in the Twilight Years’ by Uinseann MacEoin

‘Legion of the Rearguard’ by Conor Foley

‘The Lady at the Gate’ by Éamonn Mac Thomáis

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures