18 August 2019 Edition

The point of no return

The point of no return – August • 1969 • Lúnasa – Ni raibh aon dul siar as ansin

In Belfast, days later, loyalist mobs took advantage of the IRA’s disorganisation and lack of weaponry to invade Catholic areas, driving people from their homes, burning, and looting. Of all the areas worst affected, Bombay Street, stood out in people’s memories and became the symbol of Belfast’s last pogrom.

In August 1969 the Six Counties erupted in civil unrest and loyalist pogrom as the Orange state came apart at the seams. Nationalists were no longer prepared to endure discrimination and second-class citizenship, and the only answer the statelet had for the demands of its oppressed minority was violence and repression.

Two landmarks stand out in those few brief and turbulent days, which had tremendous consequences for the Orange State, for British rule in the Six Counties, and for republican resistance to both. Free Derry Corner and Bombay Street became synonymous with that period. Free Derry Corner was the spot where nationalists, armed with petrol bombs, stones, and any other missiles that came to hand, took on and defended Free Derry from the RUC.

In Belfast, days later, loyalist mobs took advantage of the IRA’s disorganisation and lack of weaponry to invade Catholic areas, driving people from their homes, burning, and looting. Of all the areas worst affected, Bombay Street, stood out in people’s memories and became the symbol of Belfast’s last pogrom.

The following series of interviews by An Phoblacht’s LAURA FRIEL (first published in 1999) tells of that critical period in Belfast’s troubled history, a moment which brought British soldiers onto the streets and set the scene for the long war ahead.

• Rita Canavan pictured in 1999

RITA CANAVAN

“We lost everything but our sense of humour,” says Rita Canavan. In a photograph taken in August 1969, two small boys are standing outside the burnt out facade of what had been the Canavan family’s Bombay Street home. Short trousers, spindly legs and cropped hair, one child stands up straight for the camera, but his face seems pensive, anxious, unsure. His companion, hands on hips, strikes a more defiant pose.

Behind them, a row of modest terrace houses, fire gutted, roofless, without doors or windows, stand in silent testimony to the sectarian hatred in which they had been engulfed. It’s a simple snapshot but all the elements are there, fear and defiance, vulnerability and courage. For the last 30 years, the image of Bombay Street has haunted not only the memory of residents whose homes were destroyed but the Northern nationalist psyche. And not without reason. Between 1969 to 1973, it is estimated that 60,000 Catholics in the Six Counties were driven from their homes.

As newlyweds, James and Rita Canavan moved into Bombay Street in the early ‘50s.

Rita remembers the area as a “quiet community of decent hardworking people.” The largest factory, Mackies, despite being located in a predominantly Catholic area of West Belfast, drew its workforce almost exclusively from the Protestant community, the vast majority from the Shankill. Catholics were more likely to be employed in unskilled, low paid jobs, as store keepers in warehouses, in the mills and at the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Whenever there was trouble brewing, Catholic families lived in fear of Mackies’ afternoon shift finishing before the local men, forced to work outside the area, had returned home. When on Friday 15 August, 1969, hostile loyalist crowds began to gather for a second evening running, “there was an insufficient number of men to defend the area,” says Rita. “Some women wanted to put up barricades but we were persuaded that everything would be alright by a local priest who was in contact with members of the Protestant community.”

Outside a shoe shop on Cupar Street, members of the RUC and B Specials were standing with a crowd of loyalists. “We thought the RUC were there to stop the loyalists invading the area,” says Rita. “We were wrong, they gave us no protection at all.” As fears of a loyalist incursion increased, the decision was taken to evacuate Bombay Street and a number of vulnerable streets in the surrounding area. “Crates of petrol bombs had been seen by one of my neighbours.” Residents boarded up windows and barred their front doors. “Mrs McCarthy and I were the last two in the street to leave,” says Rita.

St Paul’s parish hall was overflowing with refugees. “There were people there from Ardoyne and other areas of Belfast where Catholics were being attacked,” says Rita. Despite the noise and smell of burning, the refugees at the parish hall did not anticipate the scale of the destruction which would greet them the following morning. “A priest told everyone to go home except those families from Bombay Street,” says Rita. “We thought the house had been looted, we never imagined the whole street had been burnt to the ground. There was nothing to salvage. All we had were the clothes we stood up in.”

With four young children and expecting a fifth, Rita and her family stayed with relatives until they were allocated a caravan in Beechmount. “It was like a refugee camp,” says Rita. “We stayed there throughout the winter of ‘69. It was so cold even the toothpaste froze in the tube.” But as well as the hardship, Rita remembers a sense of community and individual acts of kindness with affection and praise.

The young men who held loyalist gangs at bay while their families saved what they could, “they were heroes,” says Rita. The Travelling community who faced loyalist violence to collect the furniture of fleeing Catholic families in their lorries, “they were great,” says Rita. And the many thousands of people who contributed time and money to rebuild Bombay Street are also remembered. “I moved back into Bombay Street on 11 July 1970,” says Rita, “and I’ve lived here ever since.”

• Nellie McAuley with Tom Hartley, Easter 2009

NELLIE McAULEY

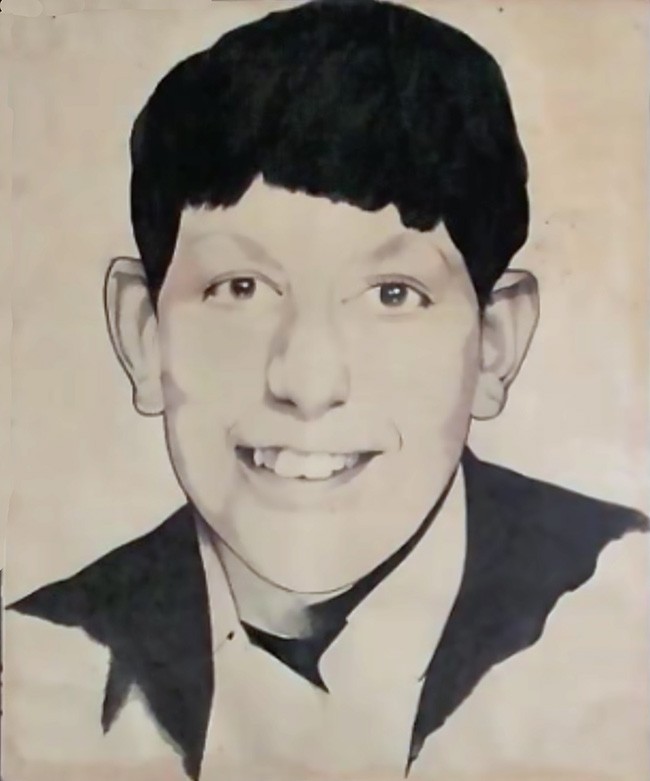

“He’s not coming home,” says Nellie McAuley. “They were the words that confirmed my worst fears.” A large black and white pen portrait of her son hangs in the living room of Nellie’s terrace street home. “It was drawn by one of the prisoners in Long Kesh,” says Nellie, “and given to Gerald’s uncle. It’s a good likeness.”

Gerald McAuley was 15-years-old when he was shot dead while defending the Clonard district from loyalist attack. The likeness shows all the optimism and confidence of youth. The kind of face which should have been more at home on a GAA pitch challenging his peers, than facing a pitched battle against a rampaging Orange mob.

At 7am on Friday 15 August, Nellie was in Belfast city centre where she was working as a cleaner in one of the big stores. “I was working when I heard the news that a wee boy, Patrick Rooney, had been shot dead by the RUC in Divis Flats the night before,” says Nellie.

There were no buses for the return journey home. “A young woman was standing at the bus stop in the town,” says Nellie. She was a Protestant, the girl told Nellie, and was too afraid to walk home through West Belfast. “I told her she’d be alright with me, and we linked arms and walked home together.”

Years later, the two women met again. “She remembered me and also knew that my son had been shot dead just hours after we first met,” says Nellie. She thanked Nellie for her kindness and said she had been sorry to hear Gerald had been killed. “It was ironic,” she said. “No, it was tragic,” said Nellie.

“I’d been out queuing for bread,” says Nellie, “and when I returned home there was a commotion at the house. Someone said Gerald had been shot. Another neighbour said he’d only been hit with a stone.” With an increasing sense of foreboding, Nellie began a desperate search for her son.

• Portrait of Gerald McAuley

“I heard some of the wounded had been taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital. I pleaded with a nurse to let me search the wards.” A neighbour waiting in Casualty for his injuries to be treated confirmed that Gerald had been shot but he wasn’t at the Royal.

Back at home, news reporters had visited the McAuleys, asking for a photograph of Gerald. “He must be dead,” Nellie told her daughter Frances. Finbar McKenna’s father took Nellie to the City Hospital. “A sister at the hospital said Gerald wasn’t there but there was a 19-year-old youth in the morgue at Musgrave Barracks,” says Nellie. “I knew it was Gerald; he was only 15 but he was big for his age.”

Returning home, the reaction of people manning a barricade at Kennedy Way added to Nellie McAuley’s fears. “They moved so quickly and quietly out of our way.” From across a road a priest called to Nellie. “Are you looking for your son?” said the priest, “He’s not coming home, go home now, he died for his faith.” Later that night Gerald’s father travelled to Musgrave to identify his son’s body.

“I didn’t know Gerald was a member of the Fianna,” says Nellie. “He was often away from home cycling and camping but I never thought anything of it. I was told later that he had been helping evacuate families, loading their furniture onto the back of a lorry.”

The McAuley family’s ordeal did not end there. Three weeks later a British army captain knocked on their front door. “He asked for my husband and told him he was wanted down the barracks to identity his son,” says Nellie. “My husband told him Gerald was dead and buried but he insisted. ‘Is it Jim?’ he asked. At the barracks the RUC roared with laughter. It was their idea of a joke, a sort of initiation stunt for the British Army officer.”

• Sammy and Ann McLarnon

ANN McLARNON

“My husband was murdered for being a good neighbour,” says Ann McLarnon. In the front parlour of the McLarnon family’s Ardoyne home, Ann recounts the night when as a young wife she was robbed of a gentle husband and her three small children lost a father they were too young to really know.

On the wall hangs a small snapshot of a happy couple on their wedding day, holding hands as they walk together down a terraced street. Above the television hangs a much larger framed newspaper cutting of Sammy McLarnon’s funeral cortege.

As Ann tells her story, her voice is trembling and there are tears in her eyes. If Sammy and his bride’s joy had been brief, the grief of his widow has been as long as the trailing line of grim-faced mourners carrying Sammy’s coffin along a winding road.

“We heard shooting earlier that night but I didn’t know what shooting was and when Sammy dismissed it as only blanks I was reassured,” says Ann. “Sammy wanted me and the kids to go and stay in his mother’s house but I refused.”

Ann and Sammy moved into Herbert Street shortly after they were married. By August 1969 the young couple had a two-year-old son, Sammy, a baby daughter, Ann Marie and Ann was expecting their third child, Samantha. Ann was only 20-years-old, her husband just 27.

At the top of the street, a crowd of loyalists had gathered together with some members of the RUC. “A house had been set on fire,” says Ann, “and Sammy went up to help put out the flames.” Shots were fired as a few local residents tried to save the house. “Leave the fenian bastards to us,” an RUC officer had shouted to the loyalist mob.

“When Sammy came back into the house we both stood by the front window watching two fellas standing directly across the road,” says Ann. “The RUC spoke to the two men and they were moved away.” Ann went out into the kitchen.

It was only a few moments later. “As I walked back into the front room, three shots rang out,” says Ann, “Sammy fell to the ground.” Ann remembers calling her husband’s name, screaming and running for help next door.

Sammy McLarnon’s body lay where he fell for over five hours while the RUC and B Specials refused to let an ambulance through to the house. In the end, the dead man was taken away in a black taxi. Ann and her children were taken to Sammy’s mother’s house in Andersonstown. “I was in a state of shock,” says Ann. “I couldn’t think. I didn’t want to believe Sammy was dead.”

Later on the night of the killing, the RUC opened fire again on the McLarnon family’s home. The walls of the house were riddled with gunfire. It was over a month later before the RUC sent a forensic team to investigate the crime scene.

“There was only three shots fired when Sammy was killed,” says Ann. “I have no doubt that those shots were aimed. The RUC deliberately killed my husband and then covered it up. The house was riddled so that it seemed as if Sammy had been killed by a stray bullet, an accident.”