18 August 2019 Edition

The Northern Crisis as seen from the South

The point of no return – August • 1969 • Lúnasa – Ni raibh aon dul siar as ansin

The 50th anniversary of the crisis of August 1969 should not be seen solely in the context of the Six Counties. This was a crisis that shook all of Ireland and had reverberations among the Irish across the world. It roused public opinion to support Northern nationalists, it both divided and revived the Republican Movement and caused a rift that nearly toppled the Fianna Fáil government.

In theory all political parties in the 26 Counties were opposed to Partition. In practice all governments since 1922 had stopped short of confrontation with the British government on the issue. The first Free State government, that of Cumann na nGaedhal, in 1925 had signed a humiliating agreement with the British that effectively cemented Partition. This was after the Boundary Commission, a key factor in persuading Michael Collins to sign the Treaty, was exposed as a sham. Far from ceding so much territory to the Free State as to make the Northern Ireland state unworkable, as Collins thought it would, the Commission actually proposed to cede Free State territory. Even the virulently anti-Republican ‘Irish Independent’ newspaper said that if such an outcome had been anticipated then Collins and Arthur Griffith would never have signed the Treaty.

This debacle was one of the factors that helped the rise of Fianna Fáil from its founding in 1926 until de Valera led it into government for the first time in 1932. Dev maintained his anti-Partition rhetoric throughout his career and received repeated electoral mandates on that basis. While his critics, both from a Republican and a pro-British point of view, can point out that the rhetoric was not matched by action, the fact remains that successive British governments continued to deny the expressed wish of the majority of the Irish people for a United Ireland.

It is often said that people in the 26 Counties knew little of the realities of the discrimination and second-class citizenship experienced by nationalists in the Orange State. There is some truth in that but that does not mean it was not a political issue. That does not mean it was not raised in public discourse and in diplomatic contacts between the Irish and British governments and wider international opinion – it was. But once again, the action or lack of action of successive Irish governments belied the rhetoric.

Anti-Partition campaigns involving ‘respectable’ politicians in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s were among the influences that led young people to join the reorganised IRA of that period, focussed on a renewed effort to end Partition by an armed campaign along the Border and in the Six Counties. But the response of de Valera, in his last term as Taoiseach in 1957, was to impose internment without trial of Republicans, just as the Orange government in Stormont had done.

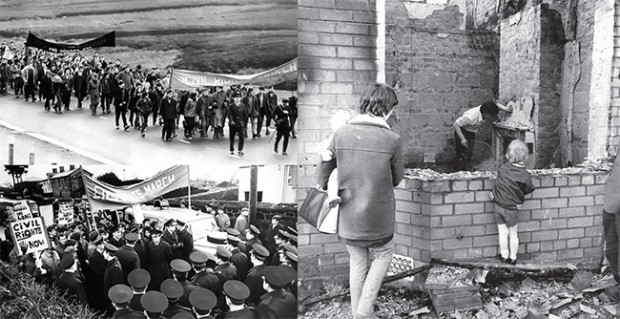

The end of the IRA’s Border campaign in 1962 led to disillusionment and a reassessment of Republican strategy that continued for several years. As part of that re-orientation Republicans were active in the Civil Rights Movement in the North, among people of many different political hues and none. The momentum achieved by that movement did not come from the Republican involvement but from the reality of the Orange state itself, as experienced by nationalists for nearly 50 years. A new generation was ready to challenge the state in an open way that their parents and grand-parents – often simply for reasons of pure survival – had not been able to do.

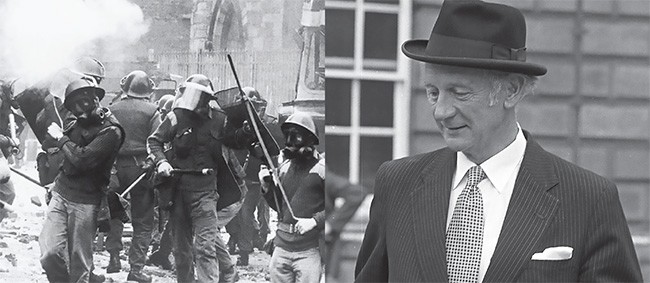

The reaction in the 26 Counties to the Civil Rights Movement was overwhelmingly sympathetic. When RTÉ cameras captured the attack by the RUC on the Civil Rights marchers in Derry on 5 October 1968, the violence of the Orange state was brought into homes in every corner of Ireland. The pattern was repeated in the escalating events of 1969, culminating in August in the Battle of the Bogside in Derry and the pogroms against nationalists in Belfast. The deployment of the British Army on the streets escalated the crisis to a new level.

Responding to public anger, Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Jack Lynch said that the government “could not stand by” and the military were mobilised with ‘field hospitals’ along the Border. Appeals were made openly by nationalists for weapons to defend their communities. Many weapons were sent North by Republicans and by other sympathetic citizens and such was the popular support for nationalists that little was done to impede them.

In fact, behind the scenes, the Lynch government had arranged for the importation of weapons to be transferred to defence committees in the Six Counties. A great deal has been written and a lot more spoken about this ‘Arms Crisis’ but two facts are usually glossed over – the real crisis was that being experienced by the nationalists on the ground in the North and the arms plan was a government one, not the action of a rogue element as Lynch and his supporters tried to pretend. When the Fine Gael opposition was informed of what was happening by top Department of Justice official Peter Berry, there was a scramble to find scapegoats. These included Captain James Kelly who was put on trial.

In 2001 more evidence came to light exonerating Kelly and others. Speaking in a Dáil debate on the revelations, Sinn Féin TD Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin said:

“Deputy [Dessie] O’Malley is not alone in what I regard as the totally false view that what was at issue in 1969 and 1970 was an alleged threat to democracy in this jurisdiction. In this fairy tale version of recent history, the late Jack Lynch saved the people from anarchy and civil war. This grossly partitionist view deliberately ignores the catastrophe experienced by the nationalist people of the Six Counties. People were killed by the B-Specials and the regular RUC in collusion with loyalist paramilitaries. They were forced from their homes, their streets were burned and we had one of the largest forced movements of the civilian population in Ireland, if not since Cromwell then certainly since the Famine. This was the real threat, crisis and catastrophe in Ireland in 1970 and it was not in the leafy suburbs of Dublin 4.

“The problems in 1970 were not what the government did but what it failed to do. It failed to come to the defence of those under attack by the forces of the Orange state. It failed to confront the British government with its responsibilities. The nationalist people saw the prosecution of the defendants in the arms trial as confirmation that the political establishment in the State had abandoned them and was concerned only with its own partitionist political interests.”

If Lynch was stepping back from the Northern crisis this was not the case with public opinion and with many in his own party. A recently published book ‘A Broad Church – the Provisional IRA in the Republic of Ireland 1969-1980’ by Gearóid Ó Faoleán (Merrion Press) dramatically illustrates the level of support for militant Republicanism in the 26 Counties in the period 1969-1972.

The author shows how the British government was incensed by the many acquittals or light sentences for people charged with arms offences and other charges related to the conflict. Examples include the acquittal of a Mayo farmer who had been found in possession of a Thompson gun, rifles and pistols, five County Antrim men in November 1971 fined €20 each for possession of arms, a Derry man found not guilty even though he accepted full responsibility for two hand grenades found in his possession. In most cases these were jury trials and acquittals by juries or light sentences by judges were commonplace.

In an extraordinary indication of his position, Jack Lynch actually named to the British ambassador several judges whom he alleged were overly sympathetic to the IRA, claiming they were ‘bad’ or ‘weak’! This was revealed following the release of British State papers under the 30-year rule.

Public sympathy for Republicans, as manifested by jury verdicts, was the real reason why in May 1972 the aforementioned Dessie O’Malley, Fianna Fáil Minister for Justice, re-introduced the juryless Special Criminal Court to try political cases. O’Malley’s claim that the reason was intimidation of juries was not supported by evidence, even when O’Malley was challenged by the Opposition in the Dáil to produce it.

Of course sympathy was not confined to court cases. Public support was shown in many ways including public demonstrations, financial aid, practical support such as providing safe houses and arms dumps. This ensured that the Provisional IRA which emerged from the split in the Republican Movement in 1969/1970 grew rapidly and could rely on significant support in the 26 Counties. However, the split and the immediate need for defence in the Northern crisis meant that there was a lack of organised civil support, either in an effective Sinn Féin organisation contesting elections and campaigning, or in any significant broad political front. Despite being shaken by the crisis, the two conservative parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, remained totally dominant in the 26 Counties. Writing in ‘The Politics of Irish Freedom’, Gerry Adams says of this period: “The primary problem was lack of politics, a shortcoming which was to remain even after guns had become plentiful.”

The extent of support for Republicanism and its potential, is best demonstrated by the reaction against it by the political establishment in the 26 Counties.

When the British Army committed the Bloody Sunday massacre in January 1972, the Lynch government did little to prevent the burning of the British Embassy in Dublin, seeing it as releasing a pressure valve. But, as mentioned, the Special Criminal Court was soon re-established. RTÉ was whipped into line with Republicans being banned from the airwaves under Section 31 of the Broadcasting Act later in 1972. By the end of that year there were hundreds of Republicans held in Mountjoy Prison and in the Curragh.

A climate of fear was created in which it was alleged that Republicans wanted to ‘bring the war down here’. Playing on this fear, British agents carried out bombings in the 26 Counties, beginning with the Dublin bombs of December 1972 that were designed to spook the Dáil into supporting stronger repressive laws. And they succeeded. This culminated in the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of May 1974, that took 34 lives.

It would be a long time before censorship and repression would be overcome in the 26 Counties and a new era opened up by the Peace Process.

• Mícheál Mac Donncha is a Sinn Féin councillor on Dublin City Council