12 April 2020

The 1916 Rising outside Dublin

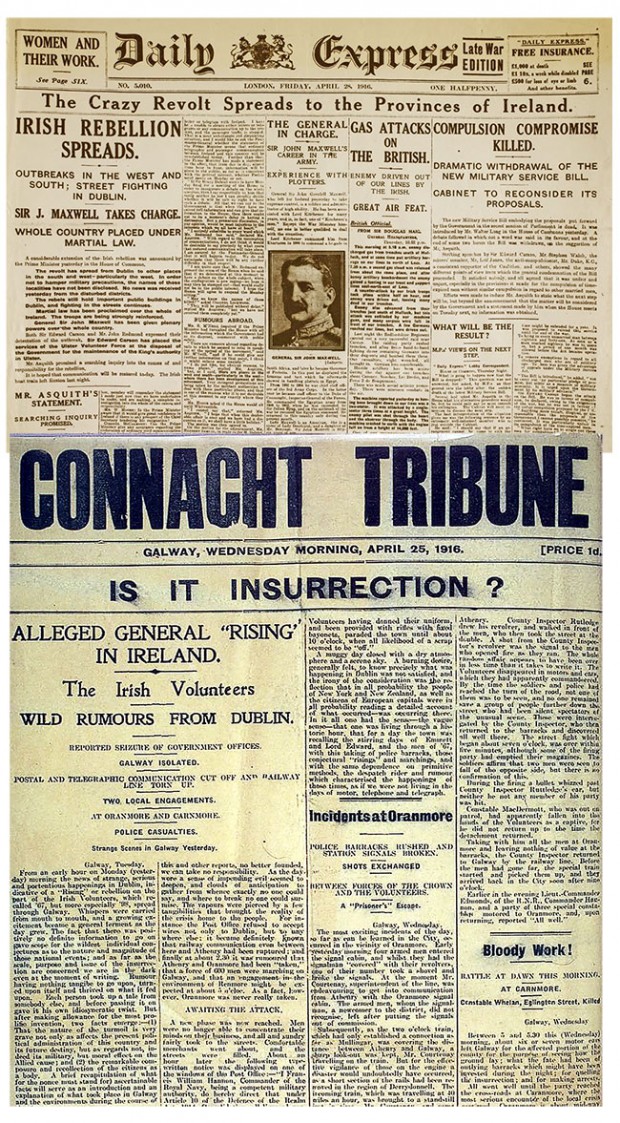

WHILE VOLUNTEERS from all across the country fought in Dublin during Easter Week, the plans for the Easter Rising envisaged weapons from Germany being distributed to units across Ireland. The capture of the Aud scuppered these plans and, with mass confusion caused by Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order on Easter Sunday, most parts of the country remained quiet. In Tyrone, Limerick, Kerry and Cork City, large numbers of Volunteers mobilised but then stood down amid the confusion. There were a number of exceptions though.

County Laois

The first military action of the Rising is believed to have taken place in County Laois where, the night before the Rising began, Volunteers destroyed a railway track at Clonadadoran, between Abbyleix and Portlaoise, to prevent British military reinforcements reaching Dublin via Wexford.

The Carlow–Kildare railway line was also bombed by the Laois Volunteers while Volunteer John Frawley carried out a raid on Wolfhill police barracks by himself! He was later taken prisoner.

County Louth

As with many of the other Volunteer units, the Louth Volunteers were in a state of confusion following the countermanding orders.

They had left Dundalk and marched towards Tara on Easter Sunday but began to return home on Sunday night. At Lurgan Green, a confirmation despatch finally came through from Pearse to the 28 Volunteers: “Dublin is in arms. You will carry out your original instructions.” At this point, the commander, Dan Hannigan, informed the citizens that a Republic had been declared. He called on the dozen Royal Irish Constabulary officers there to surrender, which they did, and the Volunteers then arrested a number of British officers passing in two cars.

In Castlebellingham, the force captured a further 10 RIC men and a British Army lieutenant who was passing in a car. As they were leaving Castlebellingham, the RIC and Lieutenant Dunville were ordered to remain at the railings where they had been coralled. Dunville made a grab for a rifle from one of the Volunteers and Volunteer Seán McEntee opened fire, killing Constable Charles McGee and wounding Dunville. McEntee would then travel to Dublin where he fought in the GPO. The Louth unit moved towards Dublin, taking over Tyrrellstown House near Blanchardstown. They then arranged to link up with Thomas Ashe's Fingal Battalion near Turvey but, by the time they got there, Ashe's force had surrendered.

• Enniscorthy Volunteers during the Rising on 1 May. Front row: Séamus Rafter, Robert Brennan, Séamus Doyle, Seán R. Etchingham. Back row: Una Brennan, Michael de Lacy, Eileen Hegarty. (Capuchin Annual, 1966)

County Wexford

On the Tuesday of Easter Week, the Enniscorthy and Ferns companies of the Volunteers were ready for a fight and on Wednesday decided they would try to hold the town. The Tricolour was hoisted over Enniscorthy's Athenaeum Theatre, which served as the headquarters of the Volunteers. A gun-battle then broke out between the Volunteers and the RIC located in the barracks during which an RIC man was shot and injured. The Volunteers did not attempt to storm the barracks and instead planned on forcing them to surrender in order to capture their arms and ammunition which were desperately needed by the rebels.

On Saturday, the town was still held by the Republic but news began to filter through of the surrender in Dublin. The Enniscorthy fighters refused to surrender until their officers, Seumus Ó Dubhghaill and Seán Etchingham, were escorted to Arbour Hill in Dublin, where they met with Pádraig Pearse. He confirmed the surrender order in person and told them to lay down their arms but to hide them rather than hand them over to the British. “They will be needed later,” he whispered to Ó Dubhghaill.

County Galway

Eoin MacNeill's order canceling the mobilisation had a disastrous effect on Galway. The Volunteers were very strong in the county and the countermanding orders ruined any chance they had of a surprise assault. When news reached Liam Mellows of the Rising in Dublin, he ordered a general mobilisation and almost 1,000 Volunteers reported for duty and a HQ was established near Kilineen.

Despite the large number of fighters, the rebels possessed only 25 rifles and instead relied heavily on poorer short-range weapons consisting of 300 shotguns, 60 revolvers and 60 pikes. In Oranmore, a unit of Volunteers captured six RIC officers. One officer, Sergeant Healy, evaded capture and barricaded himself in a building opposite the barracks, putting up stiff resistance. During the clash, RIC reinforcements arrived and forced the Volunteers to withdraw to Athenry. An attempted attack by the RIC on the town on Wednesday was met by heavy resistance.

The number of rebels in Galway clearly panicked British forces. In one incident, on Wednesday, the British warship HMS Laburnum shelled the Galway coastline after claiming it saw a convoy of rebel vehicles approaching Galway City.

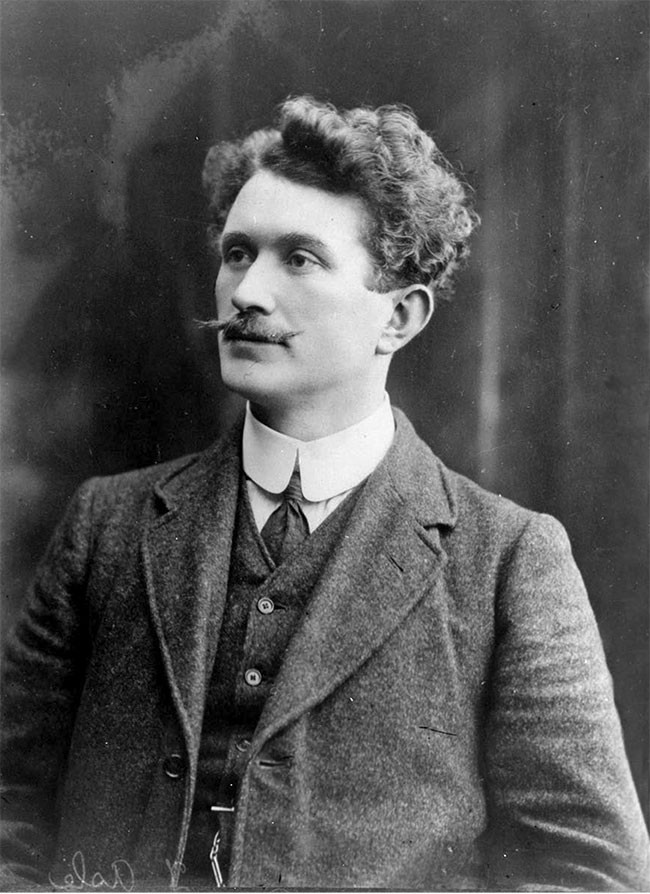

• Liam Mellows

Michael Newell, one of the rebels, recalls an engagement between the Volunteers and an RIC convoy approaching Carnmore:

“The cars proceeded to about one hundred yards from our position and then halted. The enemy advanced on foot on our position, firing all the time. Captain Molloy ordered us to open fire, which we did, but the enemy fire was so intense and the bullets striking the top of the walls, we were compelled to keep down, and we were only able to take an occasional shot. RIC Constable Whelan shouted, 'Surrender, boys, I know ye all!' Whelan was shot dead and the district inspector fell also and lay motionless on the ground. The enemy then made an attempt to outflank our position but were beaten back. The enemy then retreated and continued to fire until well out of range of our shotguns. They got back into the cars and went in the direction of Oranmore.”

By Thursday, the rebels, both Volunteers and Cumann na mBan, realised they could only offer token resistance but decided to continue fighting. By Friday, almost 1,000 additional British troops were pouring into Galway county. The rebels planned a retreat to Clare just as news was coming through that heavy artillery was being used on Irish positions in Dublin. It was finally decided that, in the face of such overwhelming odds, the force would disband and the leaders go on the run.

County Cork

While there were large mobilisations of Volunteers in Cork and Kerry, the countermanding order led to confusion and rows, paralysing the organisation from carrying out any operations.

In Cork, the only shots fired by the rebels were those of the Kent brothers in Fermoy, with Thomas Kent becoming the only rebel leader to be executed outside of Dublin in the immediate aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising. (Roger Casement, captured in Kerry, would be hanged in London's Pentonville Prison, England, three months later.)

The Kent family, from Castlelyons, east Cork, had long been active in agitation against British rule. The four Kent brothers formed the core of the local Irish Volunteer force in the area. They had planned to take part in the Easter Rising and had departed for Dublin but, on hearing Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order, turned back on 1 May and headed home. Early the next morning, a force of Royal Irish Constabulary surrounded the family's Bawnard House home.

• Cork – The arrest of Thomas and William Kent, later court-martialed, with Thomas sentenced to death by firing squad and William acquitted

The RIC demanded the surrender of arms and wanted to “arrest members of the family who are identified with the Sinn Féin movement”. The response from the family, including their 84-year-old mother Mary, was defiant: “We are soldiers of the Irish Republic and there is no surrender.” A fierce gun battle ensued during which David Kent was injured, shot in the side and losing two fingers; the RIC Head Constable, W. M. Rowe, was killed and others injured. British soldiers arrived to reinforce the RIC and the battle raged for over three hours.

A report from the time noted:

“The old lady loaded rifles and shotguns while her sons blazed away.”

This was confirmed by William Kent in a statement to the Bureau of Military History years later where he noted:

“Our mother, then over 80 years of age, dressed herself, and all during the ensuing fight assisted by loading weapons and with words of encouragement.”

The Kents resisted until they ran out of ammunition and the house was severely damaged.

When they surrendered, British soldiers lined the brothers up against the wall and were preparing to shoot them only for the intervention of a medical officer.

Richard Kent attempted to escape and was shot and fatally injured. Thomas and William Kent were court-martialed, with Thomas sentenced to death and William acquitted.

Thomas was executed by a British naval detachment on 9 May at Victoria Barracks (now Cork City Prison) and buried within its walls.

County Meath

The most significant actions of Easter Week outside of Dublin came in County Meath.

Volunteers of the Fingal Battalion had mobilised on Easter Sunday but stood down following Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order. Orders from Pádraig Pearse arrived the next morning ordering the battalion to “strike at 1pm”. Twenty men were sent to Dublin to join the fighting while the rest were ordered to create a diversion outside the city. Throughout the week, a 45-strong column engaged in lightning raids on RIC barracks in Donabate, Swords and Garristown, and bombing attacks on infrastructure in the area.

The unit, under the command of Thomas Ashe, planned to bomb the Great Western Railway line at Batterstown in order to disrupt the ability of British forces to send reinforcements to Dublin. Before it could be destroyed, the RIC barracks at Ashtown, which scouts reported as being heavily defended, needed to be destroyed.

• Thomas Ashe

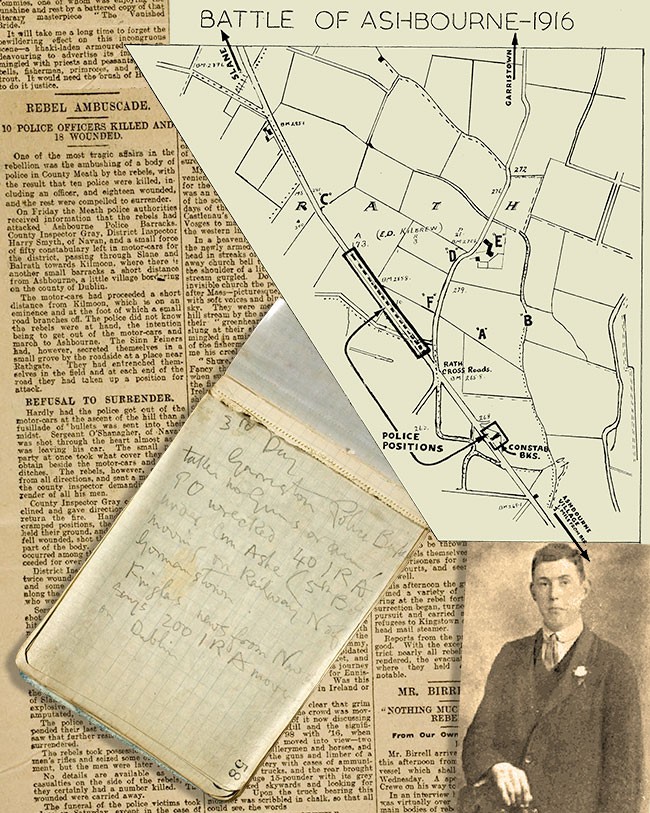

On the Friday of Easter Week, the Volunteer unit moved towards the barracks. An advance unit of the Volunteers surprised two RIC officers who were in the process of erecting a barricade across the main road in front of the barracks and took them prisoner. Volunteers moved quickly to then surround the barracks. Once this was done, Commandant Thomas Ashe marched out onto the main road in front of the barracks and demanded those inside surrender. The RIC replied by opening fire and Ashe was forced to dive for cover.

The Volunteers responded with almost 30 minutes of continuous fire, raking the building with bullets and splintering the woodwork. The RIC inside fired back, moving from window to window. The Volunteers tossed two homemade grenades at the barracks but could not bring down the heavily-reinforced barracks door.

Nevertheless, the sound of grenades exploding panicked the defending RIC men, who were running low on ammunition, and shortly afterwards they raised a white flag from one of the windows. Before they could march out to surrender, however, a column of 24 vehicles of police reinforcements – around 70 men – arrived on the scene. The convoy was under the command of RIC District Inspector Harry Smyth, a former British soldier from Herefordshire in England.

Many of the Volunteers became nervous at the sight of such a huge number of reinforcements but Thomas Ashe quickly took control of the situation:

“He assured us that the police had no chance of success,” recalled Volunteer Joseph Lawless. “That we were going to rout or capture the entire force. His words had the immediate effect of inspiring confidence and making us feel ashamed of our previous apprehensiveness.”

• Map of the Battle of Ashbourne taken from The Capuchin Annual, 1966; 21-year-old Volunteer John Crenigan was killed during thebattle; Joseph’s Plunkett notebook from the GPO stating ‘Police Barracks taken. No guns or arms! Post Office wrecked. 40 IRA under Commandant Ashe’; Daily Mail report on the action at Ashbourne

While the Volunteers were surprised by the reinforcements, the police did not expect to meet such resistance and had halted their column and dived for cover once they came under fire – with County Inspector Alexander Gray hit in the opening salvo. A number had been killed and most were now pinned down in ditches. The Volunteers, though poorly armed, decided to take advantage of this and ordered a full-strength attack on the RIC positions. Disaster almost struck at one point when Volunteer forces opened fire on some of their own reinforcements who were arriving from Borranstown. In the incident, Colonel Frank Lawless's men had exchanged fire with a unit which was being led by his own father, Joe – thankfully, nobody was hit.

At the crossroads, section leader Volunteer Richard Mulcahy shouted to the surrounded RIC force: “Will you surrender? By God if you don't we will give you a dog's death.” But the RIC continued firing back, a number taking cover beneath the police cars. Mulcahy then ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge the RIC. On seeing this, many RIC threw down their weapons and surrendered – others fled to seek shelter in a nearby cottage. Other Volunteer units then broke cover and rushed the RIC ranks. During the attack, 21-year-old Volunteer John Crenigan was shot dead by Inspector Harry Smyth. As Smyth fired his revolver, he in turn was shot in the head by Volunteer Frank Lawless with a Mauser rifle. On witnessing the death of their commanding officer, the remaining RIC officers surrendered.

The battle had raged for almost four hours. The 15 police in the barracks also surrendered.

After the battle, Thomas Ashe informed the RIC prisoners that if they ever attempted to take up arms against the Irish Republic again they would be shot dead. He then released them. It is notable that even media outlets hostile to the rebels commended their treatment of prisoners. The Leitrim Observer, even while describing the rebels as “murderous”, added, “They, however, behaved very well towards their prisoners,” noting they provided food, water and medical assistance to them.

When the battle ended, eight RIC men were dead and 15 wounded while the Volunteers lost one man and a further six wounded. One of these men, Volunteer Thomas Rafferty from Lusk, would die from his wounds the next day. Two civilians, John Carroll and Jeremiah Hogan, who accidentally drove into the battle zone, were killed, as were a number of civilian drivers employed by the RIC. RIC County Inspector Alexander Gray also succumbed to his injuries two weeks later.

In attempting to explain their defeat at Ashbourne, the British and their press made outlandish claims that they had been ambushed by more than 400 rebels.

Other incidents

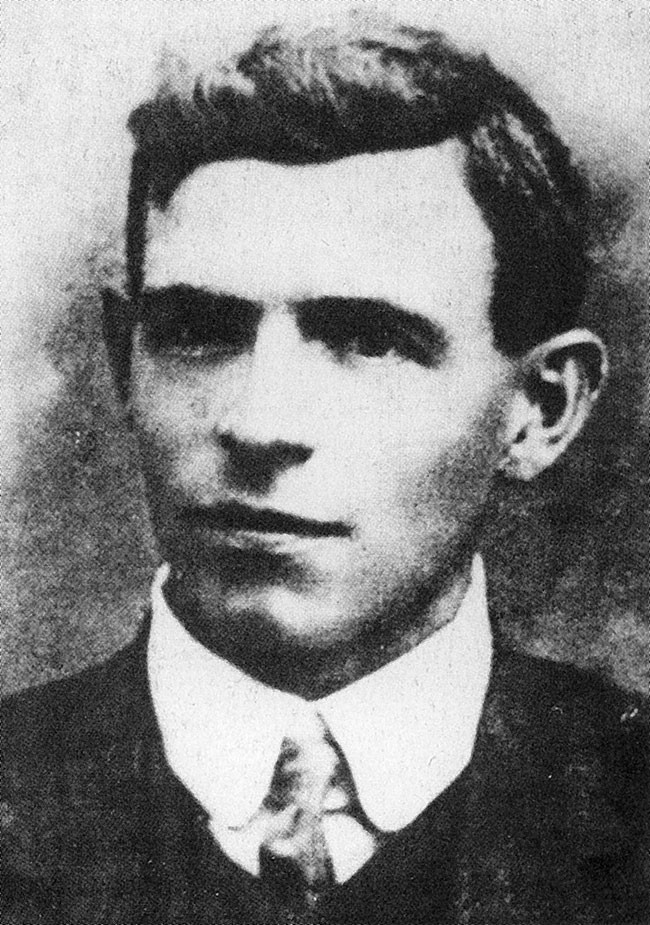

• Michael O’Callaghan

Tipperary

There were other small scale incidents elsewhere including in Tipperary town were two RIC officers attempted to arrest IRB and Irish Volunteers member Michael O'Callaghan. O'Callaghan shot and fatally wounded both before escaping and fleeing to New York.

Belfast, Derry and Tyrone

Volunteers in Belfast, Derry and Tyrone marched as far as Coalisland in Tyrone, planning to link up with units in the West but the confusion saw them return home.

CORK CITY

In Cork City, an agreement was reached between the Volunteers and the RIC that Volunteers would surrender their arms and no arrests would be made. However, this was reneged on by the RIC and Tomás Mac Curtain and ten other Volunteers were arrested.

• Tomás Mac Curtain

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures