3 July 2020

50th Anniversary of the Battle of St Matthews and the Falls Curfew

From An Phoblacht/Republican News, 30 June 2005

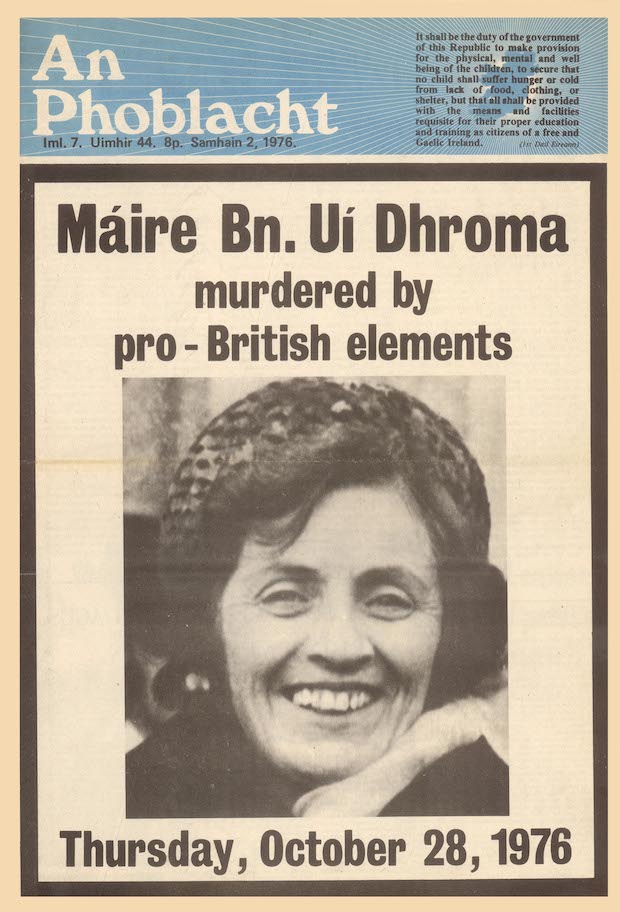

ADDRESSING a mass rally in west Belfast in 1975, then Sinn Féin Vice-President Máire Drumm spoke of the emergence of what she called “The risen people.” There had been resistance before, even armed resistance, but now “we have a risen people” and, as Máire told the crowd, “No one can beat a risen people.”

Republicans this summer remember the 35th anniversary of two seminal events which helped shape the current phase of struggle. Both events took place within weeks of each other in 1970.

The first witnessed the re-emergence of armed struggle but, unlike earlier campaigns, it was no longer symbolic but deeply rooted in the dynamic of struggle within Northern nationalist communities.

The second demonstrated the power of mass popular mobilisation to challenge repression, even military repression, by one of history’s most powerful imperial states.

• Sinn Féin Vice-President Máire Drumm

The Battle of St Matthew’s

THE SHORT STRAND is a small nationalist enclave within predominantly unionist east Belfast. It is situated in what was for decades one of the richest industrial areas in Ireland but years of systematic sectarian discrimination in the North ensured the Strand suffered some of the highest rates of long-term unemployment on the island.

While there is no doubt that unemployment has blighted the life chances of generations of Catholics born into the Strand, it has been the more immediate impact of overt unionist violence and the community’s resilience that has shaped its history. The Strand has suffered periodic pogroms that have spanned the imposition of partition to the present day.

Writing in the 1920s, a local observer commented:

“Who shall ever write the history of the isolated Catholic group in Ballymacarrett? The inhabitants are in peril, both indoors and out of doors. Their streets are constantly raked and tortured with gunfire from the mobs and from the Special police. One victim’s funeral follows another, sometimes three, four or five in a day. One wonders over and over again why they have not all become insane. And yet they live and face the future bravely, hopeful of a better time.”

And it was with the same courage and optimism that the people of Short Strand face the most recent sustained attacks against their community.

In 2002, the Strand, perversely, became victim of the current Peace Process as anti-Agreement unionists attempted to curtail political progress by creating circumstances in which they hoped the IRA would break its cessation.

The Strand endured months of sustained unionist paramilitary attack with the connivance of the PSNI and attempts by the British military to impose a curfew. In more recent months, the Strand has weathered attempts to criminalise the entire republican family in the wake of the brutal killing of Robert McCartney.

This month, republicans throughout Ireland will be joining with the people of Short Strand in remembering 'The Battle of St Matthew’s' and its significance in the last 35 years of struggle.

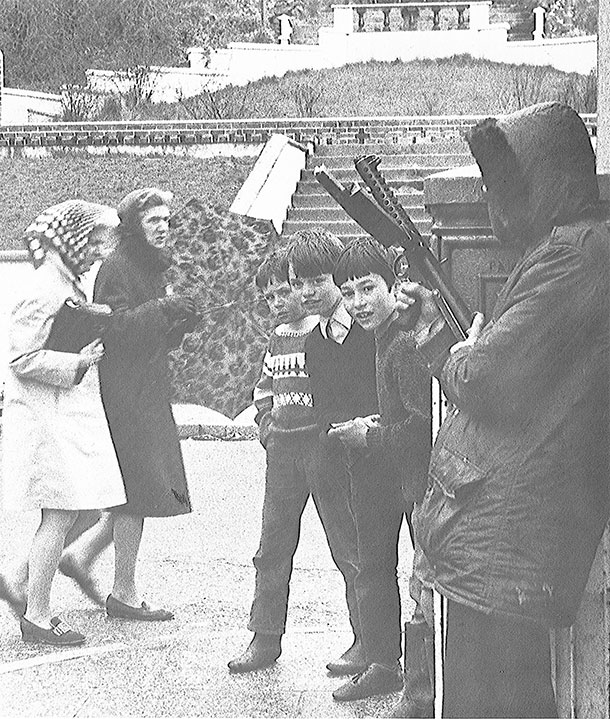

• Unionist paramilitaries tried to invade Short Strand

In the summer of 1970, the Strand came under one of the most determined attempts by unionist paramilitaries to invade the district.

There had already been a flood of Catholic refugees from outlying areas within east Belfast. Isolated families fled unionist attacks into the relative safety of the only sizeable nationalist enclave within the district. But their sanctuary was short lived when, on 27 June, armed unionist mobs attacked the Strand in the hopes of expelling the entire Catholic population from the east of the city.

St Matthew’s Chapel stands on the edge of Short Strand. It owes its location to the kindly offices of a Protestant benefactor, who donated the land in the late 19th century to enable local Catholics to build their own chapel. But the generosity of spirit that enabled its construction has stood in sharp contrast to the kind of bigotry that has seen the chapel become the repeated focus of anti-Catholic violence for the last 100 years.

During the pogroms of 1969, nationalist communities of Derry and North and west Belfast initially bore the brunt of attacks by the ‘B’ Specials and Orange mobs. But within months of the burning of Bombay Street, residents of the Short Strand were being taunted that they would be next. With the Orange marching season under way, contingency plans were drawn up to defend the Short Strand.

Despite repeated representations to the British authorities and the RUC to reroute Orange marches away from nationalist areas, on Saturday 27 June, an Orange parade was allowed to march down the Newtownards Road. Orangemen passing the Short Strand shouted sectarian abuse at residents and threatened that this would be their last night in east Belfast.

• IRA Volunteers fought an eight-hour battle to defend the area

But when the first unionist paramilitary shots rang out later that night, they were met with returned fire. A local IRA unit, supported by other Volunteers from the Belfast Brigade (and assisted by the Citizens' Defence League) fought an eight-hour battle in the grounds of St Matthew’s Chapel.

A small brick cottage in the chapel grounds – home to the sexton, his wife and six children – came under sustained petrol-bomb attack from the Orange mob. The children were dragged from their beds as the McGourty family fled under the cover of trees and bushes out of the chapel grounds.

The cottage was burnt to the ground as the family took refuge in the local primary school. It was here that 11-year-old Ignatius McGourty watched a fatally-wounded local man being carried into an adjacent classroom, together with injured IRA Volunteer, Billy McKee.

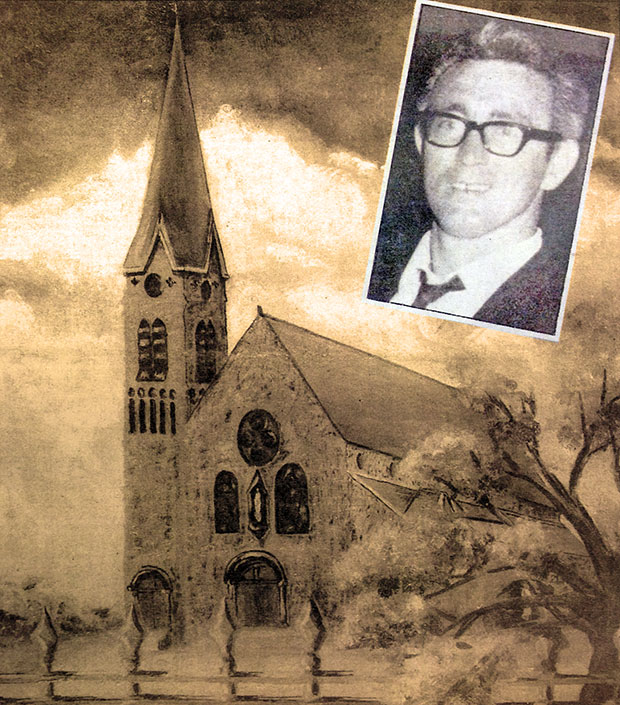

• A painting of St Matthew’s Chapel, Short Strand taken from An Phoblacht/Republican News June 1980, with Henry McIlhone who gave his life in defence of the area (inset)

Henry McIlhone had originally been from the Pound Loney, settling in the Short Strand after marrying a local woman. He was fatally wounded in the chapel grounds. A small metal cross at the side of the chapel, at the foot of a mature tree, marks the spot where he was shot. McIlhone was not a member of the IRA, he was 33 years of age when he died.

As dawn broke, the level of destruction visited on the area by the unionist mob became apparent. In an orgy of burning and looting, 20 Catholic-owned business premises on the outskirts of the Strand had been destroyed. But the district itself remained intact.

It had been more than just another sectarian attack. In June 1970, unionist mobs had intended to drive out the entire Catholic population of east Belfast in a Bombay Street type of scenario. Instead, the mob had been thwarted by a disciplined and valiant response in what was later recognised as the first major engagement of the IRA in defence of a nationalist area.

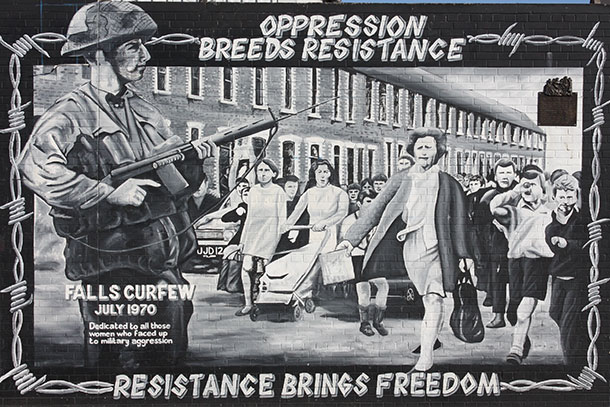

Breaking the Curfew

A few days later, another courageous stand was to be taken, this time in west Belfast, with the women of the city deploying an entirely different tactic to defend their area. This time the guns they were facing were not in the hands of a unionist mob but the equally hated British Army.

The resistance took the form of force of numbers rather than force of arms and, it has to be said, never in the history of any struggle have baby prams and shopping baskets been used to such great effect.

The IRA’s ability to defend the Short Strand had been a welcome reassurance to Northern nationalists but to the British Army it was viewed as an acute embarrassment. At a time when British military occupation was being justified on the grounds of protecting Catholics, the British Army had not only repeatedly ‘failed’ to do so, it had now been exposed by the success of a handful of sparsely-equipped Irish republicans.

To the recently-elected British Tory Government of the day, the repetition of such a scenario was unthinkable and within days the British Army was ordered to concede to unionist demands for mass raiding in nationalist areas to remove any weapons that might enable nationalist areas to defend themselves.

A raid for arms in the Lower Falls was the prelude to the imposition of a three-day curfew during which a number of civilians were killed. Hundreds of people were arrested while British Army raiding parties systematically wrecked home after home, street by street.

It began on the afternoon of 3 July, when the British Army arrived to raid a house in Balkan Street. A hostile crowd, mostly women, soon gathered and the hundreds of British soldiers deployed to facilitate the raiding were soon being jostled. The British Army retaliated with baton charges.

Local people, who had endured a number of terrifying unionist mob attacks the year before, were enraged at the sight of British soldiers removing weaponry from the house. “They’re taking our guns,” the cry went up and the crowd surged forward, whereupon the first of many CS gas canisters was fired by the British Army.

“Fenian bastards!” shouted an irate British soldier. “We’re giving your guns to the UVF,” he cried triumphantly, moments before he was pelted with bricks and bottles. The scene erupted into rioting.

Helicopters circling the area announced the imposition of a curfew. The British Army ordered people to go home under threat of being shot on sight.

As evening gave way to night, rioting gave way to engagement by the IRA.

“Around six o’clock, IRA patrols began to appear on the street, armed with rifles, handguns and grenades,” recalls Seán Stitt. “Everywhere, young children were being gathered up by their parents and older men and women withdrew from the front. The stage was being set for the biggest battle for years between the IRA and British Army.”

The battle raged all night but by dawn it was clear that, instead of withdrawing, an enraged British Army was determined to punish the entire community with punitive door-to-door raiding. By Saturday, British soldiers had given up any pretence they were actually searching for anything and simply ransacked homes, smashing property and beating residents.

The curfew continued throughout Saturday and Sunday morning, with just an hour allotted by the occupying army to allow families to collect necessities from local grocery stores, but with insufficient food supplies within the area, many families went hungry.

With news that four people had already been killed by the British Army and rumours of further atrocities, the mood in the Lower Falls became subdued. Meanwhile, the British Army, believing itself to be victorious, subjected the population to sectarian abuse and death threats.

And then news began to filter through the area that thousands of people, mostly women, were marching towards the area in a determined attempt to break the curfew.

In a mass show of defiance against the British Army and of solidarity with the people of the Lower Falls, thousands of women, many pushing prams loaded with bread, milk and eggs, broke the curfew. Barriers were swept aside, British soldiers and their machine-gun posts were overwhelmed by the crowd, forcing British Army commanders to order their men back to barracks.

The curfew was over and the British Army had been exposed as an army of occupation. They would never again be looked upon as anything other by Northern nationalists.

The organiser of this daring act of mass civil disobedience was Máire Drumm. During the violent pogroms of August 1969, Máire had emerged as an organiser, working tirelessly to rehouse families who had been forced to flee from their homes by unionist mobs.

A lifelong republican and an outspoken opponent of British occupation, Máire soon became a bête noir of the British media. The British campaign of vilification ended with her murder in the Mater Hospital in 1976. At her funeral, a comrade answered her critics:

“She was a fighter. She fought for what she believed in. She did not crawl. She asked for no quarter and she gave none. If she was extreme, it was because she was extremely right, extremely committed and did not believe in compromise.”

The breaking of the Falls Curfew was one of the first of many times women from the nationalist communities challenged British occupation through mass street mobilisation. Of course, women have always played their part in the IRA and Sinn Féin but throughout the current phase of the struggle it has been in the organisation of and participation in street protests that women have made their most visible contribution.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures