26 March 2020 Edition

Our responsibility is to establish the Republic envisioned in the 1916 Proclamation

The Sinn Féin and IRA splits of 1970

• The pogroms changed everything, demanding unity of purpose and clarity and resoluteness of action

1969 was a watershed year for the North and for republicans. It began with a People’s Democracy march being attacked by B-Specials and Unionists at Burntollet, outside Derry. That was in January. In July a Catholic pensioner, Francis McCloskey, was killed in Dungiven and Samuel Devenny died from injuries he received when batoned in his home in Derry in April by the RUC. In the following months there were further attacks on Catholic neighbourhoods. These included attacks by the Shankill Defence Association, supported by the RUC and B-Specials, against Unity Flats and Catholic families in the Crumlin Road area. Young activists like me spent a lot of our time assisting people in these communities.

The situation deteriorated further when the Unionist regime at Stormont allowed the annual Apprentice Boys parade to go ahead in Derry. This decision resulted in the Battle of the Bogside. In Belfast the Civil Rights Association agreed to organise demonstrations against the actions of the state police across the North.

In Dublin, three cabinet ministers proposed that the Irish army cross the border and seize Derry, Newry and other areas of majority Catholic population. On August 13th the then Taoiseach Jack Lynch went on television to announce that “the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse”. They did.

Widespread pogroms against Catholic areas then took place in Belfast. Unionist mobs, including many members of the B Specials, armed with rifles, revolvers and sub-machine guns petrol bombed dozens of Catholic houses in the Falls and Clonard areas.

The RUC opened fire with heavy calibre Browning machine guns from Shorland armoured cars. Very quickly the Clonard area and the Falls Road was turned into a war zone. Catholic families fled their homes across Belfast.

Over the two days of the 14th and 15th of August eight civilians were killed. Seven – including two children - died in Belfast and one person was shot dead by the B-Specials in Armagh. In two months - August and September – 3,500 families fled their homes in Belfast. 85 per cent of them were Catholic.

This was the background to the tensions that emerged within republicanism. The IRA leadership had failed to recognise the dangers that existed. Local IRA units did defend communities to the best of their ability but the authority of the IRA leadership was being significantly questioned.

Behind the barricades that now sealed off large parts of nationalist Belfast older republicans, who had drifted from the movement after the 50’s campaign, began to come back. Younger people flocked to join the IRA in order to protect their families and districts. Side by side with this there was a rapid growth in people joining Sinn Féin.

The failures of the IRA leadership were compounded by its inability to grasp the emerging opportunities for change and for advancing nationalist and republican demands on civil rights. It was unable or unwilling to provide a leadership capable of unifying or encouraging the maximum unity of progressives, anti-imperialists, liberals, socialists, republicans and nationalists.

• August 1969 became a watershed moment in our history. The response of republicans was to split. Movements rarely split of their own accord. Leaderships split first

However important the lack of defensive weapons, the primary problem was the lack of political awareness, vision, energy, or acumen needed to provide leadership based on the objective reality and conditions at a historic point of crisis. Sometimes leaderships work within their own little bubble, detached from their base and the people. This is fatal.

Some of those older republicans who came back, like Billy McKee, also lacked a strategic or a political view of events or of the future route of struggle. They coalesced with Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Seán Mac Stíofán and others. For some time before 1969 they had resisted the directions being set out by the leadership.

Their views were articulated by veteran Belfast republican Jimmy Steele at the re-interment of Barnes and McCormack in July 1969. Barnes and McCormack had been hanged in England in February 1940. Jimmy Steele criticised the republican leadership and its political direction in his oration. Those who supported his position had one thing in common with the Goulding leadership; both failed to see the need to stay united.

I attended the re-interment. I did not realise the full impact of Jimmy Steele’s remarks except to note to myself that it was unusual for a republican to criticise the leadership in such a public way.

These internal difficulties were compounded by the Dublin leadership’s decision to act on the recommendations of the Commission which it had been mandated to establish at a previous Ard Fheis. The Commission made recommendations about future direction, including the establishment of a National Liberation Front, the ending of abstentionism and the development of electoral politics.

However, all of this had been initiated some time before the August pogroms. The pogroms changed everything, demanding unity of purpose and clarity and resoluteness of action. At the very least, the leadership should have recognised the need for urgent new priorities and suspended its pursuance of the new departure in republican strategy until a more settled time. To come before the membership, as it did in the autumn of 1969, with findings recommending the ending of abstentionism and the development of a wider and demilitarised, broadly anti-imperialist movement was irresponsible.

These proposals were not only anathema to older activists, who had returned, but to newer, younger activists. It also, and more importantly, showed a fixation with these ideas and a blindness to the real needs of the moment. The smaller, mostly younger cohort of members who had been active in the years before ’69, in Belfast at any rate, were uncomfortable that some of those who were most critical, particularly of the Army’s lack of capacity during the pogroms, were themselves inactive in the build up to August. Some of these older elements may also have had personal or historical differences of opinion with the people in the leadership. We younger activists also had differences with the Dublin leadership but we did not have the experience or authority to have any real influence on internal developments. So August 1969 became a watershed moment in our history. The response of republicans was to split. Movements rarely split of their own accord. Leaderships split first.

Belfast republicans passed a vote of no confidence in the Dublin leadership and suspended its contact with it.

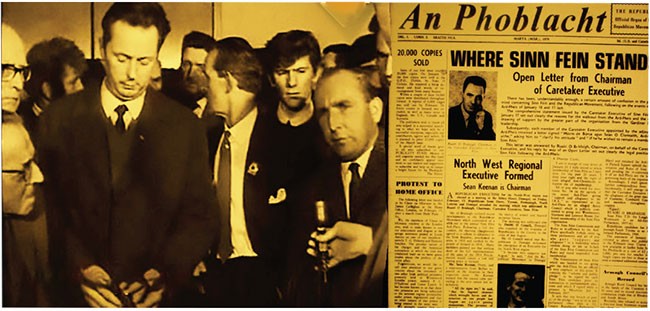

• Seán Mac Stíofáin with delegates who walked out of the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in January 1970, including (bottom left) 1916 veteran Joe Clarke; the monthly An Phoblacht was established in February.

Despite this, in December at an IRA army convention, the Dublin leadership pressed ahead with its proposals. There was a walk-out. For many of those who left the issue was not only about abstentionism but what it had come to represent: a leadership with a wrong set of priorities which had led the IRA, as they saw it, into ‘ignominy’ in August. The split was now out in the open. A provisional army council of the IRA was established.

The Sinn Féin Ard Fheis was held in January 1970. Before this, the leadership manoeuvred to prevent delegates who were critical of the IRA leadership’s direction from attending the Ard Fheis. I attended and spoke at the pre-Ard Fheis Belfast meeting. I was on cordial terms with those assembled, mostly younger activists who had been busy on housing and civil rights campaigns.

But when I arrived at the Ard Fheis in what was then the Intercontinental Hotel (now the Ballsbridge Hotel) in Dublin, I was blocked. I was a delegate from my local cumann but I was told that I didn’t have proper accreditation. I went off to an anti-apartheid protest instead.

At the Ard Fheis the Dublin leadership’s position was defeated. It failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority for a change of the Sinn Féin constitution. However, the leadership then stupidly brought forward a motion expressing confidence in the army leadership. That same leadership had just split. There was another walkout and the split was complete.

Hindsight is a great person to have at the table. Over the years I have learned that some activists are splitters. The primary objective of the national struggle in Ireland is to win national freedom by ending the Union and Partition. All republicans should unite around that central objective. We should not be distracted by other issues, no matter how important these may be in their own right. Unfortunately some allow this to happen. National independence or liberation movements which split usually do so on social or economic issues.

James Connolly had the best formula. He said that the national and social are opposite sides of the one coin. That should be our mantra. It makes sense. It marks Sinn Féin out from other parties on the left. Socialists should be the best republicans. All of us need to be uniters. We should be guided by democratically agreed strategic objectives. The reconquest of Ireland by the people of Ireland is our aim. It is all about the people. Empowered, connected, organised people with a stake in the struggle. Conspiratorial manoeuvrings by cliques, Stalinist factions or militaristic fantasists have no place in this.

In May 2000 at an event in Cork a Workers’ Party TD, the late Joe Sherlock, a decent man, congratulated me. He said we had done what they had failed to do.

Last week I was at Tommy Smith’s funeral in Dublin, another decent man, an outstanding republican and patron of the arts. At that funeral a former prominent ‘Official’ congratulated me on Sinn Féin’s General Election result. “Ye succeeded in doing what we tried but failed miserably to do.”

I have long believed that the split represented a significant set-back for the struggle. The ‘feuding’ which followed was reprehensible and totally wrong. Advancing republican objectives is best done with a cohesive, united party pulling in the same direction. The recent election results, North and South, have shown there is a growing appetite for republican politics across the island. Support for Irish Unity is also growing. Our responsibility, our historic task, is to end partition, achieve national self-determination and unity and to establish the Republic envisioned in the 1916 Proclamation and the Democratic Programme of the First Dáil.

• Gerry Adams is a former Sinn Féin president, MP and TD.