16 December 2019

The Battle for Survival of Rural Ireland

No One Shouted Stop: Death of an Irish Town was the 1988 title of Irish Times journalist John Healy’s seminal book dealing with the decline of Charlestown, a town in East Mayo familiar to anyone who has travelled the N17 from Sligo to Galway. The book was particularly concerned with this case study of social and economic degeneration in the west, but also the destructive impact of emigration on the vitality of rural communities more generally.

Anyone who lives in rural Ireland will tell you that the sentiment expressed here can be felt in towns and villages all over the country, but it is particularly pronounced in the west.

The Democratic Programme of the first Dáil provided the ideological basis for a truly all-Ireland and radical egalitarian agenda that would deal with the legacy of British rule. Since partition, however, the economic development of the 26 counties has been dictated by successive conservative and sycophantic administrations that quickly abandoned the political aspirations of the revolutionary period when in power. The past half century or so has been particularly marred by a post-colonial and reactionary approach to economic policy.

The nature of industrial development over the past 50 years, but particularly since the 1980s has only served to widen the gap in this state between east and west, urban and rural.

An ERSI report published in January 2018 attests to this. It argues that excessive concentration of economic activity in Dublin is having a negative effect on the economic performance of the state as a whole. It also predicts that, without intervention, Dublin itself will actually increase its share of jobs between now and 2040, widening the gap further.

This spatial concentration of economic activity in the urban east coincides with a recent intensification of stripping back funding for public services and transferring decision-making powers further away from rural communities. People have witnessed post offices, Garda stations, schools and A&E units close in their communities. Many public service responsibilities once under the control of the local authorities such as waste collection, general maintenance, water services and aspects of planning, have been centralised, privatised or both.

Central government in the 26 counties now accounts for a higher proportion of total government spending than almost any other EU country. Economist Michael Taft has shown how in the EU-15, central government constitutes approximately 54% of all government spending while in Ireland it accounts for 95%.

Funding from central government to local authorities in 2018 totalled around €1.7 billion. This compares with €5.8 billion in 2008 – a 71% drop in 10 years. From 2011–2018, five local authorities have had funding cuts of over 50% - Roscommon, Donegal, Galway, Sligo and Offaly.

This reduction has resulted in extremely poor road surfaces, an inability to meet critical housing and maintenance requirements as well as an inability to invest in community services such as men’s sheds, youth services and care for the elderly. The fact that during this period the funding for Dublin City Council and South Dublin County Council increased by 12% and 28% respectively makes these cut backs an even more bitter pill to swallow.

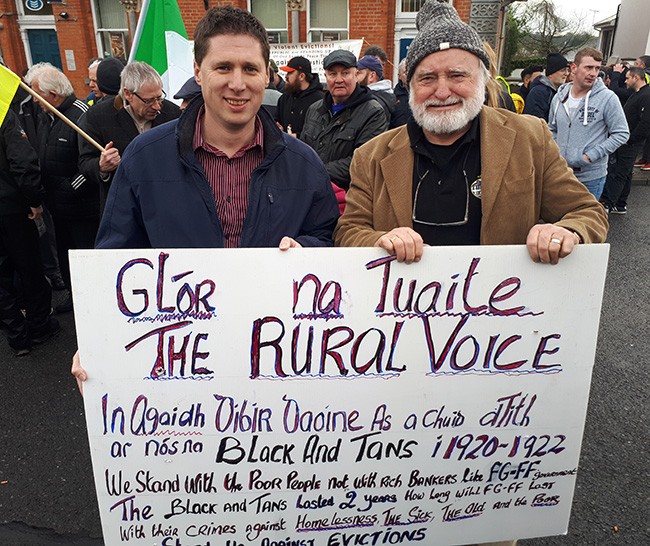

• Sinn Féin MEP Matt Carthy standing up against evictions in Roscommon last December

It’s not just availability of local funding that’s lacking in rural areas, but also local powers. A 2014 study carried out by the University of Lausanne which aimed at measuring the autonomy of local government across Europe found that Ireland had the least. Moldova was second worst. The strongest local authorities were found in Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway.

Theresa Reidy of UCC found in her study of local democracy that Ireland has some of the highest ratios of people to councillors, with one councillor for every 5,000 people. This compares to one councillor per 1,700 people in the Netherlands, one per 1,200 in Denmark, one per 800 in Belgium, and one for every 410 in Finland.

The scrapping of public elections to the board of Údarás na Gaeltachta in 2012 was an undemocratic step that broke the link between that organisation and the public it is responsible to. Established in 1980, Údarás na Gaeltachta is the regional authority responsible for the economic, social and cultural development of the Gaeltacht. There has been an overall cut of 75% in funding to that body since 2008, which tells its own tale.

But people who live and work in rural Ireland don’t need empirical research to know this. The daily lived impact is unmistakeable. When someone in a rural community leaves full time education, it is expected that they will go to Dublin in search of work – but it could just as easily be London, New York, Toronto or Sydney. If their car breaks down, it’s more likely than not that there will be no bus or train to get them to work or school. If an elderly family member needs to get to hospital urgently, there’s no guarantee that an ambulance will come on time. If there’s a serious crime committed in their community, the Garda response will be delayed due to closure of the station in their village.

An innate sense of social and emotional freedom in rural Ireland is also obscured by an official narrative of one-dimensional socially conservative communities.

Historically, rural Ireland has been the backbone of many revolutionary movements and has moulded countless progressive thinkers. Over the past 200 years rural communities have produced some of Ireland’s most radical republican activists and writers such as Michael Davitt, Mairtín Ó Cadhain, Peadar O’Donnell, Liam Ó Flaithearta and Jimmy Gralton.

Today there are many signs of hope for the awakening of rural Ireland to the destructive nature of the economic and political systems in which we live. The mobilisation in support of a farming family brutally evicted from their home in Co Roscommon late last year, the campaign against septic tank charges in 2012, the protests against a ban on domestic turf-cutting and a range of localised campaigns demanding investment in public infrastructure and the retention of local services point to a people aware of the threat faced by their communities and who are prepared to struggle for their survival.

• Local Sinn Féin representatives protesting against evictions in rural Ireland

All of this raises a fundamental challenge for anyone seeking a radical, republican alternative on this island. If the genuine desire exists for a solution to the deepening regional imbalance in this state, this requires a far-reaching and nuanced policy approach not only grounded in a proper understanding of rural communities but offering a practical plan for economic progress in Ireland outside the M50.

We are not short of expert recommendations. Shucksmith and Rønningen have argued, for example, that small farms’ role in rural sustainability should be universally recognised as a progressive, post neoliberal alternative rather than as a pre-modern obstacle to economic efficiency and productivism.

Sinn Féin has continually called for rural proofing legislation. The party’s New Deal for the West plan outlines recommendations such as expansion of the bottom-up co-operative sector; retention and extention of the services provided by An Post; investing in key pieces of infrastructure for the west such as airports, deep-sea ports and upgraded roads; introducing a returning emigrants/diaspora rural resettlement scheme; and the retention in public ownership of all key public service provision so that these are not at the whim of a private enterprise’s profit margins.

The work before us in the battle for survival of rural Ireland is considerable. To bring about these changes is not only to reject the fundamental economic model inherent in any state adhering to the fiscal rules of the European Union, it is to directly contradict the deeply embedded reactionary and conservative forces that have dictated public policy in this state since its inception.

No one should have to ask who the political custodians of Rural Ireland are. Irish republicans and revolutionaries have stood with the downtrodden, the marginalised and the mass of the people against colonialism, and oppression of all kinds throughout history. The battle for survival of Rural Ireland is underway. Let’s not just be on the right side of that struggle, let’s lead it.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures