21 July 2020

Centenary of the Belfast Pogrom 1920

Remembering the Past

When the Partition of Ireland was first proposed in 1914 James Connolly said that such a scheme would mean “a carnival of reaction both North and South”. In the summer of 1920, as the British government unleashed the Black and Tans, and as it pushed forward legislation to partition the country, the carnival of reaction was seen in its full horror in the Six North-Eastern Counties that were to form the new state of ‘Northern Ireland’.

This reaction was both sectarian and political. Catholics were targeted because they were Catholics as Unionist political leaders and Protestant fundamentalists identified the Church of Rome as the threat to their way of life. Catholics were predominantly nationalist or republican and so they were seen as a political threat to the Union with Britain. In the Home Rule crisis of 1912-1914 Catholics had been widely targeted for sectarian attacks.

Sinn Féin had received a huge electoral mandate across Ireland in the 1918 General Election and in local elections in February and June 1920. Nationalists and republicans won control of Derry City Council and the County Councils of Fermanagh and Tyrone. The elections were held for the first time under the system of proportional representation, the results exposing the fact that even the Six Counties of ‘Northern Ireland’ were far from the ‘Loyal Ulster’ of Unionist propaganda. (They would see to this later when the new Unionist government abolished PR). The political nature of the reaction was also underlined by the fact that Protestant trade unionists and socialists were targeted as well as Catholics.

In Derry in June there were gun attacks on nationalists by the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force, as well as serious rioting, with 20 people killed. The storm intensified with the return to Ireland of Unionist leader Edward Carson. He had led opposition to Home Rule and was the key link between the Unionists in Ireland and the British Tory Party. He was a member of the British government during the First World War and was hailed by Unionists as a returning hero when he addressed the main Orange Order demonstration in Belfast on 12 July 1920. He poured petrol on the flames of fear about the rise of Sinn Féin. He said that if the British government did not protect them from “the machinations” of Sinn Féin then “we tell you we will take the matter into our own hands” and he threatened a revival of the UVF. Carson and fellow Unionist leader James Craig also whipped up fear of ‘Bolchevists’ as they warned Unionists of socialists and Sinn Féiners collaborating and seeking to recruit loyalist workers. In 1919 a strike in the shipyards had seen Protestant and Catholic workers united and no doubt this was in the minds of the Unionist leaders.

For the Catholic minority in Belfast the situation was now extremely dangerous. Unionist leaders were determined to consolidate their domination in order to firmly establish the ‘Northern Ireland’ state provided for in the forthcoming Government of Ireland Act. That domination rested on sectarian and political discrimination which ensured preferential treatment for Protestant workers, linked to their loyalty to the British connection. There was a cohort of Protestant unemployed workers who had been in the British Army during the war and could not find employment when they returned to Belfast. The same applied to many Catholics and there were both Protestant and Catholic ex-servicemen employed in the industries of Belfast. But the Ulster Unionist Labour Association played the sectarian card and demanded that preference be given to “loyal ex-service men and Protestant Unionists”.

In June RIC Divisional Commissioner for Munster Gerald Smyth had urged RIC men in Listowel, County Kerry to shoot suspects on sight and not to worry about the consequences. On 17 July Smyth was traced to the Cork County Club in Cork City by the IRA and shot dead. He was from Banbridge, County Down and his killing was used as an excuse by loyalists in that town to attack Catholic shops and homes and drive them out of workplaces. This was but a foretaste of what was to come in Belfast.

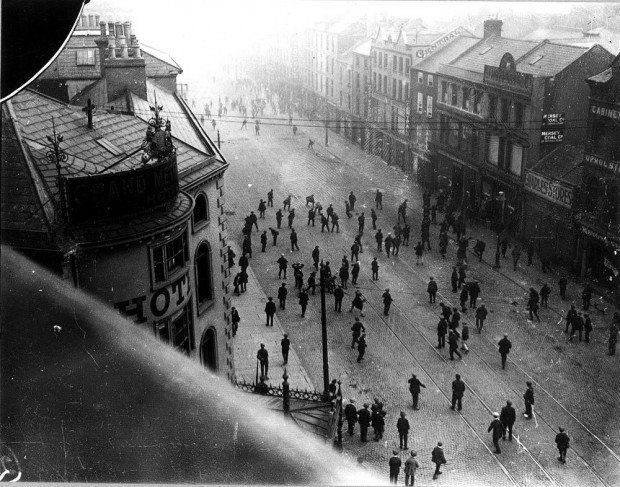

On 21 July posters summoned ‘Unionist and Protestant’ workers to a mass meeting in Belfast. The notices came from the Belfast Protestant Association and some 5,000 people assembled outside Workman Clark’s yard. The expulsion of ‘non-loyal’ workers from the shipyards and engineering works was demanded. Enflamed by loyalist rhetoric the crowd became an angry mob armed with revolvers, clubs and sledgehammers which they used to force their way into Harland and Wolff shipyard. They sought out Catholic workers and drove them from the yard; a small number of socialists and Protestant trade unionists were also expelled. Some workers had to jump into the River Lagan to escape. They were pelted with ‘Belfast confetti’ consisting of rivets and sharp metal shards. Workers were severely beaten and many were hospitalised.

In the following days the pogrom spread to other workplaces such as the Sirocco Works, Mackie’s Foundry and several linen mills. Expulsions continued for weeks and no exception was made for Catholics who had served in the British Army, some of them decorated for their services. Protestant workers not seen as sufficiently loyal were labelled ‘rotten Prods’, including sons of a Protestant yard worker forced from their work because their widowed father married a Catholic, as told to the TUC conference by Belfast socialist John Hanna.

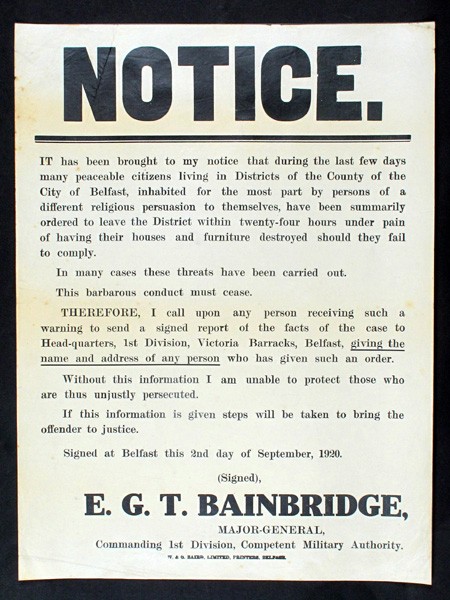

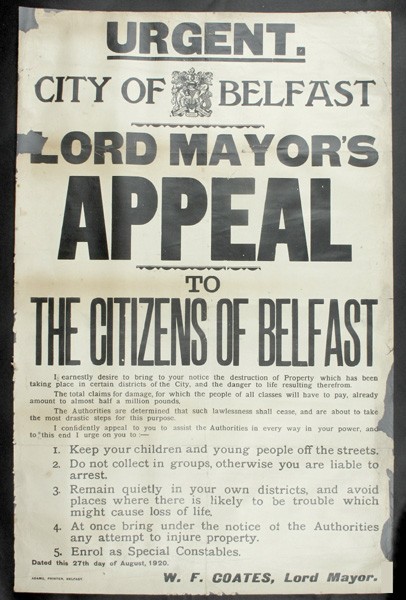

It has been estimated that 10,000 workers were expelled from their jobs, including several hundred women textile workers. But more was to come and the second element of the pogrom was the driving of Catholics from their homes. It began in East Belfast where many Catholic-owned public houses and ‘spirit groceries’ (grocery shops with alcohol licenses) were attacked and looted and the families who lived over them forced out. One estimate said that over 70 such premises were looted and destroyed. The Catholic St. Matthew’s Chapel and nearby convent in Short Strand were attacked and burned. Catholic families were expelled from their homes in Bombay Street between the Falls and Shankill Road, the first of many such expulsions. The British Army was deployed on the streets and several people were shot dead as the disturbances intensified.

On 1 September the Daily Mail commented:

“Now that 20 people have been killed and 400 Catholic families turned out of their homes, and £1 million worth of damage done, Belfast is beginning to come to its senses. Belfast is in its present plight and is faced with future trouble simply and solely because there has been an organised attempt to deprive Catholic men of their work, and to drive Catholic families from their homes.”

The IRA could do little to defend communities given the very vulnerable position of Catholics as a surrounded minority in the tightly packed streets of the city. In Dublin in August the Dáil Cabinet decided to start a boycott of Belfast goods as an act of solidarity and to try to pressure the Unionist leadership to stop the pogroms. Some republicans such as Constance Markievicz TD did not agree with the tactic, arguing that it would be counter-productive.

July 1920 was only the beginning of the pogrom. Attacks on Catholics and expulsions from jobs and homes continued through 1921 and into 1922. Nearly 500 people were killed in Belfast between July 1920 and July 1922. As the ‘Northern Ireland’ state came into being the Ulster Volunteer Force was revived and re-armed as a force of special constables – the B-Specials – of the new Royal Ulster Constabulary. Sectarian discrimination was to continue for decades.

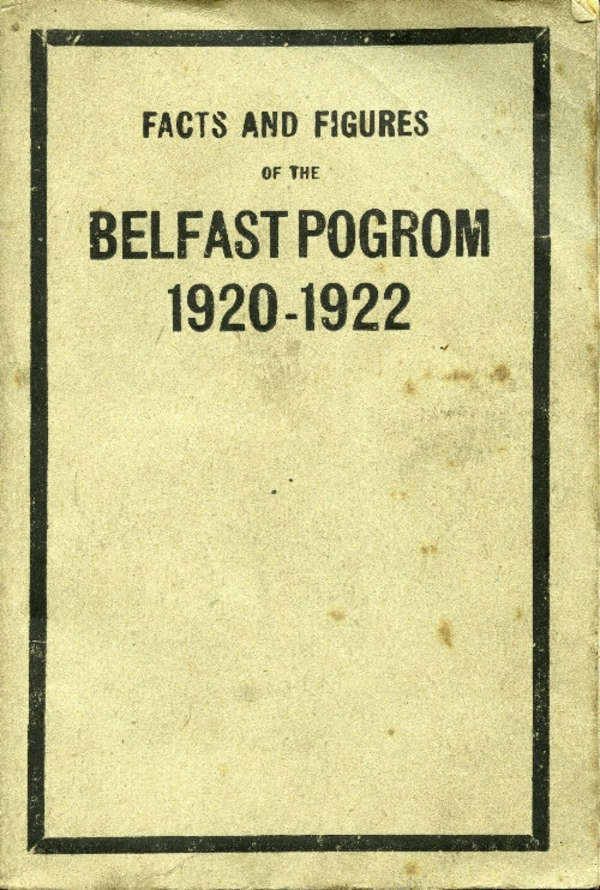

In 1922 a book entitled ‘Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922’ by G.B. Kenna (real name Fr. John Hassan) was published in Dublin. It detailed the full extent of the pogrom. Only a handful of the books were printed before, incredibly, in August 1922, the book was suppressed by the Free State Provisional Government in case it would assist the anti-Treaty IRA. It is poignant to note the dedication of the book:

“To the many Ulster Protestants who have always lived in peace and friendliness with their Catholic neighbours, this little book dealing with the acts of their misguided co-religionists is affectionately dedicated.”

Sources

‘Facts and Figures of the Belfast Pogrom 1920-1922’ by G.B. Kenna. Available online https://archive.org/details/factsfiguresofbe00kenn

‘The Start of the Belfast Pogrom, July 12th 1920’ in The Treason Felony Blog.

‘Belfast’s Unholy War’ by Alan F. Parkinson, Four Courts Press 2004.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures