18 August 2019 Edition

1969 was a popular uprising

The point of no return – August • 1969 • Lúnasa – Ni raibh aon dul siar as ansin

In the affairs of life there is always a ‘defining’ point where transformation begins; it can be a year, a moment, an event or a series of events but fundamental change is invariably the outcome.

In my case the year was 1970, June 27th to be exact. The location, Short Strand/Ballymacarrett; and to be even more accurate, time wise, between 9pm and 3am.

Local history records the experience as ‘The Battle of St Matthews’ and broader history records it as the rebirth of the modern IRA.

Unionist paramilitaries with the connivance of the British Crown forces laid armed siege to the Short Strand from several points around the perimeter of the district. A six-hour gun battle raged with several people dying and being injured and many premises looted and burnt out by rampaging unionist mobs.

I was baby-sitting with a friend of mine and as events conspired, as a 16-year-old, I was an eye-witness to such epic-making hours.

I was not an eye-witness to the ‘defining’ moment which was the beginning of the end for the northern state, which took place the previous year, 1969, some few miles away from the Short Strand on streets similar to the streets that I witnessed, albeit unknown to me, the rebirth of the modern IRA.

The infamous burning and sacking of Bombay Street, in the mid-Falls and the less infamous but nonetheless deadly attack on the nationalist people of Ardoyne in north Belfast and Derry’s Battle of the Bogside sounded the death-knell for the Official Unionist Party, OUP, which ran the one-party unionist state.

Within a few years the OUP had lost its vice-like grip on the state as it reeled from one crisis to another – a crisis engendered primarily by its military response to what essentially was a political crisis.

It took a longer time to end the actual existence of the one-party unionist state but the 1969 pogrom and the Battle of the Bogside sowed the seeds of the state’s formal collapse – some thirty years later in 1998, when the Good Friday Agreement ushered in a new all-Ireland framework wherein a recast northern executive and assembly functioned as part of a new all-Ireland entity.

The burning of Bombay Street and the attack on Ardoyne by unionist mobs, with the approval of the state’s political masters, and the uprising in the Bogside, triggered a series of events designed to stabilise the state but in actual fact deepened the crisis.

The context for the popular uprising from 1968 onwards was the Civil Rights Movement of the mid to late 1960s which led a popular reform campaign focused on housing and voting rights.

The inability of the unionist government to positively reform the system of government fanned the opposition within the north’s population, especially the nationalist people, who were on the receiving end of a comprehensive system of discrimination which deprived them of political and economic power and reduced them to the margins of life, irrespective of their class background.

The violent reaction of the unionist state to the modest demands of the Civil Rights Movement confirmed for republicans, their long-held belief, that the northern state could not be reformed and that partition and Britain’s occupation of the north was the fundamental problem.

The popular uprising by the nationalist people of the north in 1969 emboldened republicans, in particular the IRA, to reorganise and prepare itself for a war to reunite the country and undo the 1921 Treaty which partitioned the island.

And while the IRA was busy at what it did best, arming, training and recruiting the nationalist people were also discovering a strength they never knew they had.

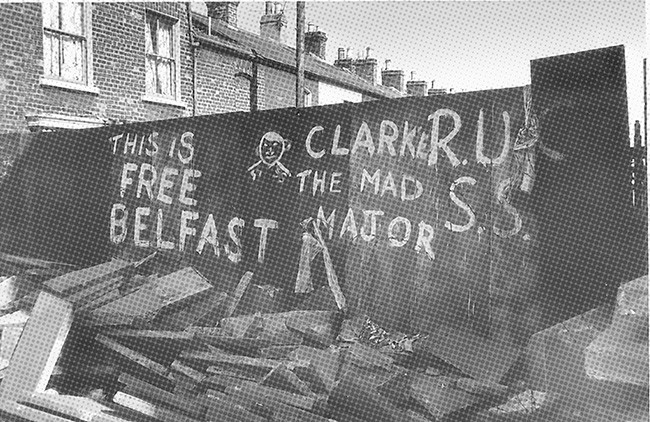

It was a strength that emerged from the streets of the north where students and ordinary people were involved in sit down protests in the middle of busy streets in Belfast city centre, or on civil rights marches like the one from Belfast to Derry, or in occupation of houses, or rioting on the streets.

From partition in 1921 until 1969 the unionist government had ruthlessly suppressed several IRA campaigns – which had limited impact on the stability of the unionist regime.

The big difference the unionist government faced was that from 1969 it was confronted with a popular uprising across the north, which involved all shades and classes of nationalist opinion with a broad range of demands from civil to national rights and all in between.

Its response was the traditional one of military coercion and repression to intimidate the protestors and scare them off the streets.

But it had underestimated the mood of the militancy and determination of the generation who joined in the civil rights marches – or related protest activities.

The nationalist community had discovered a strength and determination in numbers; they had witnessed their own power and they knew they had an influence which could bring about immediate and beneficial change.

They also knew that the unionist system was collapsing under the pressure of the street protests.

And they were determined not to yield until the fundamental change they sought was achieved.

Against this background the unionist government slowly but inexorably moved to the cliff edge and after the Bloody Sunday massacre it tipped over into the political abyss and the one-party sectarian unionist state was gone forever.

• Jim Gibney is a Republican activist, former political prisoner and parliamentary adviser to Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile